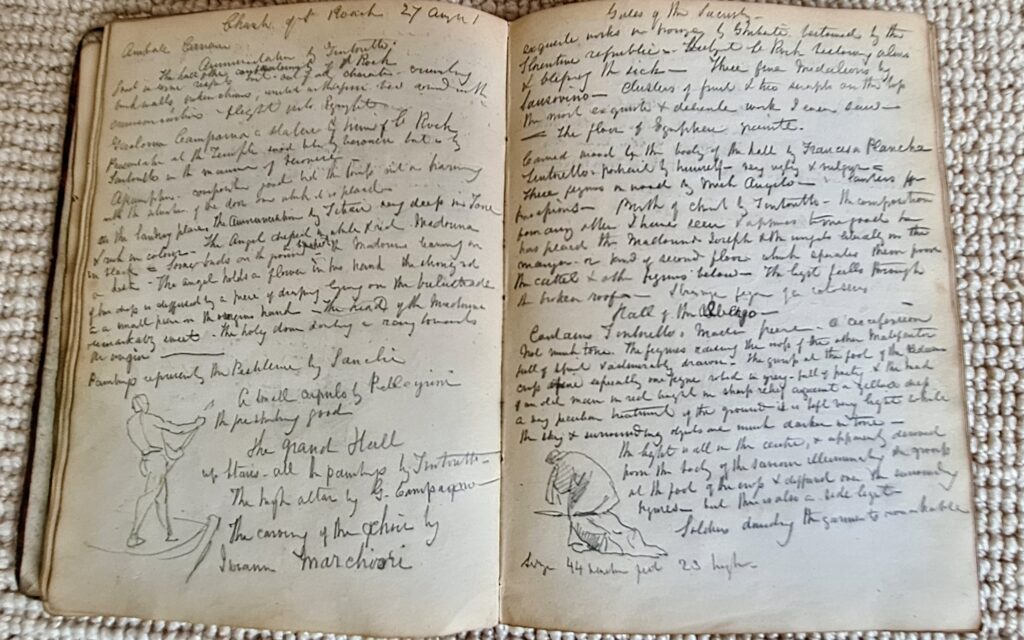

When my grandmother died, my mother and I cleared out her flat. I made straight for the bookshelves. In amongst the volumes of H.G Wells’ History of the World and Winston Churchill’s The Second World War I found one book unlike all the others. The book was not printed. It was a journal and dated 1796. In it were designs, intricate diagrams and copperplate pencil writing detailing stage sets and costumes. It smacked of significance. I was hooked. This discovery ignited my fascination with notebooks and supercharged a life long love affair with the written word, especially the handwritten word.

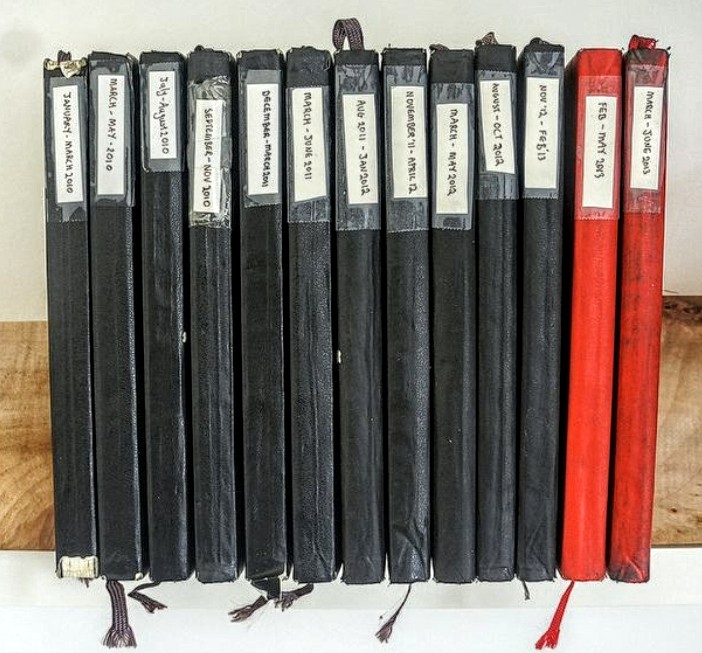

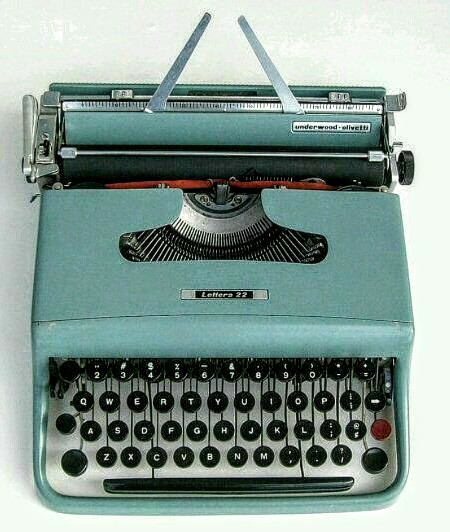

Handwritten or typed on my Lettera 22, my diaries and journals accumulate on our bookshelves, each one a complete world. Some light, some dark. Adventures, travels and times with my children, family and friends rub shoulders with thoughts, feelings, opinions and passions. And all of them are collected in a wide and beautiful array of volumes: scrapbooks, journals and books.

You are never alone with your notebook

I remember one evening at La Terrasse, a Parisian rooftop restaurant in the Quartier Pigalle, spending the whole evening writing. The food and wine came and went almost unnoticed, and the chatter of my fellow diners created a background atmosphere to complement the warm summer night, the lights strung out across the terrace and the bustle of the waiters. The conversation subsided as the guests left table by table – I was oblivious. I was in my reverie, in the company of my thoughts, a pen and my notebook. It was one of the happiest nights of my life and confirmed that I wanted to earn my living by writing.

La Terrasse, Paris

The compulsion to write everything down, collect, collate and curate my own existence caters for another very real compulsion. I am a stationery addict. I admit it. I even collect friends that are as addicted as I am. Even in the modern era of laptops and smart phones, of being able to write anywhere and everywhere and have it captured instantly and forever via social media, there is something wonderful and tactile about a notebook or a journal that cannot be replaced by bits and bytes. Notebooks are alive. Organic. Permanent. The act of writing in them and filling them up is a commitment to a point of view; a commitment to testimony. To hold them, caress them, flick through their pages and alight upon one passage or illustration or photo at random is magical. Like being let in on a secret world. That world might be profane or sacred, full of love or remorse; it might be revelatory or arcane or prosaic. It doesn’t matter. A well-filled notebook is a house full of thought, ambition, despair, longing, hope – it is furnished with insight and remembrances. In each room there are smiles of recognition of half forgotten moments, observation, self-reflection, accounts of conversations. Notebooks are as fun to flick through and read as they are to write. There is an aesthetic as well as an intellectual irresistibility about a filled up notebook, dog-eared and worn from usage. They are evidence of existence, as incriminating as they are valedictory. And as the years progress and memory fades, they are how we remind ourselves of how life was and how it felt to be back then.

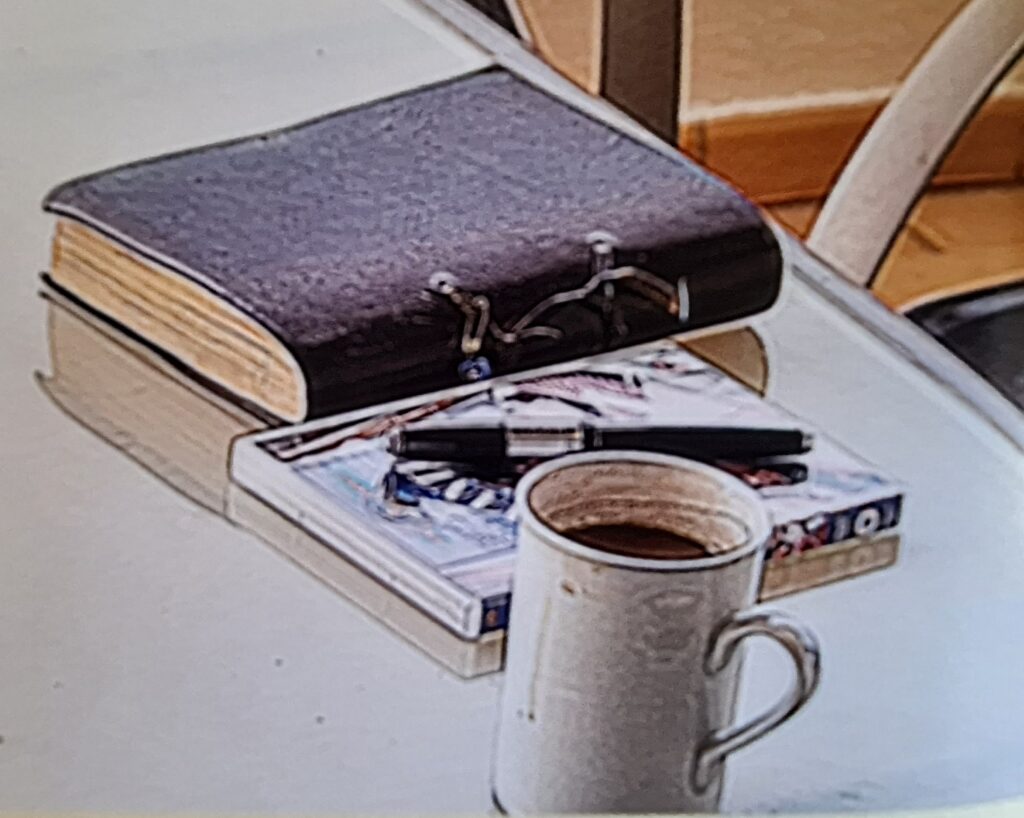

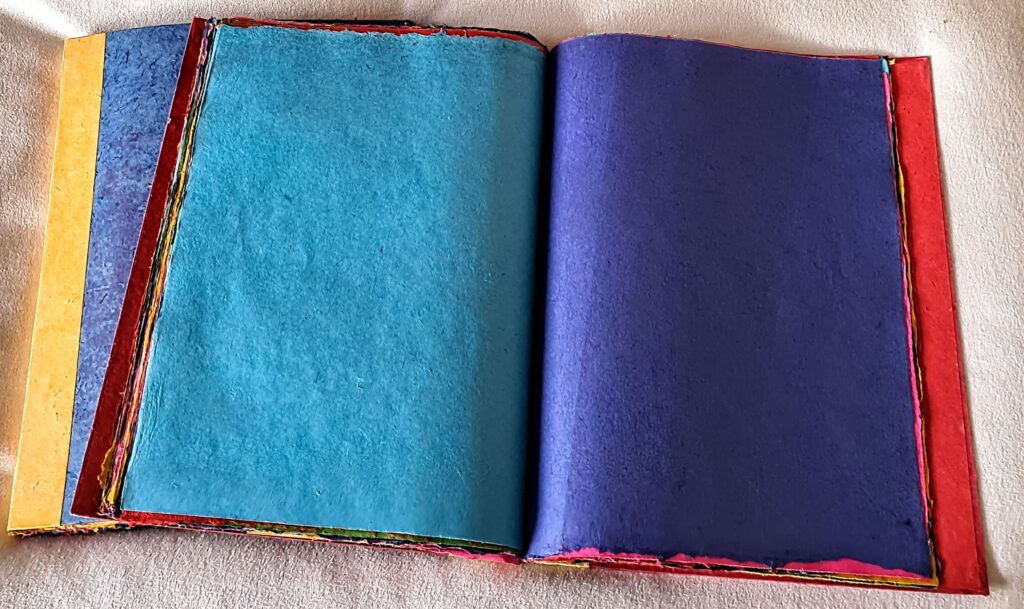

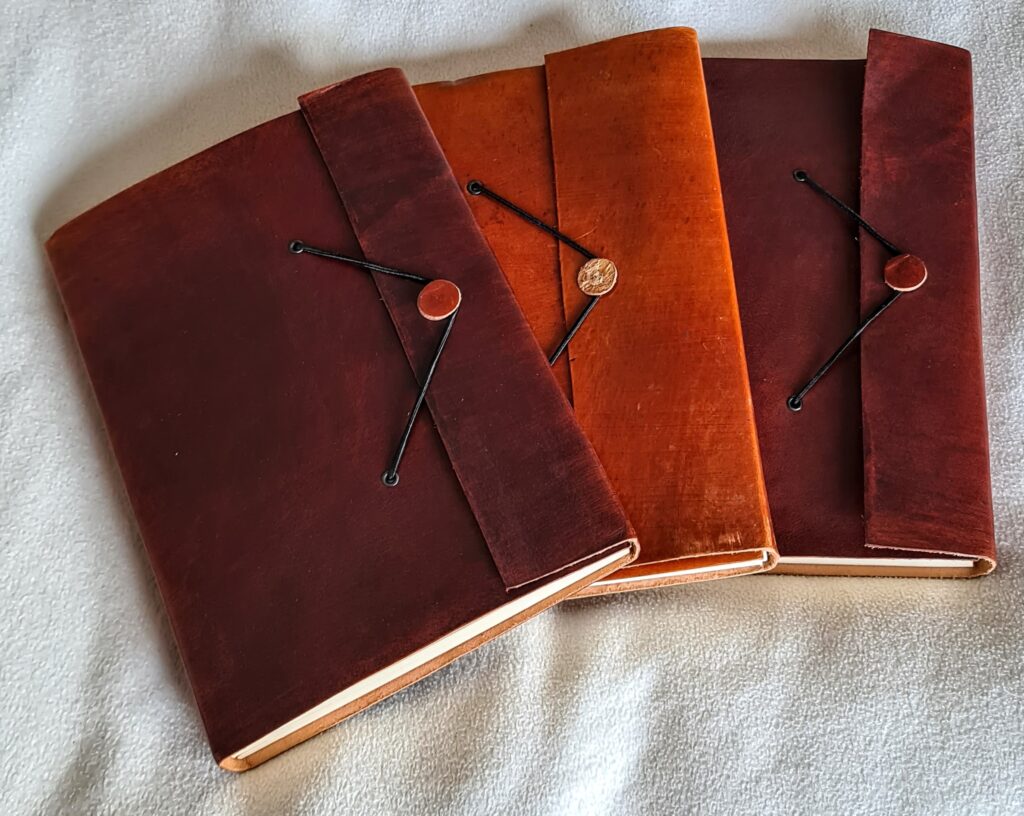

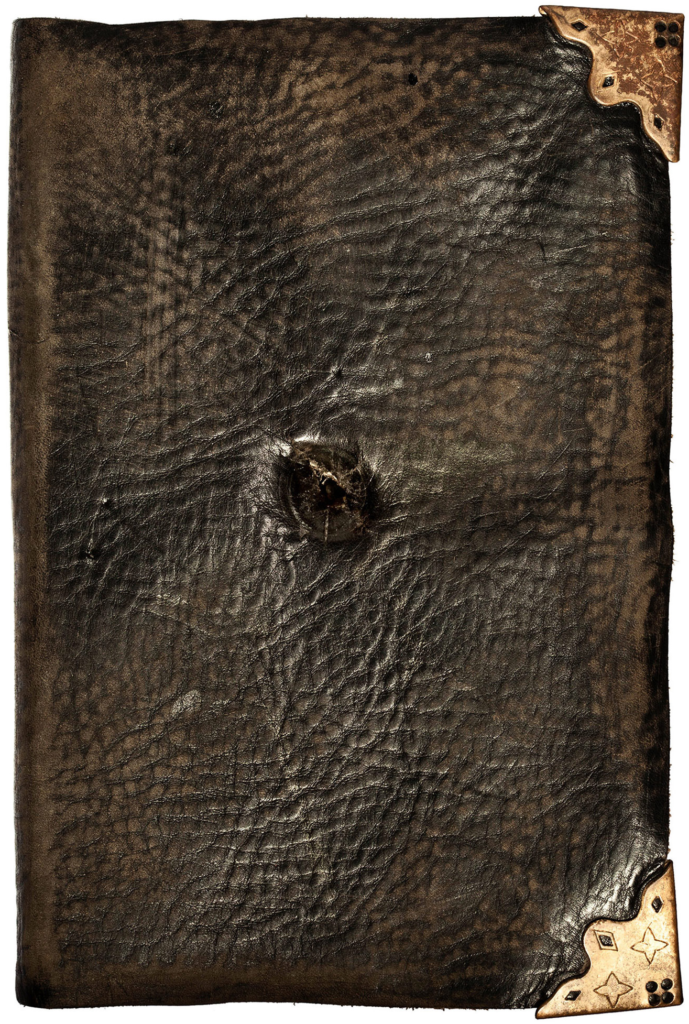

The paraphernalia of the written word – ink, fountain pen, pencil, paper and notebook – are part of my identity as a writer and human being. I have lugged box loads of Moleskine’s, scrap books and my collection of leather bound journals from house to house over the years – only a portion of which have been filled. The rest are there because they caught my eye on some market stall or other, or in a shop; because they would come in useful one day, because they fitted into some imaginary plan I had to write about this or keep notes on that. Green ostrich skin for my travels down the European Atlantic coast; four sizeable Indian journals bought in Pollença for my life journals. One very large format inlaid black leather volume for a journey to Morocco when we can travel again. Plus a plethora of decorative books, bejewelled and inlaid with gemstones and their black, plain, Puritan Moselskine cousins. All just waiting for the right opportunity to fill.

Moroccan leather large scale for large adventures in off the beaten track places

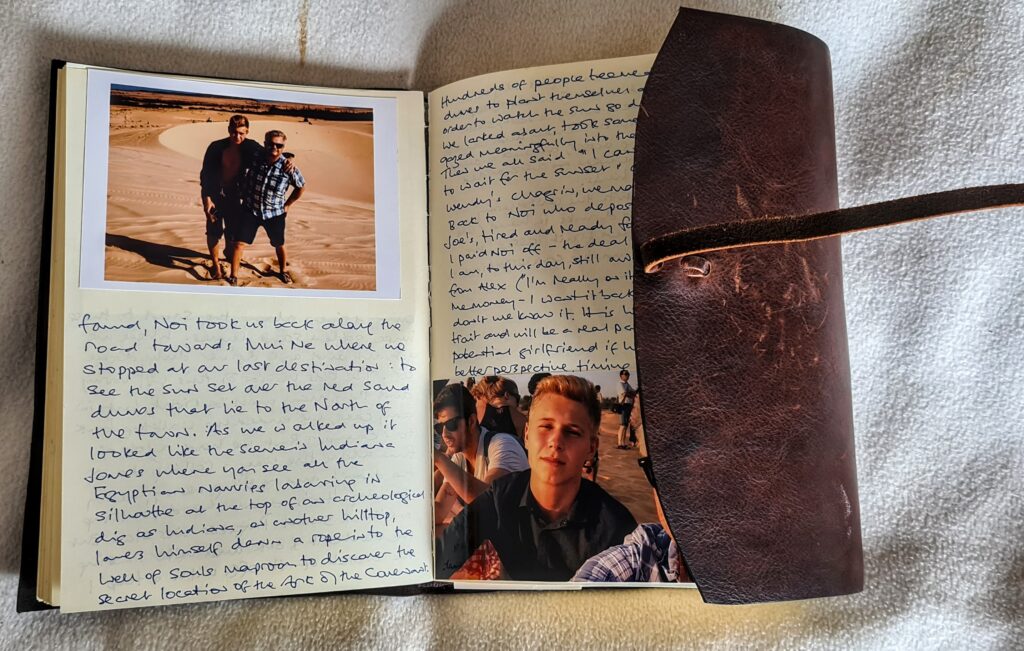

My holiday journal accompanies us to all points of the compass

Very early morning works best for me

Scrap books from the Conran Shop

Hand made Nepalese paper

Supersize portfolios for documenting family life

Life journals – leather bound luxury

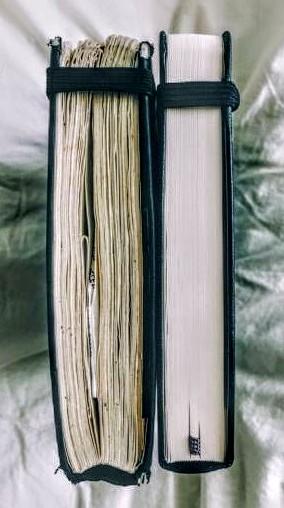

When you see two notebooks, a pristine new one and the scuff edged old one, which are you drawn to? The filled notebook is bursting with life – experiences, deeds and thoughts at a particular time. They may be full of mundanity or of scandal. They may contain secrets or opinions not to be shared but which one feels compelled to set down on paper. Notebooks provide confessional solace – salvation for those of us who cannot find a state of grace in a priest. Conversely, the new notebook, unwritten and virgin, is full of potential. Full of the blank pages of a life yet to be lived, a story yet to be told. Both are magnificent creations, but having set most of my own life down on paper and being a lover of stories, I am drawn to the filled notebook. There is something of the magical about coming across a handwritten diary, bursting at the seams with slips of paper, old tickets and letters. What secrets will it contain? Will it have occult properties and bleed if you thrust a dagger into it? Notebooks are intriguing and weighty with import.

The written life & life yet to be

Compendium of perspective

To reveal secrets, insert basilisk’s tooth

The wonders of memory bound between the covers

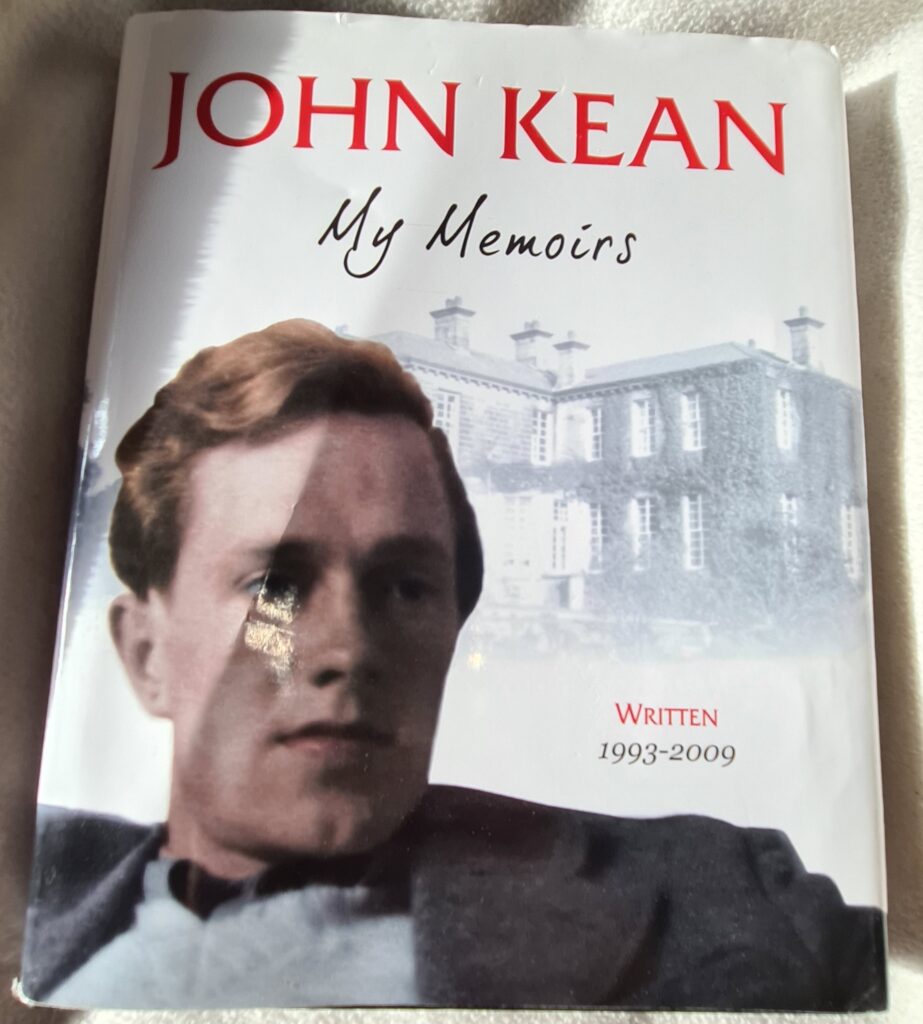

The wife of a very good friend of mine burnt his journals when he died. She didn’t want her children to read certain of his confessions and thoughts about the affair they had with each other when he was still married to someone else. To me, this is sacrilege. But for her, the needs of the living outweighed the confessional of the dead. And, to be honest, he once told me that he wouldn’t mind if his words were interred with him. My father wrote his memoirs and, to his surprise and delight, my sister and one of her children typed them up and turned them into a proper printed book. At his funeral, there was a panicked moment when the family realised that dad had been less than flattering in his memoirs about his ex brother-in-law. The diary was on a table in the centre of the room and retrieved too late. The ex brother-in-law had already got to them – truth will out. Maybe this is why I keep my journals in an old green safe at home. Words can be dangerous in the wrong hands or at the wrong time.

Do loved ones have the right to burn the words we write?

The journals were kept in a safe – to protect the innocent?

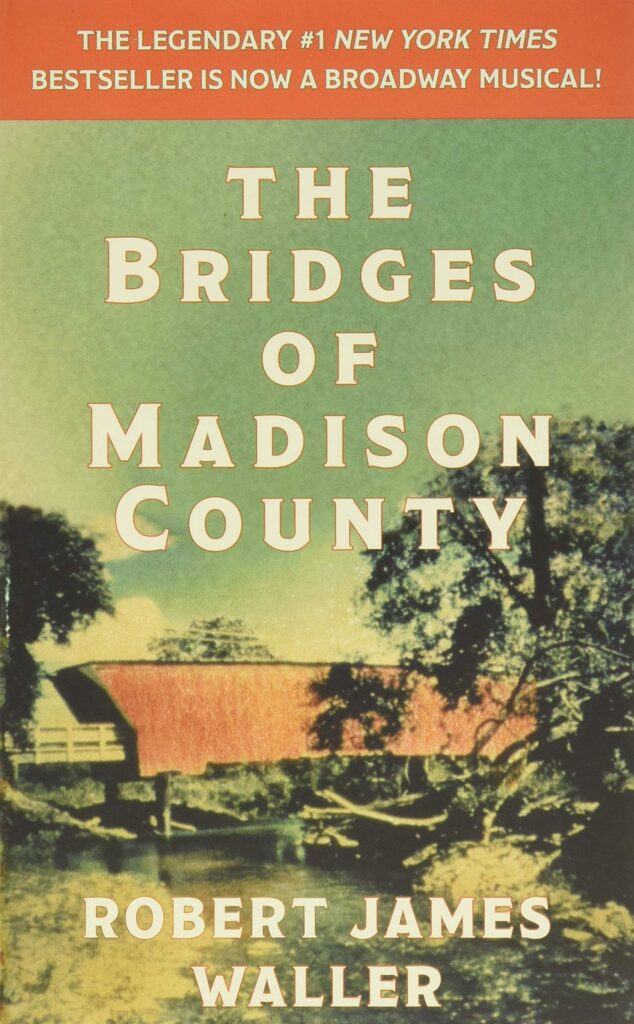

My objection to censorship is the objection of any writer. Spilling our real thoughts and deeds onto the page is revealing as well as a catharsis. Through the written word we often show ourselves to ourself; and we can be known more deeply by our descendants. Of course, we can PR ourselves: leave a tome or two which puts an attractive gloss to a life that we want to present. But journals are often where we go to confide and that confessed reality of ourselves is where the really interesting pieces of our soul and identity live. I kept a journal throughout the terrible years of the disintegration of my first marriage. It is not pretty reading. But its rawness, the immediacy of the reaction to events without filter or reflection or the calming balm of time and resignation, is what makes the journal powerful and informative. When I said that I would leave it for my children to read when I am gone, the eldest one asked “Why would I want to read all that about you and mum? It would be terrible”. I understand that for those immediately affected by events, by a life of huge importance in their sphere, revelation and unvarnished viewpoints and facts about behaviour and attitudes held by a loved one could be supremely shocking. In The Bridges of Maddison County, the son struggles much more than the daughter to understand and forgive their mother’s fling with a stranger who clearly was much more of a true love than her husband, the children’s father. When they discover her diaries in an old shoebox whilst clearing away her things after her death, it is these written words which carry more import, more meaning, more significance than any memento of her life or keepsake. But they also reveal who the person was as a person, not merely in a particular role: father, mother, brother, husband. And this is the interesting bit of discovering someone – their reality and their real voice as an individual on this planet. Their own real life drama.

The backdrop for the drama of a woman as a person not as a mother or wife

Intensity recorded, hidden and revealed

Memoirs – excluding the ‘secret chapter’, which is the really interesting bit

Long hand turned into book form

The written word has the greatest power to reach through time and illuminate. History is sadly filled with partners, parents, siblings, children and well intentioned friends who have torched or torn up screeds of invaluable notes written by the famous and the infamous. What would these words reveal? What insight into the character and events would be given if we could read the first hand accounts? What madness, what betrayal? What love or hate? But the privilege of proximity and relationship seems to endow people with the mantel of Supreme Editor. So loved ones consign to the flames that which they find embarrassing or potentially altering of the dead person’s status. Can this ever be right? Especially if the writer has not expressly wished for their notes to be destroyed. (There is even a case for refusing to destroy testaments when the writer has expressly instructed them to be destroyed after death.)

Clementine Churchill destroyed the infamous portrait of her statesman husband painted by Graham Sutherland. She – and Winston, too – did not like its realism. When he posed for the portrait, Churchill asked Sutherland if he wanted the Bulldog or the Baby: Churchill’s two characteristic poses. Sutherland ignored the propaganda preferences of his subject and painted what he actually saw. He saw an embittered old man, defeated, angry, unleavened by humour and showing signs of the stroke that had been kept a secret from the public. This was not the image Churchill wanted. Famously, the Great Man had said “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it”. Why should we destroy the words of the subject who wishes to confide or bear her soul but accept happily another’s self-glorifying version of events? Because it is uncomfortable for the living? Or uncomfortable for the dead? Every diarist seeks to justify – for every Samuel Pepys there is a Joseph Goebbels. Should we destroy Goebbels’ diaries just because they contain objectionable views?

I revere the written word. Whoever writes it, it is testimony and helps others understand us through time – whether within the family or within the context of world events. Through the written word we accumulate wisdom, insight and experience which is useful. Chronicling the painful course of a separation and divorce or bereavement can be so helpful to others who have to endure the same agonies. To destroy any learning, any source of comfort, does not serve us. It robs us of riches that have been hard won. If my children ever have to deal with heartache, it may be helpful for them to turn to my words and know that another who is close to them understands what they are feeling.

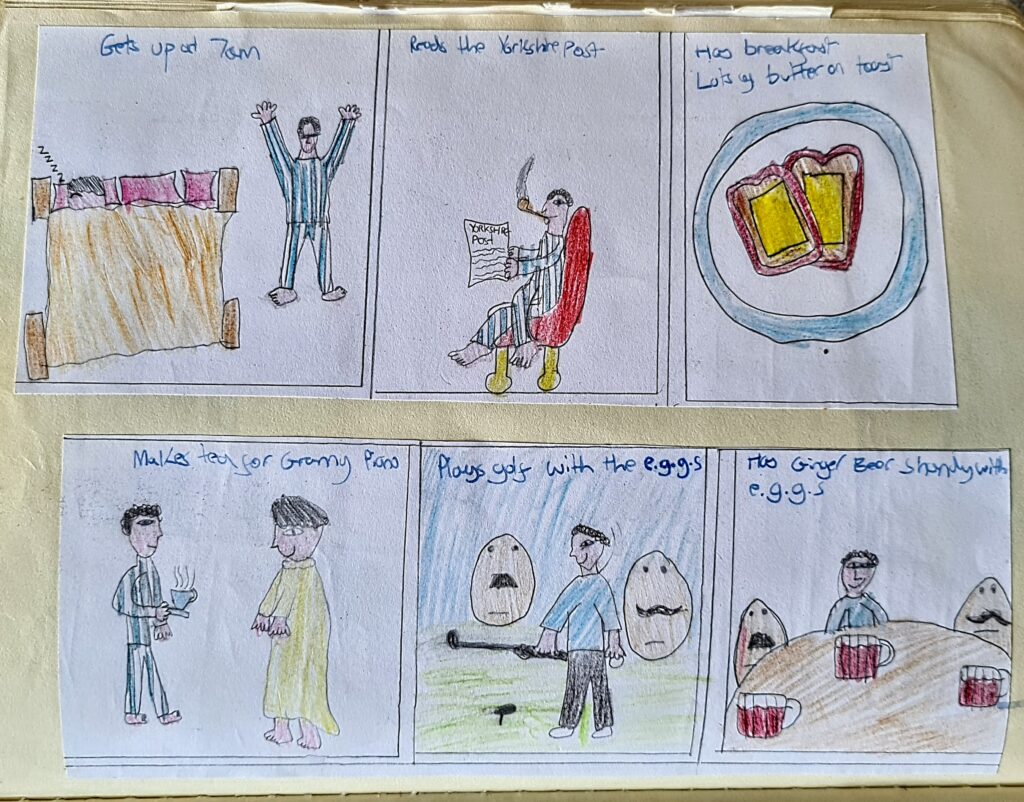

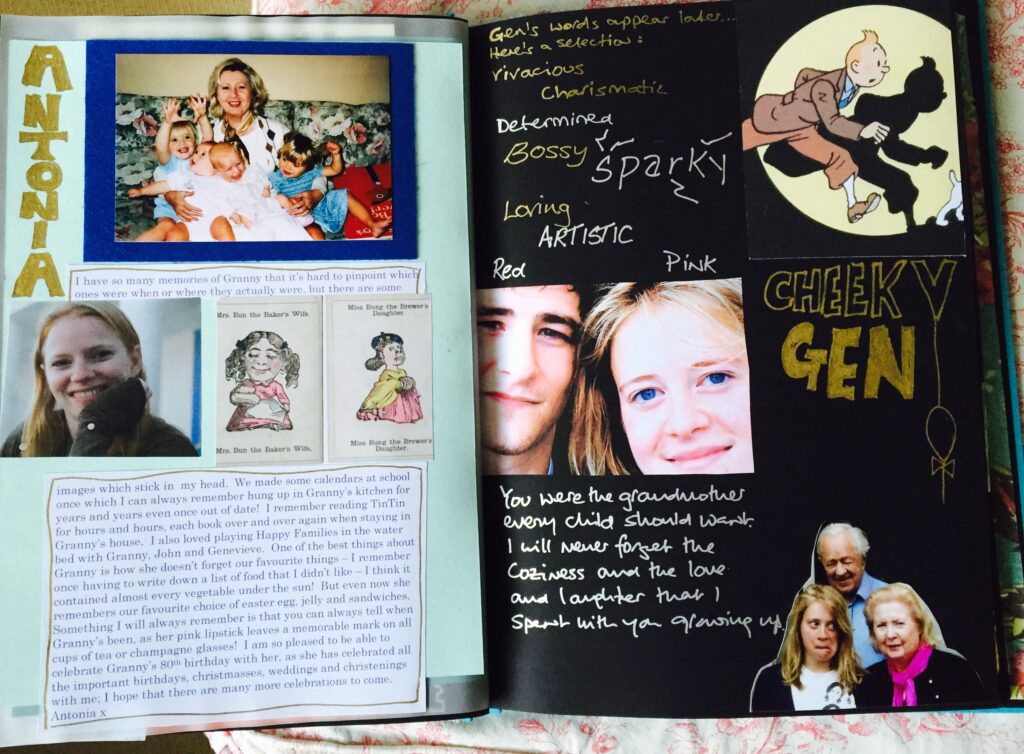

On the flip side, as an author, my favourite present to give someone is what I call a Memory Book. These are hand made, not digital, and there is only ever one of them. They take weeks to make and part of the appeal of them and of making them is the fact that they are unique pieces of art – they are someone’s life rendered in words, pictures, scraps and seen from the point of view of how that individual’s life has enriched those around them. The first one I made was for my father and I still have it. He said in his memoir that “it was the nicest present I ever received”. Over the years, I have made a number of them, the last being for my mother in 2012. People enjoy reading about what other people like about them – perhaps unsurprisingly. Words are wasted on the dead, at the funeral. These books are a way of telling people what you feel about them whilst it is still possible for them to enjoy it.

A grandson’s perception of my father’s life

Two granddaughters’ memories of Sally

Other people’s notebooks are also rich with interest – even those of perfect strangers. Antique book shops occasionally throw up surprises. My old English teacher from prep school wasn’t really a teacher at all. He was an antiquarian book seller and collector of military memorabilia. He combed the bookshops of Edinburgh for valuable ‘finds’ (something valuable that hadn’t been discovered yet and lay inert waiting to be revealed). One day in 2001, he found a find. A series of nine hitherto never seen original drawings by the C18th Romantic visionary poet and artist, William Blake. At auction they fetched £5 million. It is the stuff of legend.

One of the Blake illustrations discovered in 2002

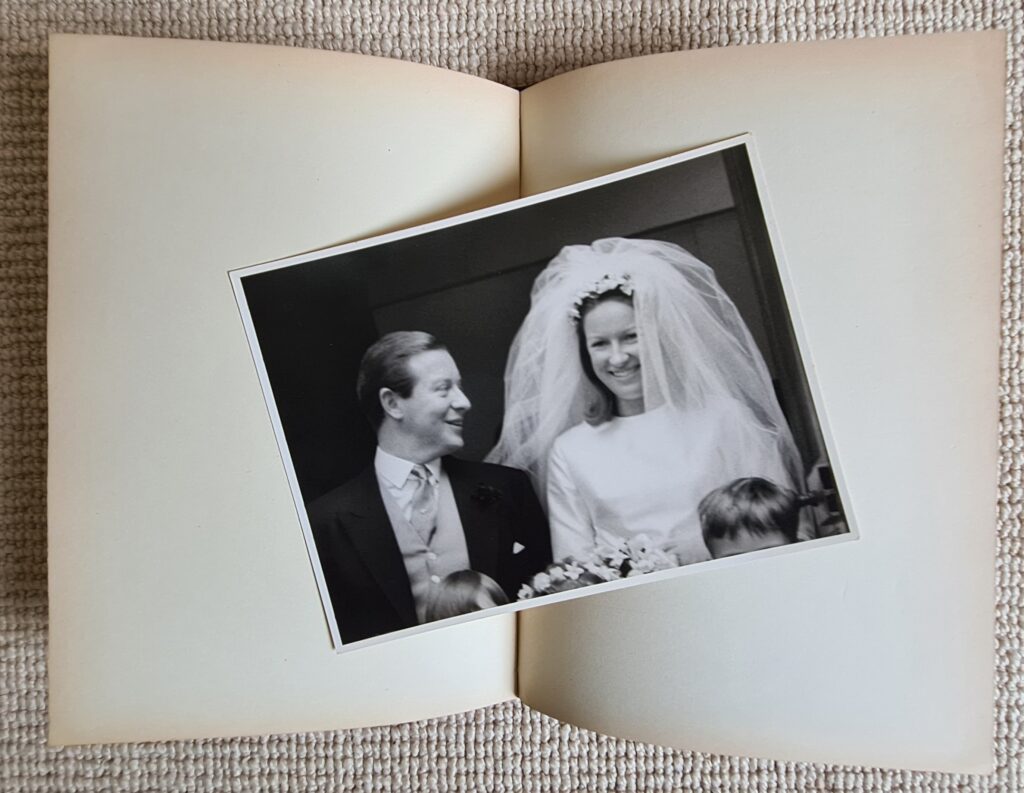

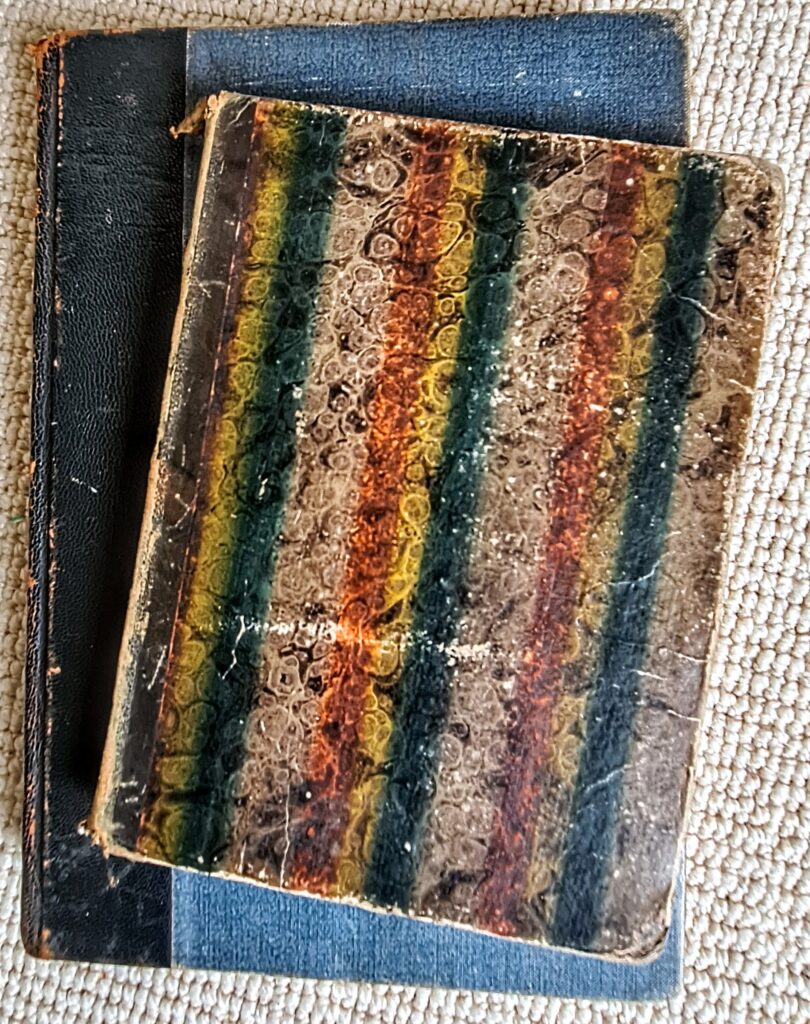

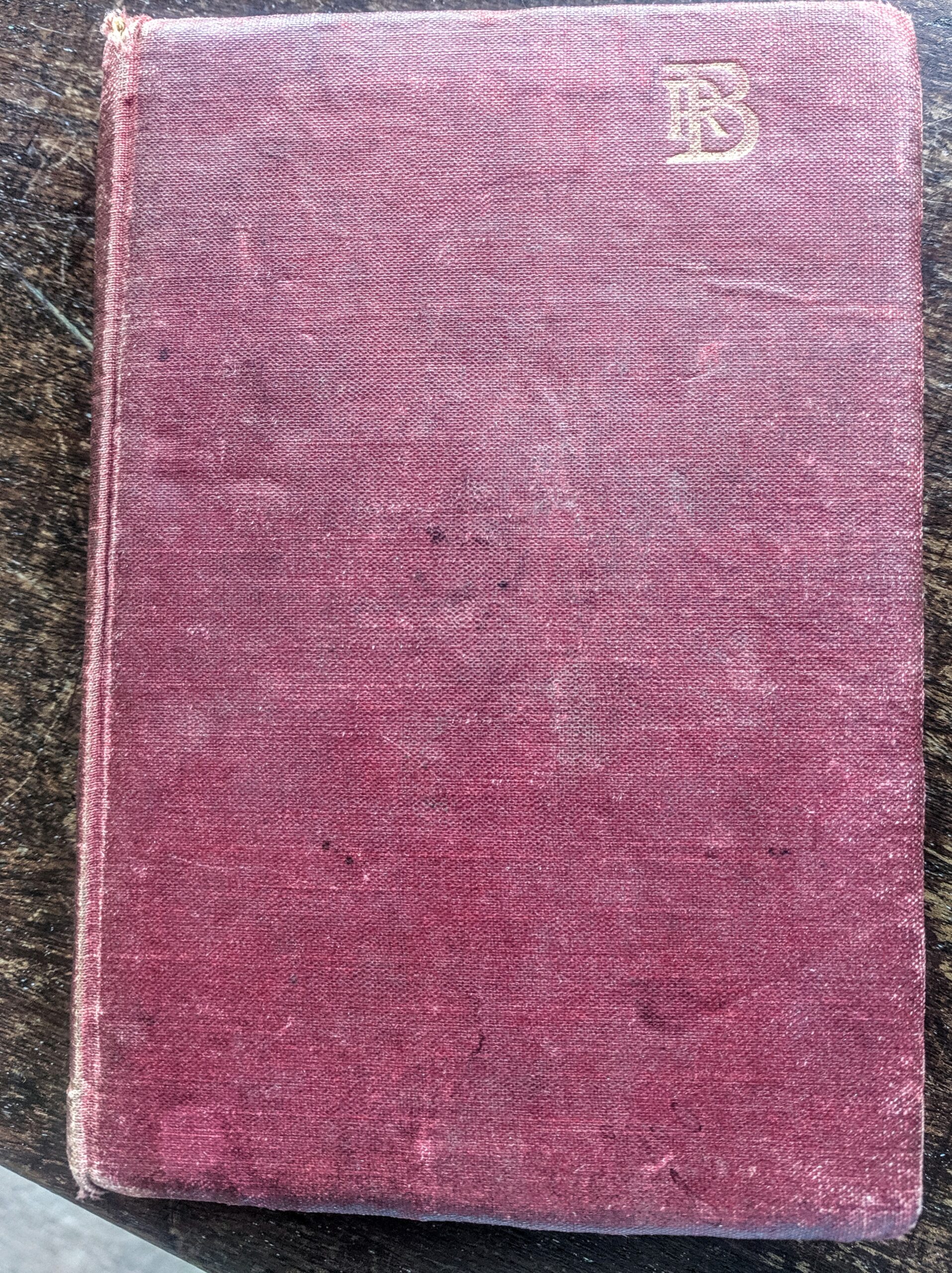

I have never found a set of Blake drawings or Da Vinci cartoons hiding between the pages in any old bookshops, but I have discovered a couple of beautiful journals. Both have drawings and writings and, charmingly, in the bigger and more modern of the two, a single photograph of a wedding couple.

Mystery wedding photo

1796 stage design ideas

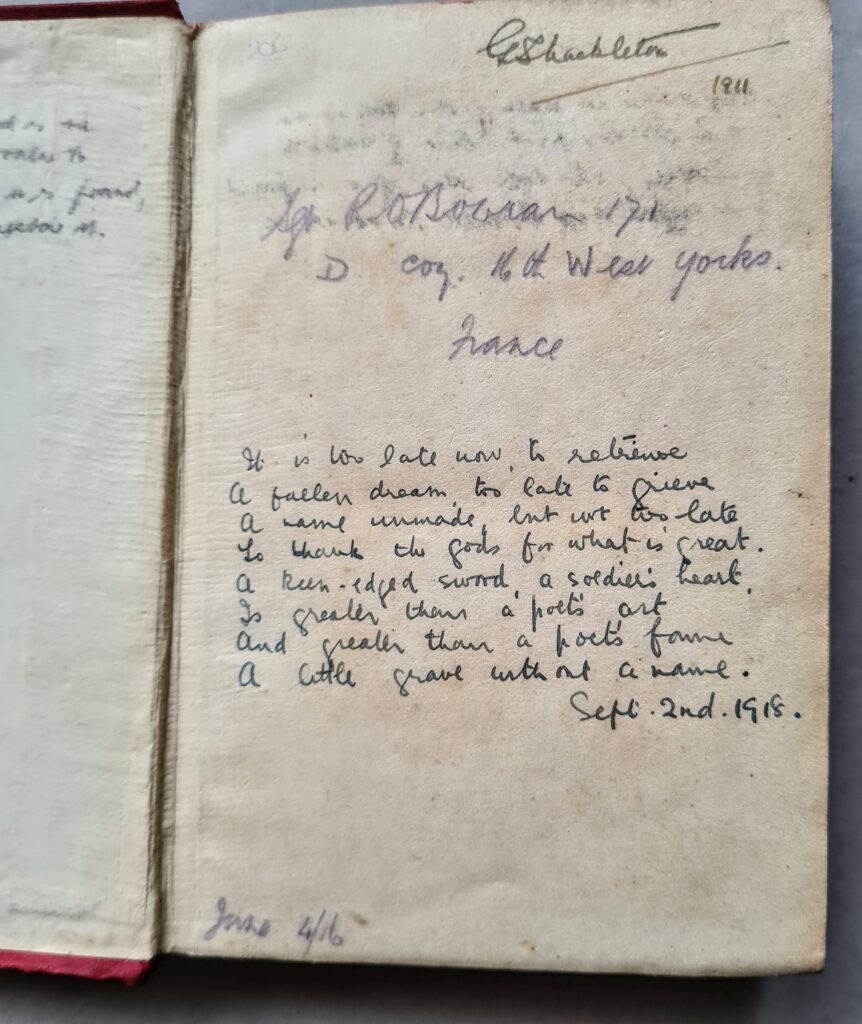

It is from these sorts of discoveries that stories start. And it is from the things that fall from the handwritten pages of such books that tell the true stories of and fantasy worlds within a life. My grandmother had such a secret story which I discovered when clearing out her flat after her death. It is written up in another blog called The Unknown Soldier but in brief, a whole other life spilled out from a little book of Robert Browning poetry: an inscription, a photograph of a husband who lasted only three months before disappearing, missing in action, at Ypres in 1917 and a hand written telegram from the War Office informing my granny of her love’s demise. The book had been returned to her with his belongings when he was killed at Passchendaele only three months after their wedding. He had been given the book to take with him to the Front, for inside it was a message to him from her and, written after his death, a short poem by my grandmother in memoriam. She kept it secret until her own death. These are the tragedies of life. What my grandmother experienced was experienced by millions of others. But her story was unique and all the more poignant for its singularity. The statistics of World War I are horrific; one woman’s story brings the statistics to life.

Notebooks found at my grandmother’s – 1796 and 1950

Robert Browning’s poetry – leant for comfort at the Ypres Front 1917

My grandmother’s In Memoriam poem

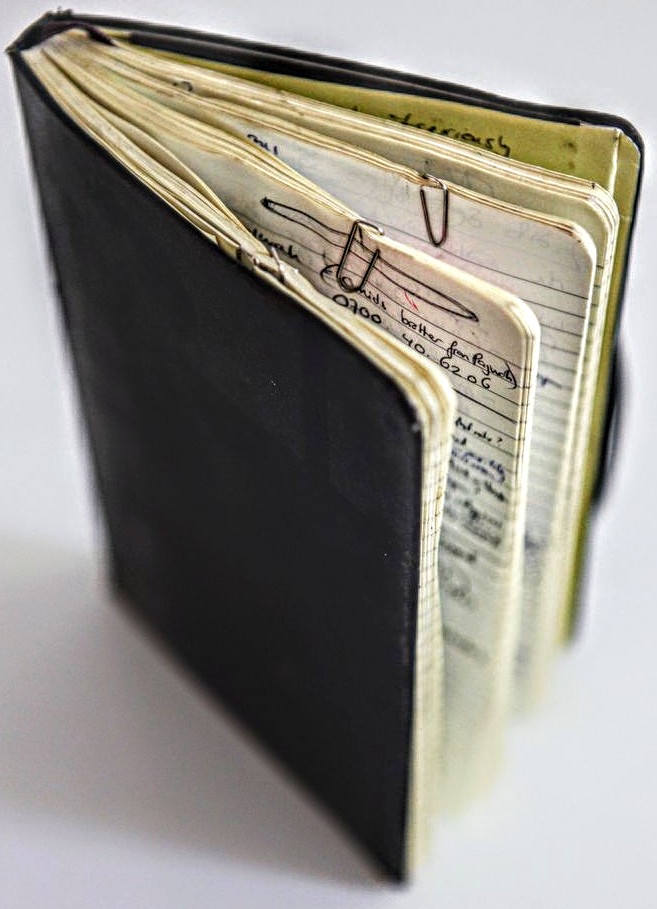

What is written in notebooks, handwritten at the front of printed books and in the margins of books is the real history of an individual’s life. Even the mundane notebooks from business meetings and conversations can act as triggers to memory. They can reveal a nuance in a conversation. Or help you piece together what you or the author were thinking – doodles in the margin often tell us lots about the level of interest in the meeting or the pre-occupations of that particular moment. I keep all my work journals – some thirty or so Moleskine’s from the last two decades. Leafing through them occasionally can be therapeutic. It can also help me to recall esoteric phrases or facts which can come in useful or provide an excuse to reconnect with someone. There is a huge power in writing things down.

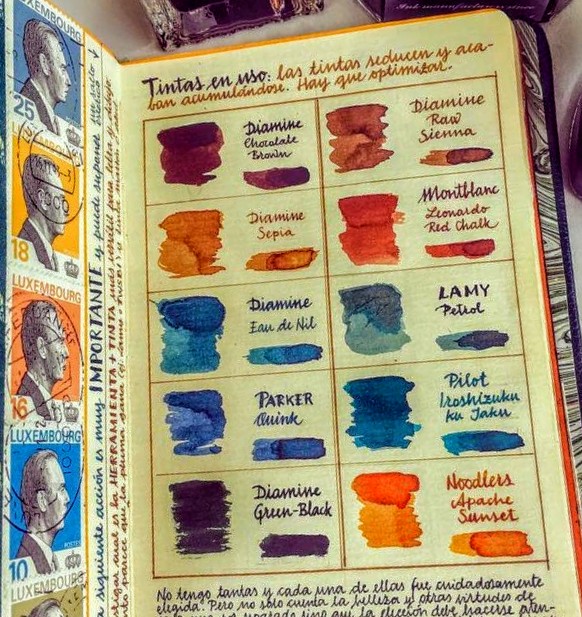

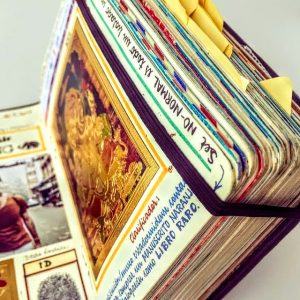

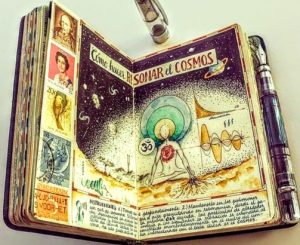

There is a Spanish artist, José Naranja, who has made his medium the notebook. There are some examples below. The notebooks are made up of collages, sketches, illustrations and calligraphy inspired by his travels. Most of us aren’t up to this level of beauty, but they show how extraordinarily individual a notebook can be – in both content and appearance. As with life, it is what you do with it that makes it colourful and beautiful or dull and lifeless.

José Naranja’s palette

Notebooks as works of art

Absorbing fusion of illustration & writing

Pouring hours, days, weeks into the creation of notebooks has kept me nicely occupied for decades. By now, I have a catalogue of work and a trove of volumes to enjoy and, one day, for my children to look back on their lives as reflected in my eyes. And for them to understand me as a man, not only their dad. To create such a catalogue, the main resource you need is time – I get up very early to steal time from the day for this passion. My inspiration is my imagination, those I love and the experiences and beliefs I want to record. The rest is just enjoyment.

Caran d’Ache

Sharps

Blue pencil for editing

Lettera 22

Stack of notebooks

Mont Blancs

Inspiration