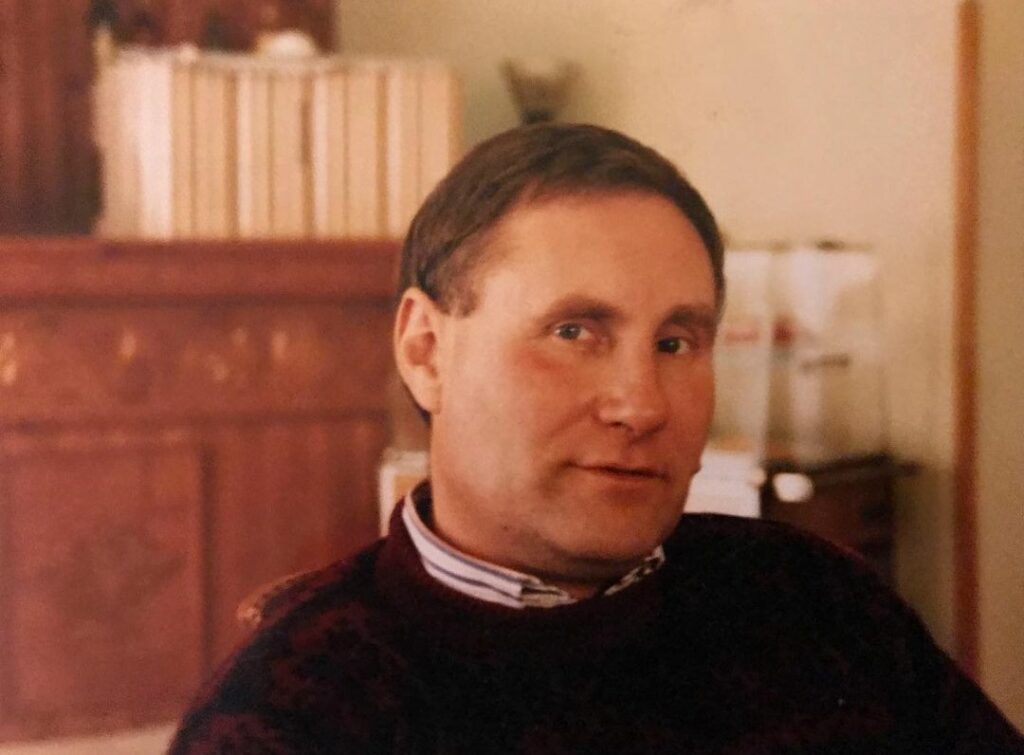

I recognised Jeffery the moment he walked through the door, even though I hadn’t seen him for forty-four years. He was wearing an off-white cotton twill jacket and slightly lighter trousers, all set off with a colourful stripy tie – “fake regimental”, he laughed. The look was colonial gent, fitting for a man who visits India several times a year to seek out Raj memorabilia. He was every inch the man I remembered. He hadn’t even aged much. The face was familiar, in spite of the years in between, and the eyes still flashed with that mischievous defiance I remember so vividly. Jeffery was always imperial without being imperious. I called to him and he spotted me. We shook hands. All the years disappeared and off we went, like old friends.

A few weeks earlier I had managed to track him down on Instagram – the only social medium I do not use, ironically – after years of sporadic attempts to find my first and favourite English and History teacher from 1976-77. The only record of him was a newspaper story from 2002. Jeffery had discovered nine original drawings by William Blake in a bookstore in Edinburgh and sold them at Sotheby’s for a handsome profit. After that, the trail went cold. But my perseverance was rewarded. I wrote to him at the email address mentioned on his Instagram account and hoped he might vaguely remember me and reply.

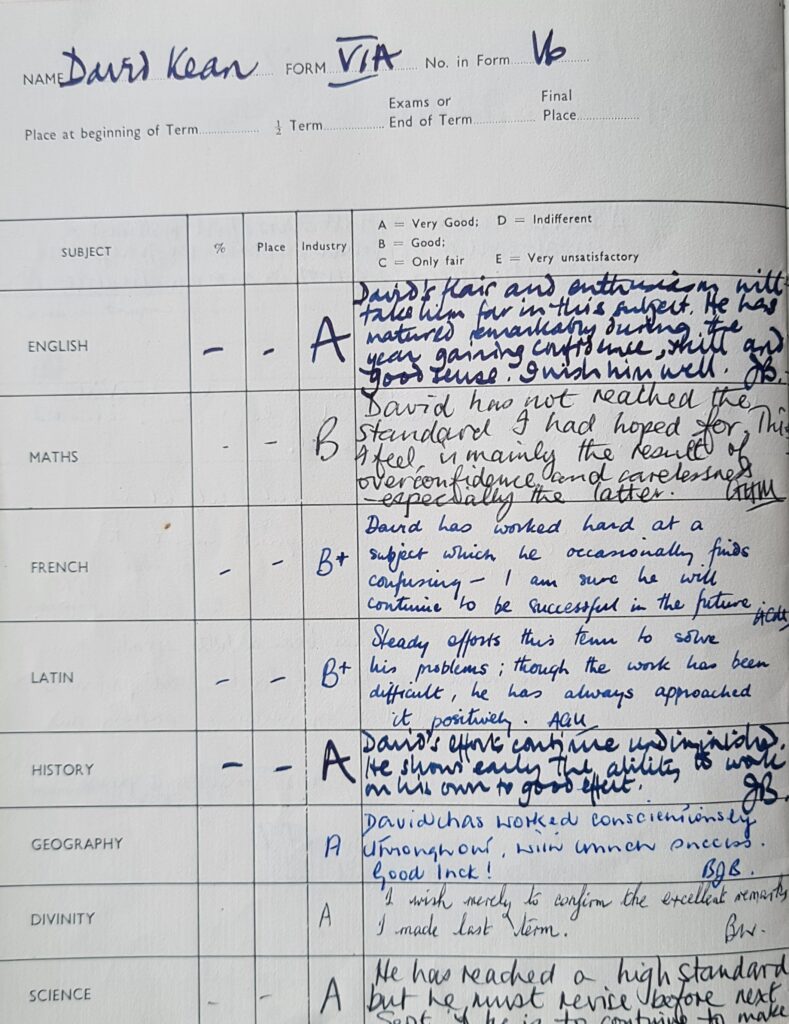

Jeffery was easily my favourite teacher. He only taught sixth formers and he had a reputation for being acerbic. He brandished an outsized black Mont Blanc Meisterstuck, from which flowed scrolls of very dark blue ink in a glamorous, spiky script. I bought one years later, when I could afford to, and it is still my most prized pen – a symbol of the craft of wordsmithing. The one Jeffery used set him apart from the other teachers: it was, like its owner, conspicuous – the very opposite of anonymity. A pen and a man of note.

Jeffery could exude menace which rose to volcanic fury if provoked – I remember a short fuse – and he didn’t suffer fools. But he was also quick witted and affable and if you got on his sunnier side, you would bask in the brightness.

He seemed to like me and as a consequence, I wanted to do well in the two subjects he taught. Or I seemed to do well in the two subjects he taught and he liked me as a consequence. One or the other. Or both. And if Jeffery liked you, if you were one of the coterie of students that he favoured, you were invited to a summer party at his home in Headingley, up near Leeds University, to play croquet. His house was full of antiques and militaria – like an Aladdin’s cave of curiosities.

Under Jeffery’s tutelage, my written English blossomed and it was his encouragement which propelled my desire to write. When I moved to St. Peter’s in York, I was able to impress my next English teacher – another great nurturer of my writing ability – David Hughes, by using the word “anachronism” correctly in my first essay at the new school. My essay was read aloud by David Hughes to his A level students as an example of good writing, which really got my confidence up. That was Jeffery’s doing.

But it is history which really binds us. With Jeffery, it came alive. He gave me a lifelong passion for the subject – helped along by the fact that he had turned a hobby into a livelihood, both academically and in commerce. We both seem to enjoy a uniform and the parphenalia of Empire. We are both fond of spectacle. And of the many fascinating personalities peopling the centuries. His instagram feed is a moving tapestry of the esoteric and the eccentic, the beautiful and the curious artefacts of times past. This enthusiasm infected me and makes me an avid archivist of our family’s history and hoarder of the accoutrements of my grand forebears. Watches, cigarette cases, snuff boxes, photographs, cap badges, regimental buttons. And small mementos of my numerous excursions to historical places – the trip around the Pelopennese with my eldest son, Sam, to Pompei, to Rome, the temples of Sicily, the pyramids, Istanbul, Jerusalem and sailing around Odysseus’s home – the island of Ithaca. And further afield to Japanese occupied Singapore, the temples of Cambodia, Goa and various Royal Naval dockyards in Antigua, Malta and Gibraltar.

We met for lunch at the Berners Tavern in Fitzrovia. Talking to Jeffery was incredibly easy. I am sure he travelled from his home in Cheltenham with slight trepidation. It’s a long way to travel to London to run the risk that I was a pedantic, balding accountant with a morbid fascination for my own ailments, a tight fist and halitosis. Luckily I’m not any of those things and the years between us disappeared with the first sip of gin and tonic. As he spoke, I realised how similar we were. He is as bored by detail as I am; we both like to tell a story; he is as judgemental of others; there were similar reference points, a similar world view, identical turns of phrase and mirrored mannerisms. There was the mutual love of history, of course, for living life fully and a predilection for the unconventional – whilst simultaneously admiring tradition. There was our effrontery at being told what to do and the assumption that the way we saw the world was self-evidently, clearly correct. And there was our respective failure to receive a Queen’s Commission as an army officer. His on the rather cruel medical grounds of having admitted to an insane uncle, mine, less gloriously, to my having discharged a round of ammunition into the Regimental Sergeant Major’s foot on my three day trial with the British Army On the Rhine. Luckily the round was not live.

“He’s just like me”, I thought.

And then it hit me. Jeffery wasn’t like me: I was like him.

I suppose there’s no wonder in it. What impressionable 12 year old boy wouldn’t be struck by a larger-than-life, Rolls Royce driving, militaria collecting, well spoken, flamboyant one off like Jeffery as their teacher? He was hardly anodyne or forgettable, like all the others. Jeffery was somehow different. Better. A cut above. Way above. He was loud, supremely self-confident. He was forceful. And he had interests outside school and teaching. It always felt that he was teaching to fund adventures in more interesting endeavours, such as hunting for exotic antiques and archaeological rarities. Like a sort of British Empire Indiana Jones. He was an excellent teacher, got us to parse sentences (I remember him shouting at another boy because he didn’t know what part of speech ‘was’ was) and directed us in productions of plays. It felt that he just wasn’t like any of the other teachers – more Robin Williams in Dead Poets Society, but in a pith helmet. Jeffery had style.

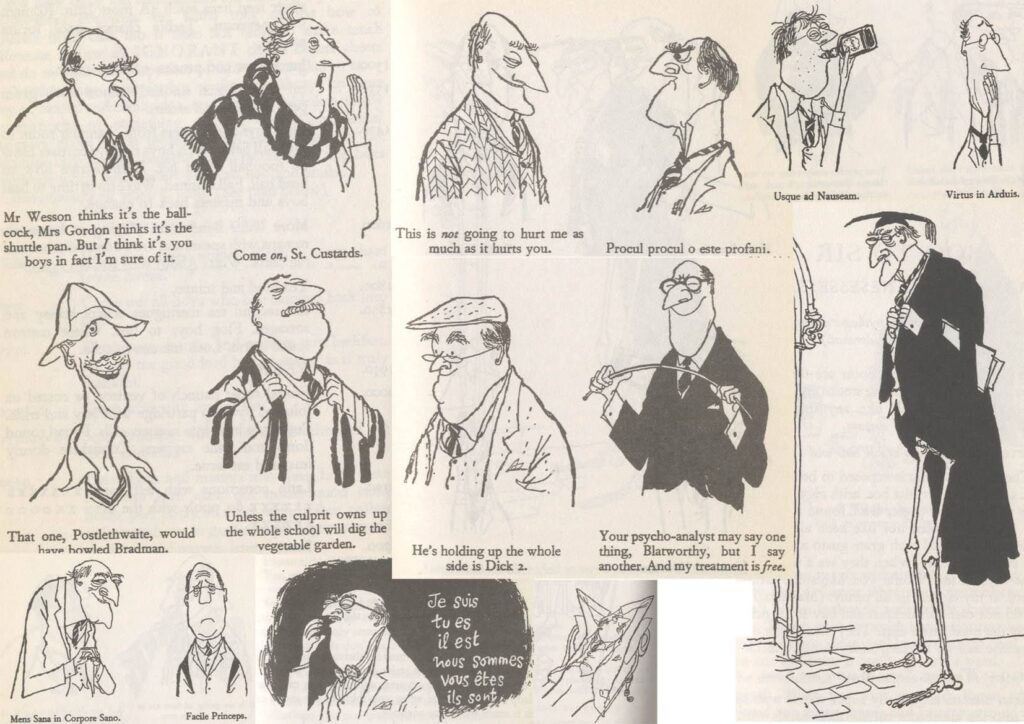

Over our lunch, we discussed the oddments that were the other staff members of the prep school we had both attended. Obviously, he had a rounder perspective than I did as the other teachers were his peers. But we both agreed they were an extraordinary collection. The only one who seemed vaguely normal to Jeffery was Mr. Hopkins, who he went into business with and who collected toy soldiers. All the others were like characters who had escaped the staffroom from the Molesworth books by Geoffrey Willans and Ronald Searle.

Moorlands School was presided over by a monocle wearing Captain Mainwaring-like headmaster, Gordon Ramshaw. Mathematics was taught by Mr. Lapish, my housemaster, who looked like Captain Haddock from the Tintin books, wore sandals over socks and was a vegetarian, which was suspect in our eyes. He also refused to buy a television, which made us all feel sorry for his children. “Odd”, observed my lunch companion. Mr. Dent, the irascible art teacher, who always seemed to me to be incredibly angry that he had ended up teaching art rather than making it. Mrs. Jennings, mathematics, who wore a military style brown leather jacket complete with a Sam Brown – a woman in comfortable shoes, perhaps (as Alan Bennett would say)? Mr. Burroughs, who wore heavy woollen three piece suits complete with fob watch chain, come winter or summer, and whose hair was plastered to his head with some sort of grease. An Edwardian exterior with Plantagenet ethics. His great boast was that “not even the Queen of England could make me teach you”, made to any eight year old boy he felt had failed his stringent behavioural standards in the classroom. Ben Walby, who lied about his age in order to get a job (too old), and whose bumbly, affable exterior hid a fierce temper and, judging from the end of term reports he wrote about me, a sadistic streak. Mr. Pryce, who used to smoke his pipe in class and hid it in his jacket pocket if the Headmaster popped in. (Jeffery recalled that a boy once ran into the staffroom and said that “Mr. Pryce is on fire” – the pipe, resentful of being hidden from sight in the recesses of its owner’s pocket, had set fire to his jacket.) One member of staff had a missing leg. Two had pince-nez (you don’t get many of them to the pound nowadays – nor then, come to think of it). But worst of all, to my snobbish sensibilities, one who used to umpire cricket matches wearing a tartan Tam O’Shanter. A sartorial lapse of taste which used to prompt raised eyebrows from the Panama Hat Brigade at our boarding school hosts – very infra dig. Mr. McTaggart. NOCD.

Jeffery did have class and he drove to school in a classic 1930s Rolls Royce shooting break, replete with a wooden strutted back section. It looked as though the aristocrat of English motoring had taken sexual advantage of a Morris 1000 maid from below stairs and created bastard offspring. But it was a very fitting carriage for a man who said he was more ‘cavalier than roundhead’. As we talked, I recognised more and more of where many of my own opinions about the world had been shaped. Jeffery told me about his life, his birth – during an air raid on Poole harbour – and his exotic back story. We share a scandalous story about our origins. We covered the four decades between our last meeting in languid anecdote. Jeffery is not a lists or bullet points type. Stories, bon mots, asides and funny observations were woven into the fabric of our conversation. Characters appeared, left and returned. Over the course of two and a half hours that went in a flash, we barely scratched the surface. My, it was fun.

An old flame of Jeffery’s had told him about the restaurant where we were meeting. She was a restauranteur and they had run a pub in Rye for eight years. “None of the paintings are real”, she had told him. And it’s true. It was such a brilliant comment, like Alan Clarke’s put down of Michael Heseltine, that he had “bought all his own furniture”. The Berners Tavern is a grand old room, huge high ceilings and all on a big scale. Hundreds of pictures in extravagant gold frames adorn the walls from floor to ceiling. The frames look like they cost more than the pictures. (I learnt the following day at another lunch that they do.) Jeffery said that he could have provided them with originals and they’d have better quality and have got better prices – a very Jeffery observation: a put down and profitable remedy in one sentence. I just know that would be true. Next time we’ll go to Rules in Covent Garden, where the paintings are originals.

The food came and went. The service was a tad overly solicitous but fine and there was a funny disparity in the relative size of our portions: Jeffery received his gargantuan starter – a salad as large as Waitrose’s entire produce section – as I was handed what looked like an infant’s scoop of ice cream and an alfalfa sprig adrift on a sea of white porcelain. It was actually duck terrine and delicious, but he had Cavalier helpings and I, Roundhead. Fitting given that I am a Republican and he a Royalist. (Jeffery generously offered to tell the authorities to cut me down from the scaffold should my traitorous beliefs catch up with me.) We parted having enjoyed our time tremendously and four decades will not go by before our next meeting. There is too much fun to be had. And too much personal history to be both relived and made.