A snowstorm rages outside my apartment in the Alpine ski resort of Meribel. I am on the phone to my brother. I am only half listening because it is change-over day – Sunday – in resort and I am about to go off on my evening rounds to welcome the new guests we have just settled into their chalets.

‘You must come up and stay with us when you get better…’, says my brother.

He carries on talking about his invitation for me to stay a few nights in the bosom of family when a little question mark enters my head. Did I just hear that? Did he really just say ‘when you get better’? And another question. ‘What does he mean by that? I’m not ill, am I?’

‘Sorry. What did you say?’ I ask.

‘I said, you must come up and stay with us.’

‘No, I heard that. I mean the bit about ‘when you get better’. What do you mean?’

My brother um’d and ah’d a bit. He knew he’d given himself away.

‘Well, you know. I mean when you come home, when all this, well, whatever it is you think you’re doing in the mountains is…over. When you’re…I didn’t mean better, I meant when you come back.’

But the cat was out of the bag. In a lapse of concentration, he had committed the cardinal and very un-British sin of saying what he thought. And he clearly thought I had lost it, gone Absent With Out Leave, round the bend, loopy. He thought I had had some sort of mental breakdown. He thought that I was ill in the head.

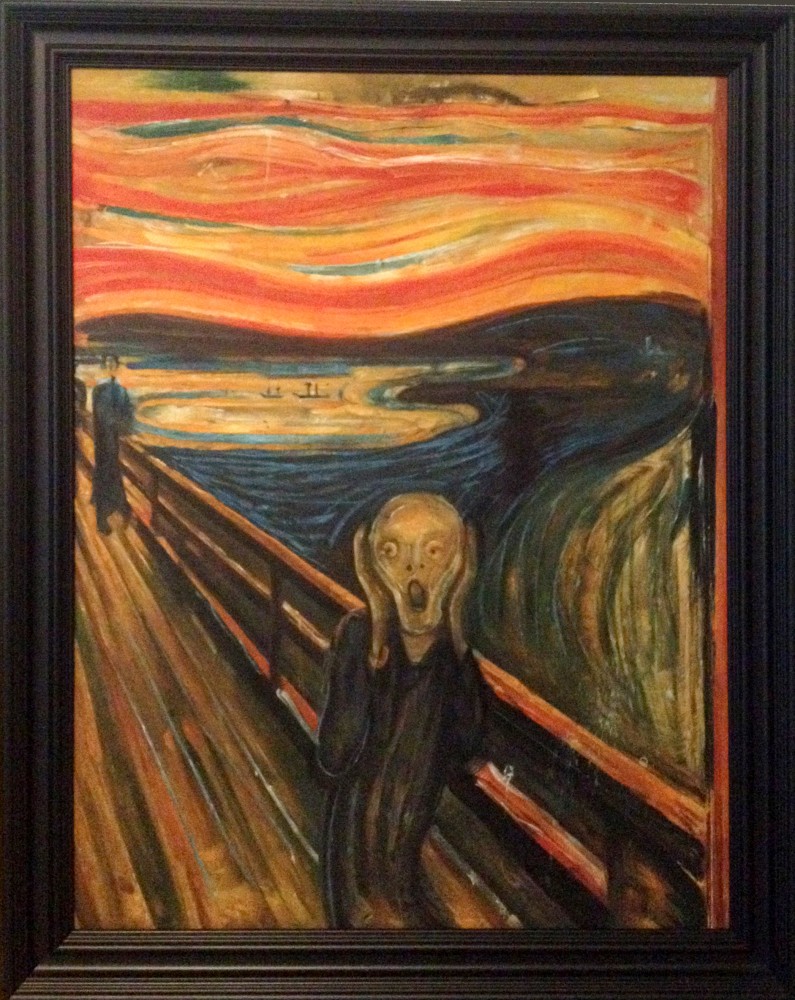

All my relatives and friends thought that this sabbatical, this break from normal life to do a season in the Alps aged fifty, was a sign of mental illness. I was having that dreaded thing that all normal people live in fear of having: a full blown midlife crisis. When people talk about other people having a midlife crisis, although they say it sotto voce, there are klaxons and red flashing lights going off all around them. It is always articulated as a quiet scream. A midlife crisis is, for most people, something to be ashamed about. Like alcoholism or drug addiction.

My brother thought I was ill – hence the need for me to get better. The problem was, I felt saner and more mentally stable than I had ever felt before.

Midlife crisis has a very bad reputation. Whether you are male or female. My perspective is male, so it’s that experience I can write about with some authority. I have met women whose husbands have gone through a midlife crisis and raise their eyebrows to the clouds just at the mention of the thing. Watching your husband – or (as is usually the case) soon to be ex-husband – have one doesn’t seem to be much fun.

When you have one, people humour you. But you know that they’re thinking ‘poor sod’ as they smile with faux sympathy at your new theories on the meaning of life, look askance as you swap your jumbo chords and Timberlands for Thai fisherman’s trousers and festival wristbands and grimace when you confide your discovery of tantric sex.

They needn’t. A MLC is a wonderful thing and to be highly recommended. It can be very painful and hard work at times, but is ultimately rewarding. A bit like a Turkish bath but for the soul, and without the positive PR.

If you’re having a midlife crisis – and we’ll talk about the telltale signs in a minute – don’t look for understanding from your normal crowd. It will not be forthcoming. They are desperate not to catch a dose of MLC from you. Wives will want to keep you away from their husbands in case you infect them. Men will cock their heads in faux sympathy and pretend to give your self-evidently insane ramblings (to them) a fair hearing. But inside, they are shaking their head with sorrow.

What you need to tell yourself is, they are not ready yet. They have not reached the same place on the journey of life that you have. But they do not know this. They just think you have lost your grip on reality and become emotional – two things most middle aged men are terrified of. But really, what has happened is that you have lost grip on their reality. And opened up your heart to self scrutiny.

What is a midlife crisis?

There is lots of guff written about midlife crisis. It’s mainly dry, academic, dull cerebral stuff that misses the point. The point is the heart, not the head. A midlife crisis is an emotional reaction to the realisation that life is half over. It can be triggered by an existential realisation that you are mortal or by a setback in life. The death of a parent, loss of livelihood, the breakdown of a relationship, the death of a loved friend, children growing up and away from home. Or any combination of these overwhelming forces that compel you to reappraise your status in the world and confront the reality of where your life is at in these changed circumstances.

Who knows where this reappraisal will end up? In my case, it resulted in the realisation that the first half of my life, I hadn’t been living my own life, but someone else’s. My father’s idea of a man’s life, in fact.

I had been a good boy, or, in transactional analysis terms, I had been an ‘adaptive child’. I had done as I was told. I had done what was expected of me. I had aimed to please others rather than think for myself. That increasingly loud sense that there must be something else, that there must be more to life than this, was my ‘free child’ wanting to play and to create, to be heard and acknowledged. The part of me that was the real me. The me that wanted to do its own thing, to have adventure, to stick two fingers up at convention. That part of me that, when my dad asked me what I wanted to be after I left university, answered: ‘Indiana Jones’. (This elicited the response “don’d be so fucking stupid” when the more helpful reply might have been “tell me what you mean by that”.) To see what lay beyond and to the side of the path that had always been laid down in front of me and which I had blindly stumbled along without ever straying. At 21, fresh out of college, I missed that opportunity. At 49, long overdue, I seized it.

Spotting the symptoms

There is a funny side to midlife crisis. Those two great BBC classics from the 1970s The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin and The Good Life are testament to the comedic potential of midlife man’s search for something more – when the country started to talk about things like mid-life crisis. The crisee may appear to have lost his grip on reality to others, but to himself, he appears to be seeing things as they really are for the first time. And he cannot understand how he could have been so deluded for so long. Or why more people cannot see through the charade of the hamster wheel life of chasing achievement in career and society. In this sense, he becomes both a Shakespearean Fool (pointing out the absurdities) and Lear-like (full of self-regard). A fall is inevitable. Like all great comedy, there is a great pathos alongside the humour.

Such programmes are necessary. Too much of the literature that’s out there on the subject follows the dull theme of survival. How to survive your midlife crisis. How to survive your husband’s midlife crisis. A midlife crisis is so much more than something to be merely ‘survived’. What’s wrong with:

- Existential disillusionment with the banality of everyday life (it shows you’re thinking and sane)

- Feeling that everything you have achieved has been a waste of time (“remember thou art mortal”, as slaves would whisper into the ears of Roman conquering generals as the made their triumphal progress through the adoring crowd)

- Affair with a much younger person (rediscover sex)

- Loss of weight and shaping up for the first time in decades (your doctor will be pleased)

- Newly acquired interest in clubbing, new forms of music and festivals (shake up your tastes, which probably atrophied at the age of 31)

- Wearing new clothes and different styles (didn’t do David Bowie any harm. Why dress like you were dressed by your mum all your life?)

- Buying a sports car or a BMW motorbike (why wait until you’re a retired octogenarian to enjoy the thrill?)

- Experimenting with drugs (it can change your perspective and make things more lucid)

- Interest in esoteric writers such as Paolo Coelho and Oriah Mountain Dreamer and YouTube videos of Buddhist monks lecturing on ‘letting go’ (interesting alternatives to The Financial Times or the News at Ten)

- Travelling off to find (re-create) yourself (now we’re talking – proper adventure of the interior and exterior landscape)

A midlife crisis is a chance to challenge what has been taken as given or merely assumed. It is a break down not a breakdown: a break down or a dis-assembly of all the pieces that make up your life. You are just at a place and time when some of the big pieces of your life are no longer usable in their current form. Your values, for example. Like many white, well educated men, I inherited pretty much all of my values from my parents, from school, university, my peers and my job and colleagues. I moved in very restricted circles and never really experienced the wider world. Four weeks a year on vacation seeing the world from the pool terrace of a five star luxury hotel and occasionally venturing out of the compound to wander the streets for an afternoon and to see what the locals are like does not constitute meaningful interaction with the great big world out there.

As I said, I had been a ‘good boy’ and done precisely what was expected of me:

- gone to university

- got a career

- got married

- got a mortgage

- had children

- sent my children to private school (so they could go to university and, well, see list above)

- ‘done well’ at work

- enjoyed holidays skiing in the winter and villas by the beach in the summer

- got nice cars and houses and lots of stuff

- moved in circles of people ‘just like us’

- got a pension which was invested in oil, tobacco, armaments companies and various other nice industries that offered a good return on investment

- worked for merchant bankers, booze companies, cigarette manufacturers, car companies, disposable fashion brands, gambling gimmicks, double glazing outfits, fizzy drink makers and a host of other businesses which didn’t add much to the sum of human kindness

I did it all. By the book. The Sloane Ranger Handbook. Unthinking, unchallenging, by rote. As a girlfriend at the time put it so unkindly: I lived my life as if it was a painting by numbers kit.

But something was wrong. I remember one Sunday in the early 2000s when I lived in London just bursting into tears. ‘I am not happy’ I complained to my then wife. Like Tom Goode, the disenchanted middle aged executive in the 1970s BBC sitcom The Good Life who chucked in his job as a middle ranking illustrator at a cereal company to start a new life growing his own produce in Surbiton, I knew there was something missing – ingredient x. I just didn’t know what x was.

A few years later, in our own version of The Good Life, we moved to live in Cornwall and I gave up my job in the corporate world. But instead of being the answer, Cornwall just asked harder and harder questions.

They say that everyone who goes to live in Cornwall is either divorced or ends up getting divorced. It is a place that finds you out. They also say that Cornwall, shaped like the end of the toe in the Santa’s stocking that is Great Britain, is where all the nuts end up. Whether Cornwall caused my midlife crisis or hastened it or was just the right place to be when it happened I cannot say for sure. But it exposed the cracks which life in London had hidden from view. Very quickly.

Cornwall was characterised by having to confront a lot of hurdles: divorce, a series of doomed love affairs, a number of ethical confrontations at work, financial crisis and a lot of soul searching. But I don’t regret a single one of the hurdles I had to overcome. The decade between 2005 and 2015 was like a very personal, very elongated corona virus for me: it forced me to shake all the pieces, work out what was important to me and what wasn’t, jettison the stuff I didn’t want or need any longer and make a new life according to the new picture I wanted to create.

Stop being so scared: why everyone should have a midlife crisis

You know the funny thing? That more people don’t have a midlife crisis. Why? Because a midlife crisis is a wonderful, miraculous, necessary and wholly enriching thing. I am so, so glad I had mine. It is both a destructive and a creative process. People are terrified of destruction and yet it is the defining force at work in the Universe – life always ends. But in ending, it creates new possibilities. People are terrified of change and of suffering, and yet change is an unavoidable fact and all life, according to Buddha, is suffering. We hear these truths all the time and we pay lip service to them, but when we are actually given the opportunity to experience them all, we run for the hills. Or rather, we don’t run for the hills – it was me that did that when I went off to work in the Alps. Instead, we hunker down in our little world, circle the wagons, try to keep a lid on our feelings and maintain everything exactly as it always has been. Pretend it’s all fine. We wait for it to pass. Why? Because we are terrified. Terrified that our little house of cards will tumble down. So what if it does?

This is dealing with reality. Dealing with reality is not to ignore your own truth. To suppress it or deny it. If you do, it will find you sooner or later. More importantly, you cannot shelter your loved ones from what you are going through. Yes, they may find it difficult. Yes, there may be consequences for them and for your relationship. But part of life is seeing people for who they really are, not just seeing them as some supposedly perfect ideal. People, real people – real parents, lovers, colleagues, friends – are imperfect flesh and blood. Vulnerable. Allowing others, even your own children, to experience that vulnerability, is to show them you too are human and fallible. It is honest when most parents want to create a facade of invulnerability, which just infantilises their offspring in a perpetual state of childishness.

The benefits

I emerged from my mid-life crisis a better, less angry person. Free from an inherited set of suppositions about the world, about life, about work and career, about relationships and about values I imbibed from my parents and my upbringing. My mid-life crisis broke me and also set me free. All the most important relationships I have in life ultimately benefited. I am a better father, I hope, and a better husband (second time around). Those relationships that had served their time, ended or ended in one form and reformed in a more suitable form – from first marriage to friendship, for instance.

The baggage my midlife crisis helped me drop was a blessing. I just couldn’t carry it anymore.

There was a homeless person I remember who used to frequent the Marylebone area of London. He wheeled all his worldly belongings – plastic bags and bin liners filled with the detritus of his life – around in three supermarket trolleys. He moved them all one at a time around a little route of his own making in a sort of relay of rubbish. It was a seemingly pointless endeavour, a Sisyphean task, that only made sense to him. His belongings were mostly garbage – stuff – that he was carting around from one street to the next. In a metaphorical sense, I had become like him. I had not one but two households full of stuff. I was trying to drag along a broken marriage and several broken adult relationships. I commuted back and forth from Penzance to London in an exhausting search for money to fund a lifestyle which produced more and more debt and less and less happiness. And, as I have said, I had an unthinking adherence to a set of values I inherited rather than created and which made less and less sense to me as the life I had built unravelled.

At the same time all this was happening in my head, three cataclysmic events of the heart coincided in the same year:

- My much loved business partner lost an agonising two year battle with cancer.

- The newest of my ‘this is it, this is the one’ relationships imploded.

- My dad died.

Like the homeless man of Marylebone and Ned in The Swimmer, I was left looking at the broken pieces of my life strewn about. Like Dudley Moore in the film Arthur, I had smashed the ornament and, after a hopeless attempt to fix it, had to admit that this particular thing was ‘a goner’.

Like the character played by Jim Carrey in the film Bruce Almighty, I had been blind to the signs that my life was way off track. I needed to get off the motorway and find a better road, a different route. As all the other people who were on their own motorway sped past me on their journey to whatever destination they were auto-piloting towards, I pulled over and had my midlife crisis. Thank God I did.

What I did is in part 2.