We’ve just had the biggest psychological and military defeat in the west since the storming of the US embassy in Tehran in 1979 and the ignominious rooftop helicopter scramble evacuation from Saigon in ’75. Afghanistan’s innumerable victories over the would-be conquering superpowers and their civilising crusades of the last two hundred years demonstrate the truth of Aldous Huxley’s adage ‘That men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most important of all the lessons of history’. We have learnt nothing from the corpses piled high on both sides. We are doomed to keep on making the same mistakes. You cannot bomb a people into obedience.

And yet we find war fascinating. I have always been obsessed with the Vietnam War – or the American War if you are Vietnamese. It was the motif that ran through all of my university days.

LZ

I love the smell of napalm in the morning

The ride of the Valkyrie

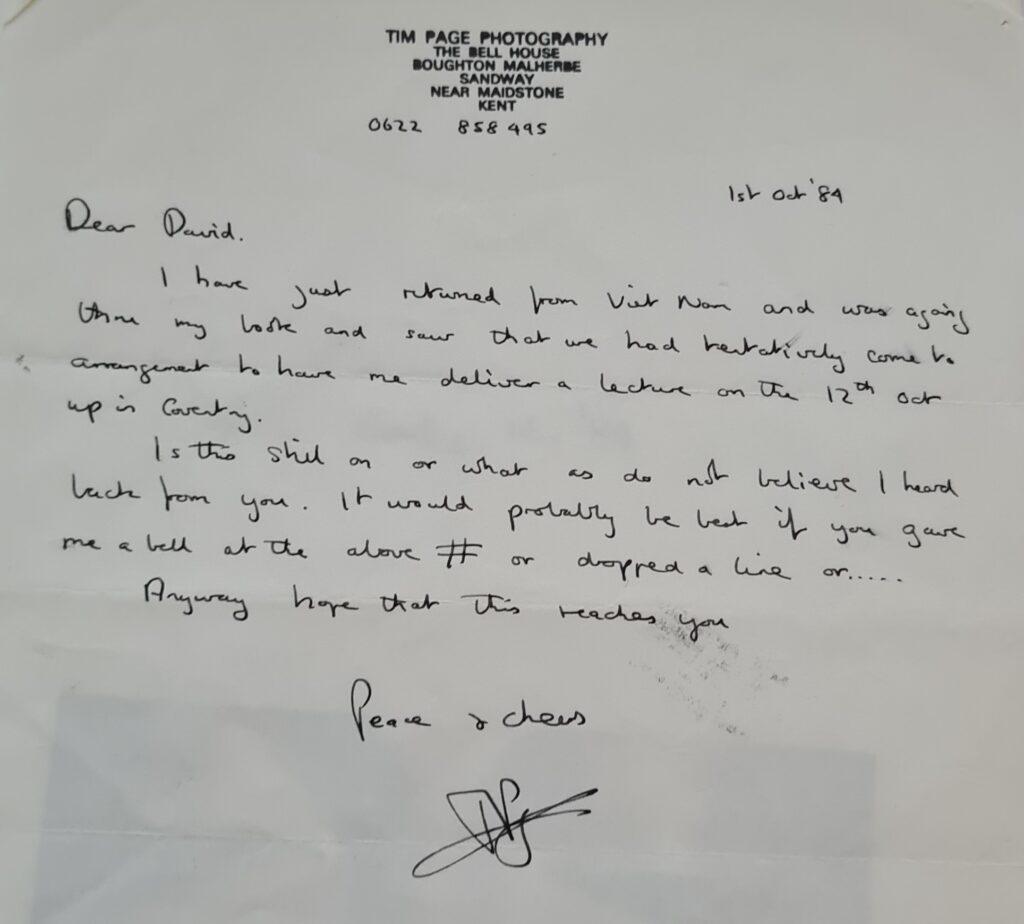

From group viewings of Apocalypse Now with my equally obsessed friends (we knew every line of dialogue and narration and quoted them liberally), through the emulation of the infamous Huey assault on the village by Colonel Kilgore’s ninth Airborne Cavalry as we made a dawn raid, armed with baseball bats, on the students who had taken on the lease of our old property in Leamington Spa to scare them into paying the arrears on the VCR they had inherited but which we were still paying for (we got the wrong people and skulked away with our tails between our legs as they hurled abuse at us – so not really the ‘we come in out of the sun’ guns blazing dawn raid we envisaged); Easter cards themed on helicopter gunship photos, to inviting the legendary war photographer Tim Page (played by Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse) to speak to an adoring crowd of aficionados. (He slept on my floor. It was hallowed ground from then on.)

My autographed copy

Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now – character based on Page

‘Cancel my driving test, I’m going to Vietnam’ Tim Page note to his parents aged 17

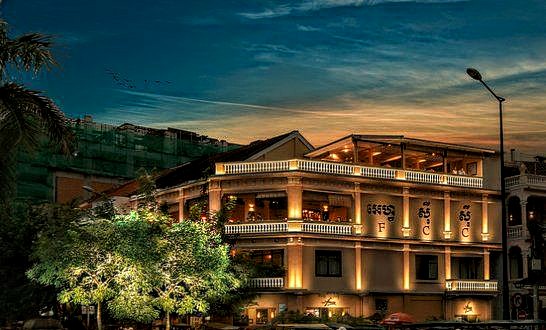

Correspondents club in Pnom Penh, Cambodia

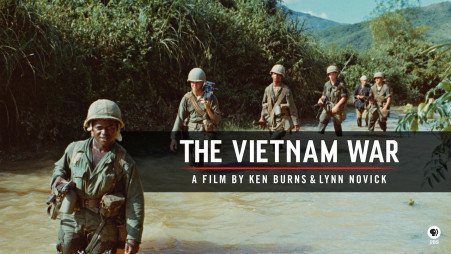

I consumed catalogues of programmes, documentaries, films, libraries of books, biographies and photos of the Nam conflict voraciously and my hunger for more was insatiable. To me it was the everything war: it had horror and glamour and fear and love and drugs and sex and rock n’ roll and stupidity and dark humour and Hendrix and Hueys, double-speak, slang, exoticism, danger, terror. It had allure and I was drawn. But most of all, it had excess. Excess of everything. It was the crucible in which all the hardware of destruction was pitted against the will of a people to be left alone. It was Cold War real politik. It was pitiless on all sides. It was Graham Greene’s The Quiet American – the greatest novel I have ever read – sinister as a stiletto to the ribs and deadly as Hell. It was futile and a lost cause and an act played out by politicians in over their heads with the Vietnamese populace paying the price for a dumb doctrine about dominoes. It was typewritten copy smashed out on sweat-stained, tissue-thin airmail paper that journalists use in the tropics. It was war correspondents gathering in Hemingway-esque bars to shoot beer bottles in a Kalashnikov clay pigeon orgy of violence, booze, adrenalin amusement and lethal, numbing self-distraction.

A Netflix masterpiece

Adrian Kronauer

So you can imagine my excitement when the tops of the palm trees were on a level with our Boeing 747 as it came into land at Ho Chi Minh City airport. This visit had been a long time coming. I knew more about Vietnam than was healthy but I had never been there. My sister Wendy’s sixtieth birthday furnished the opportunity and I leapt. My son Josh joined me and as we came into land I pointed out the window at the adventure below. Eighty million people with the scars to prove a hundred years of consequence for wanting to be left alone by other people who won’t leave them be. It felt like coming home.

Love and light

The sand dunes near Mui Ne

NVA tank and GI Josh

Lauren & Alex in Joe’s Cafe

We had fourteen days and we mixed it up. A bit of beach on the island of Con S’on, the crazy frentic bustle of what I still call Saigon, the sand dunes at Vo Nguyen Giap, Joe’s Cafe at Mui Ne, ornate coach buses, mopeds, night clubs, milk shakes, rip off taxi rides and, oh, that heavenly Vietnamese coffee. But the last morning before we left was mine.

Best coffee in the world

Phô

Storming of the palace

Delta David

You weren’t there, man. Carrying the wounded downstream

Sand surfing the dunes

Sunset Hill overlooking Mui Ne

Banana milkshakes

7th Cav – ‘born to ride’

I had picked out the Lonely Planet Guide City walk of old Saigon and at 5am I hit the war trail. The Majestic Hotel, requisitioned by the Japanese in WWII; the former Brodard Cafe on 151 Rue Catinat (now Dong Khoi), Saigon’s most famous street and immortalised in Greene’s aforementioned novel when he was a war correspondent for The Times in Vietnam before it all escalated. The Caravelle Hotel, where all the foreign news bureaux were based and the hangout for all the correspondents. And the Continental Hotel, another hangout for the press corps, especially during the French colonial war. Another location made famous by Greene. The statue of Ho Chi Minh himself, the incongruous cathedral of Notre Dame and the grand Central Post Office building. It was a delight to walk as the sun came up on another scalding and humid day, its glow reflected off the Saigon River. I felt Greene’s hand on the landscape and the vivid sense of a thousand impressions from my imagination all come to life. Those two hours wandering alone through the history books were my reverential pilgrimage.

Ho Chi Minh

Bombing into the stone age

The horror

The greatest novel about Vietnam

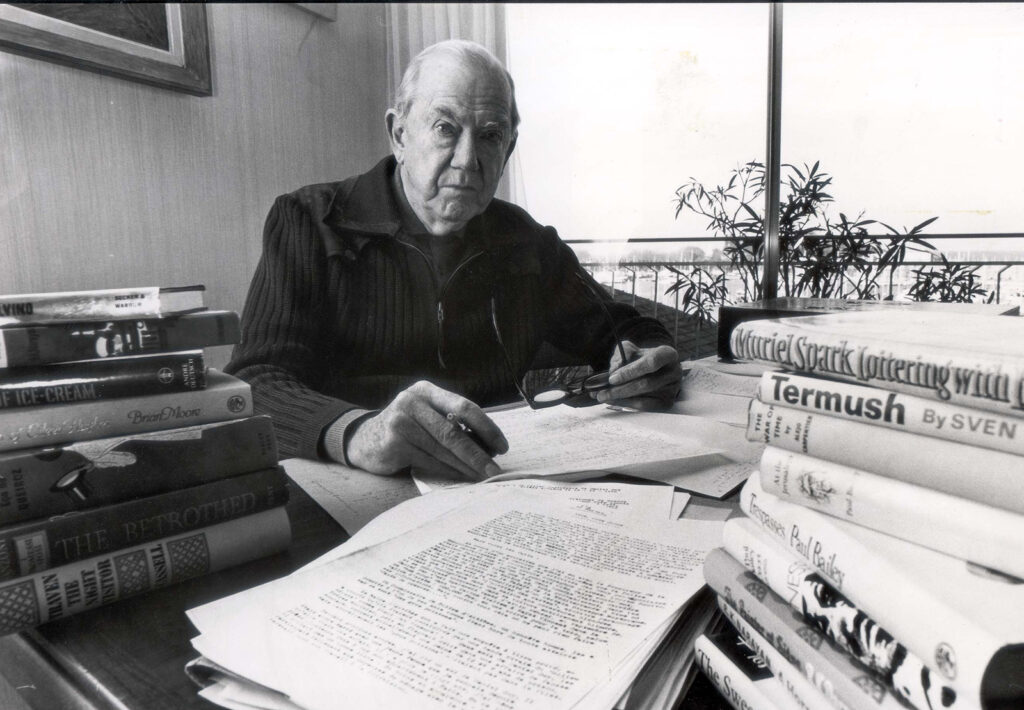

Graham Greene 1951-54 French Indo-China correspondent for The Times

Correspondents’ hangout, Saigon

Graham Greene’s apartment

Sunrise over the river Saigon

Notre Dame

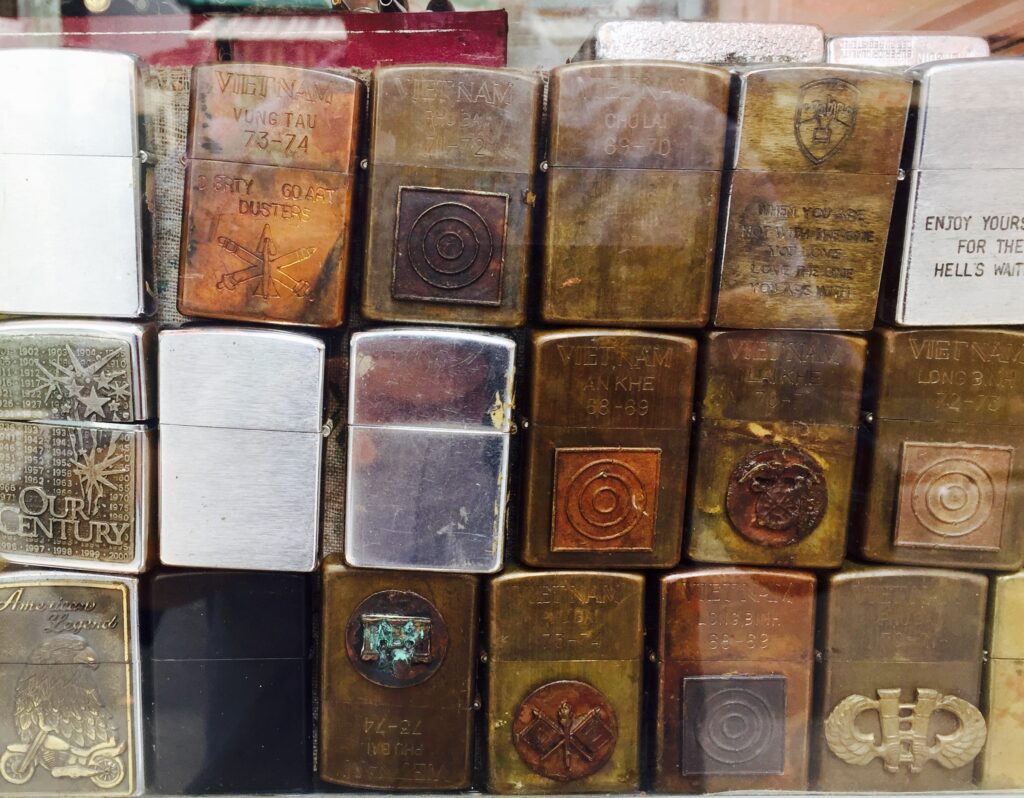

GI Zippo cynicism

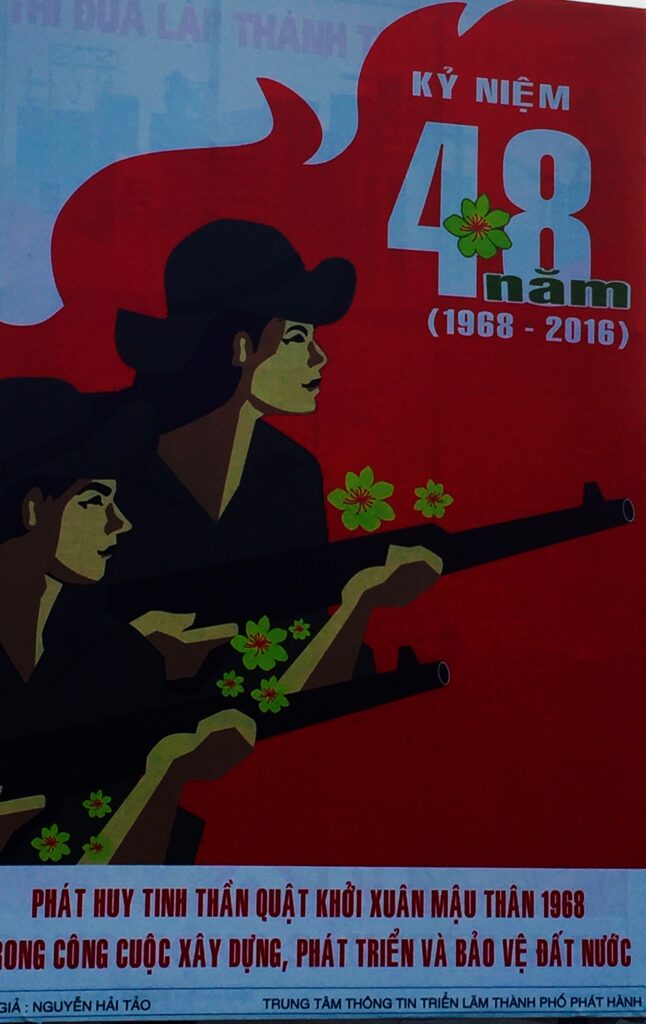

Propaganda poster

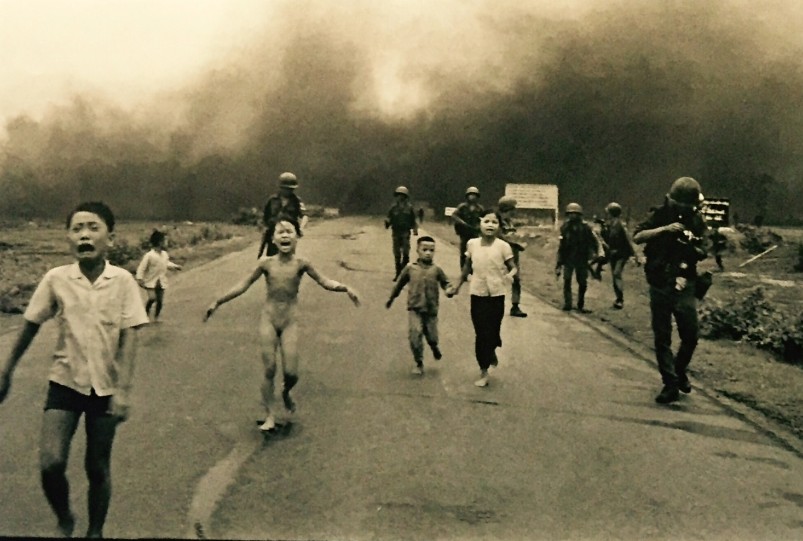

Death, destruction, damnation – democracy delivered from the Delta to the DMZ

I remember saying that if I could choose any war to be in then it would have been this one. “That’s a fucking silly thing to say”, my father spat, “it was a fatuous war”. Spoken like the true rationalist that he was. He never did see the mystique, the celluloid drama it excited in a whole late baby boomer generation. Its farcical, fatuous, nihilistic, tragic nature is what makes it such a draw. It wasn’t a simple war of good versus evil, as WWII had been; it was asymmetric, politically motivated, indefensible – we had no moral force and no place being there. Does that mean I condone the violence? No. Unequivocally not. Walking around the War Remnants Museum and seeing Josh’s education about the war happening live and in full technicolour horror as photo after photo laid bare the viciousness and suffering of agent orange, napalm attack, torture, jungle ambush and a thousand other barbarisms sobered any wish to participate as a combatant. It was a wrong war.

Josh – a year older than the average 19 year old conscript GI

The best coffee in the world

Chi Wendy

But therein lies its appeal. It was the first war fought on television and beamed almost live into the living rooms of America. So to have reported it was a unique moment, the moment when the war correspondent really came of age. And it is that that attracts. To write and bear witness to calamity on such a scale and be the world’s eyes so politicians can be judged in the glare of daylight, that is a job. Those brave souls in Kabul over these last two weeks who flew in to cover the aftermath of US capitulation (and are still there as the last US forces left today) are worthy inheritors of the mantle of their forebears in Vietnam. And, yet again, America and Britain have been caught on camera in another murderously futile enterprise and perpetrating a betrayal few will ever forgive. And, just to leave on an even worse note, the so called precision air strike on the perpetrators of last week’s suicide bomb attack carried out two days ago actualky killed four children. If, and I hope we don’t, we go marching in to any other country to ‘save it’, locals beware: think twice before offering to help us. Because we will leave you behind when we leave. I hope we have more humility next time. But I know we won’t, so the Vietnam War will go on and on and on in perpetuity, just in a different location.