When the going gets tough, the tough go away. My world had collapsed. The death of my business partner and the death of a relationship, both in the same year, catapulted me into crisis. I was emotionally exhausted and had had enough. It was time to take time out. But what to do and where to go? Sitting in the pub opposite my sister’s house, where I had been taking refuge, I had been investigating a ski instructing course for my sons. We’d met a friend of my niece’s who had done it and was working a season on our last holiday to Kitzbuhel. Suddenly it seemed like an option for me. I did some sums on a beer mat. “I could do it”, I heard myself say out loud.

I hadn’t started skiing until I was 25. But I was hooked ever since. We had gone skiing when my sons were old enough, enjoying great holidays all over the Alps with my sister and her children. But going to the mountains once a year for a week wasn’t ever going to turn me into Bode Miller or Franz Klammer. Whereas, enrolling in a six week course to go from zero to qualified ski instructor would catapult my skiing skill into the stratosphere. I would never get there on a couple of lessons every year, but the Ski Instructor Academy in Austria, well, that would be intense but it could transform my enjoyment. And, if I qualified, it came with a job as a full time instructor at a resort of my choice. Which was very appealing because I’d kind of had it with consultancy for a while. Some fresh air and a job doing something simple appealed.

I enrolled and booked my flight to Innsbruck for the beginning of November.

Meantime, I had six months to survive. Back at my place in Cornwall, I was contemplating moving. There were too many morning runs crying in the dark and that lifestyle didn’t appeal so much any more. I needed a solution to jolt myself out of my sadness. One night I sat bolt upright in bed at 4am and said: “Brighton!” Brighton was where I wanted to live. It was seaside (and I do like living by the ocean), but it was lively and near London – two distinct advantages versus the very quiet and very far away location I was based in at the time – and I only needed a place for six months. Brighton would fit the bill very nicely. Penzance is lovely, but we had played it out and it was definitely time to move on. I stayed with a friend in Kemp Town for one night, got up incredibly early the next morning and walked the streets of Brighton, looking in all the estate agents’ windows for a place to live. By 4pm I was on my way back to Cornwall having had an offer accepted on a tiny house in Kemp Street in the North Laines. The next two weeks were busy. I sold off or gave away most of my possessions. Shedding all that stuff was very cathartic: a sofa to a friend, hundreds of books to charity, antique pine furniture went to auction – it would have fetched a fortune in the Portobello Road but went for a song in the local auctioneer house, which was run by a crook. Everything else was packed up ready for the move. I gave notice on the flat, packed all my belongings that were left in a long wheelbase van, held a little farewell drinks one night in June at the Jubilee Pool cafe and the next day, left for Brighton.

16 Kemp Street, North Laines, Brighton

Alverne Hay, Penzance

There was an additional advantage to Brighton which was that my eldest son was coming up there to start at the University of Sussex that September and although my youngest son still had to finish his A levels in Cornwall, he was living with my ex-wife, his mum, and she was looking to leave for pastures new as soon as he was done. So I felt I was just getting out of town slightly ahead of the rest of the family. Maybe I was pre-emptory. I should have been the responsible parent and helped see my second son through his A level year. But to be honest I was pretty broken, and you don’t always either think straight or think selflessly when you are broken.

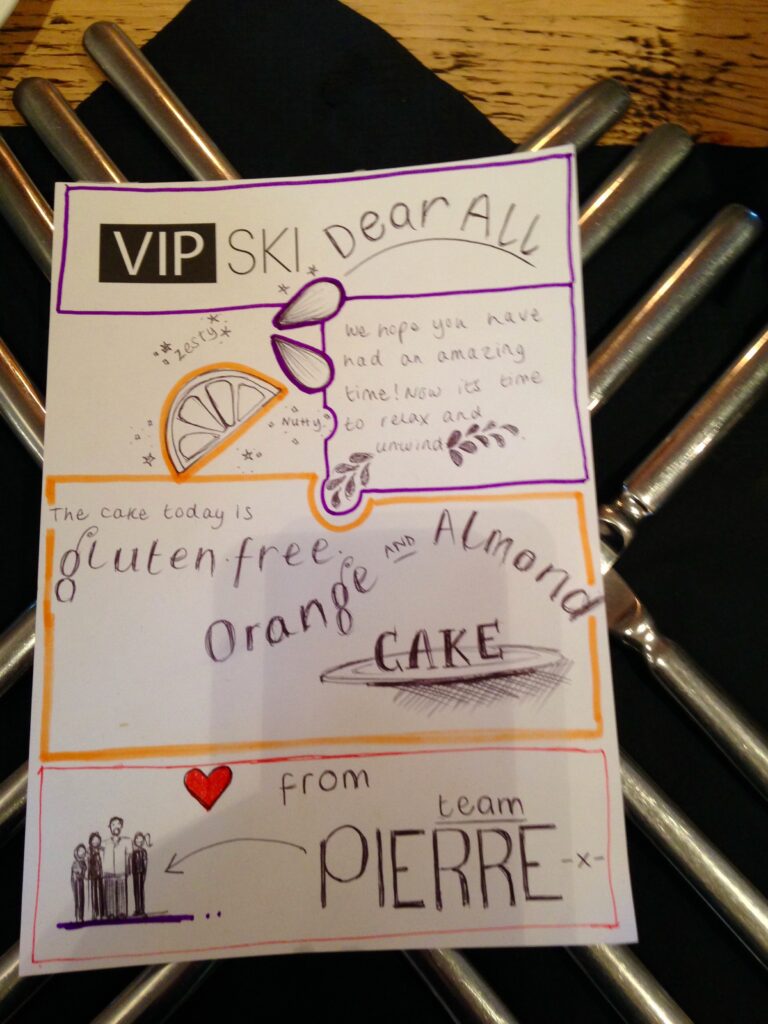

That summer I enrolled on a two week Alpine cookery course – in Milton Keynes. It was run by Mountain Chefs cookery school, which prepared people for chalet work in the winter season. There is a thriving seasonnaire market of mainly young people who want to work in the mountains (this was before Brexit kyboshed all that) and this cookery school trained them up so they could create fine dining dishes for their employers’ guests. My cooking skills had been nil until I separated from my wife. Really. Nil. I cooked a meal on St. Valentine’s day and that was usually from a kit where the ingredients turned up with instructions on how to prepare each dish. I know. Pathetic. Since moving out, I had had to learn to cook for myself and for when the boys came over to stay with me. Surprisingly, I discovered that I loved cooking and the course really moved that along. I also applied for a job with a chalet company – VIP SKI – just in case the instructor job didn’t pan out. I don’t know why I had the prescience to do this but it turned out to be a stroke of genius given what happened.

Panacotta

The cookery course made me proficient in the kitchen and I now had the confidence and skill to make passably good dishes. Getting the position that would allow me to cook in the mountains was the next step.

What the fuck are you doing here? We’ve been drawing straws upstairs to see who should come and interview you. We can’t work out if you’re a spy from our competitors, an undercover journalist or for real. Which is it?

Pip B.

It’s not everyday that ski companies get 49 year old ex advertising executives turning up at their door asking for a job cleaning loos, making beds and washing dishes. The normal candidates are aged 18-24. I was somewhat out of scope. But Pip and I got on like a house on fire from the moment she walked into the room and fired that opening f-bomb at me. Within ten minutes she offered me a job, which I banked, just in case.

Summer ended and autumn gave way to winter. I packed up my belongings, gave back the keys to the house in the Laines and put my stuff in storage. Everything I needed for the ski instructor course was bought and packed and I remember getting on the train from Brighton to Gatwick, with my ski bag and dressed for the mountains, smiling smugly at the besuited, unsmiling, grey commuters thinking “I’ll never have to do what they’re doing again”. That thought made me smile. The week before, I had done my final business meeting at the Barclays Bank tower block in Docklands. Everyone was oohing and ahhing at the view over the City below. My eyes were hankering after a different view. I was tired of man made landscapes. I wanted mountains. And now the mountains was where I was headed.

The office today…and everyday

The ski school for instructors was hard. There were a few older candidates who were rooming together but my room mates were all in their early twenties. I was glad; what’s the point of sticking to your own crowd? What are you going to learn if you just reconfirm your own prejudices? The whole point was to get some different experiences and perspectives. The owners of the school were a Dutchman and a Brit. For six weeks I struggled as my fellow students excelled. As well as relearning everything on the slopes – six hours skiing a day – we had to pass an exam in German. My studies were conducted in an hotel in Kaprun with old school charm and a roaring fire. I called my period in the town my ‘trial by the fire’ and it was. German tied itself in knots in my mouth but I managed to memorise enough of the stock phrases I would need up in the mountains as an instructor. We had lectures on avalanches and sessions in the gym for fitness appraisal. Every day bar Sunday we were up on the Kitzsteinhorn glacier for lessons from our instructors, all of whom had pretty much been born on skis. I went up on Sundays in addition as I needed the practice. In the evenings, we went to the bars of Kaprun and smoked and drank. It was the only time I would be able to use the title ‘schilehrer’, ski instructor, which was the magic password to cheaper drinks and discounted food in the town.

As exam day approached I became less and less sure I would pass and get the coveted Anwerter basic qualification which you need in order to take up your position as an instructor. My season in St. Anton was looking under threat. And to make things even worse, I was getting news from home that my dad’s health had deteriorated fast and he was dying.

We sat the German exam and passed. Then we went outside and the wheels fell off. To pass you must demonstrate your ability in 4 techniques. I passed three but failed my short turns. And that was enough to fail the exam. Ten days later I had another go. And passed my short turns…but failed my long turns. And so on. By now, I was out of time. The bulletins from home were dire and so I returned home to Yorkshire to see my father. I made it just in time, for he died two days after I got back. His life was done. And so, apparently, was my season. I know this sounds callous. But my dad and I had said our goodbyes very deeply a few years earlier when he was going into hospital for an operation they didn’t expect him to survive. We had both said our piece. And, to be honest, it is that moment that I remember him by rather than our last encounter together when he was mildly delirious and confused.

Dad died at the stroke of midnight on Christmas Eve. Timely, given he was an avowed atheist. In the month I stayed, we buried dad and gave him a memorial party at his golf club in Wetherby. After his death, the family dispersed and I was left to look after mum, who was angry with dad for leaving her alone. I reconnected with VIP SKI and told Pip, the woman who had interviewed me, what had happened. She said they had a vacancy in Morzine as a chalet crew member. I accepted and a week later I flew out to Geneva. My season was back on.

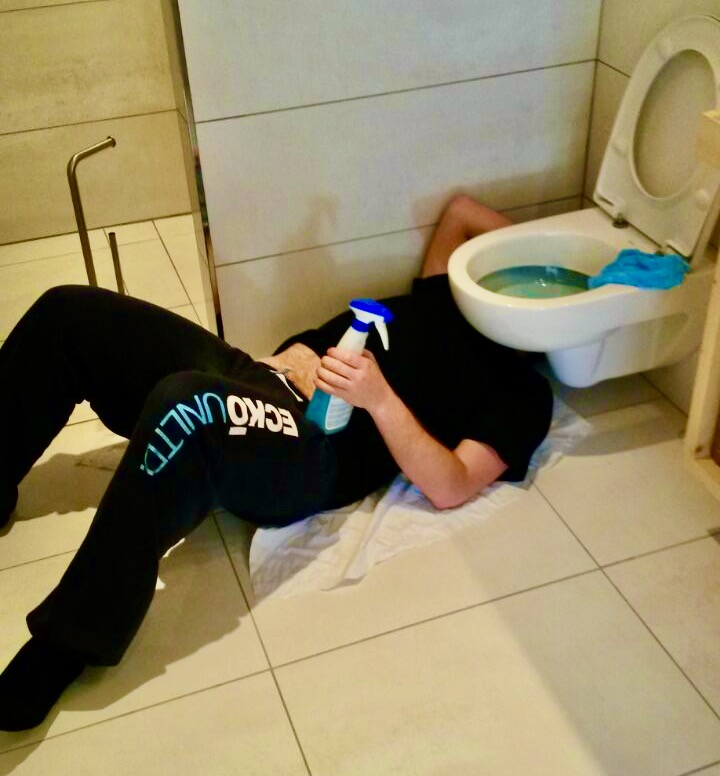

Every nook and cranny is cleaned

Even the inside of the fire is polished

I arrived in Morzine off the coach from Geneva airport along with that week’s resort guests. They were all shown to their chalets. I was shown to my quarters, a windowless wooden cupboard with a bunk bed, a taciturn 18 year old room mate called Harry and the washing machine which the nannies in the flat used day and night. A mile’s walk out of town. It was in at the deep end.

The season had been in progress since December and the rest of the crew – 18-24 – were already hardened seasonnaires. I was put under the wing of Alice and she showed me the ropes on preparing breakfast and dinner and the chalet cleaning regime. A week later I was shipped into the Du Pre chalet to work with two girls, Charlotte and Snowball. They finished my training experience and opened my eyes to the fun aspects of chalet work and play.

Bloodied, I was given my own chalet, Berger (or Budget Berger as the rest of the crew called it as it was the oldest and least glamorous of all the VIP chalets in town), with Harry. Harry was almost completely silent and hopeless with guests. But he could cook. I did the front of house chat, cooked breakfasts and dinner starters, he did loos and bathrooms, the afternoon cake and main courses. We took it in turns to make the puddings and to come back early to work at 5.30pm if there was a kids’ tea to be cooked. We muddled along pretty well, but I wouldn’t describe us as VIP SKI’s Chalet Team Of The Year. We were always the first of the crew to finish every night and we didn’t do the flourishes that other chefs did. But we got great reviews from our guests on the company website every week and we did work very, very hard. There were no complaints.

Luxurious staff quarters

Chalet Du Pre

Alice’s fiefdom & my training ground

After several weeks, you develop what is known as ‘chalet hands’. All the time spent with your hands in hot water cleaning and scrubbing takes its toll and your hands get red and sore. It goes with time, but you do need to look after them with cream of they become very painful. Guests could make you sore, too. They vary. Some nice. Some smug. Some insane. It amused me to listen to their entitled conversations around the dinner table, accommodate their Alpha male behaviour for the first half of the week whilst they are still in work mode, and to observe their relationships. I was staff and therefore effectively invisible, for although you are with them all the time, look after their every need, feed them, bottle wash their baby stuff, recommend restaurants (they don’t understand that none of the crew can afford to eat in any of the places being recommended to the guests) ski schools and ski runs, and you bond with them over the week they are with you, you are still staff. And you have another agenda. To get them out of the chalet as fast as possible in the morning so you can clean quickly and get up the mountain yourself.

The promise

The theory

The practice

Guests tend to follow a fairly predictable pattern and they act their age. The twenty somethings want to get pissed, party and shag. They take aprés ski seriously. They want booze and lots of it. The thirty somethings are all starting families, have young kids and use the nanny service. Having nannies and children in the chalet is a pain in the arse. The mums (never the dads – there is nothing more traditional in sexual stereotypes than Brits on the slopes) are usually a bit tense and always want to heat the infants’ milk or food in the kitchen, so you turn around with an eight inch knife in your hand only to find them right behind you and a centimetre away from hospitalisation. The dads are all corporate thrusters, alpha males, sure of everything and their first question is ‘what’s the wifi code?’ so they can attach to the umbilical code that is the office. And kids means you have to come back from the slopes earlier to do their tea because they usually eat before the main dinner for the adults. The forty and fifty year olds bring teenage children. The latter are more laid back than the former. And the sixty year olds are all old friends or retired ex colleagues. They know what they want and what they are entitled to. All age groups bring their own set of challenges for the common or garden chalet host, but, in the main, the guests just want to have fun and a week of being pampered. I know. I used to be one.

Every week brings ten new guests to my chalet and every week one or more of the party get injured. Usually on the slopes but often just from being pissed. Lots of hassle and paperwork accompanies injury and you’ve got a person confined to the chalet. Which is dull for them and annoying for you. The week follows a pattern. New guests fresh from normal life are still in work mode or London mode, as I called it. They are curt, sometimes rude and very demanding. They burn on a short fuse and anything which isn’t to their liking is immediately cause for complaint. All the free compensatory bottles of Champagne are given out between Sunday and Tuesday. After mid week and the chalet staffs’ day off (Wednesday) the guests’ attitude alters. Whether it’s the lack of being looked after for 24 hours which brings them to their senses and makes them realise how lucky they are, or whether it’s just time passing, decompression from the strains of everyday life and relaxation setting in, you cannot say. But from Thursday to departure on Sunday morning they are as docile as lambs. Which is just as well, because come Sunday, you have a maximum of five hours to get the old lot out and off to the airport, strip the beds, make them all up with fresh linen, clean the bedrooms and bathrooms so they sparkle, clean the public areas top to bottom, make up the fire, menu plan for any new guests who have allergies, freshen all your kitchen and bar stocks, make the welcome cake, ensure the ski passes and skis, boots, poles and other equipment are delivered in chalet and cook a three course dinner for ten hungry people in time for when the new ones arrive. And be ready with a welcoming smile, canapes and a glass of something bubbly.

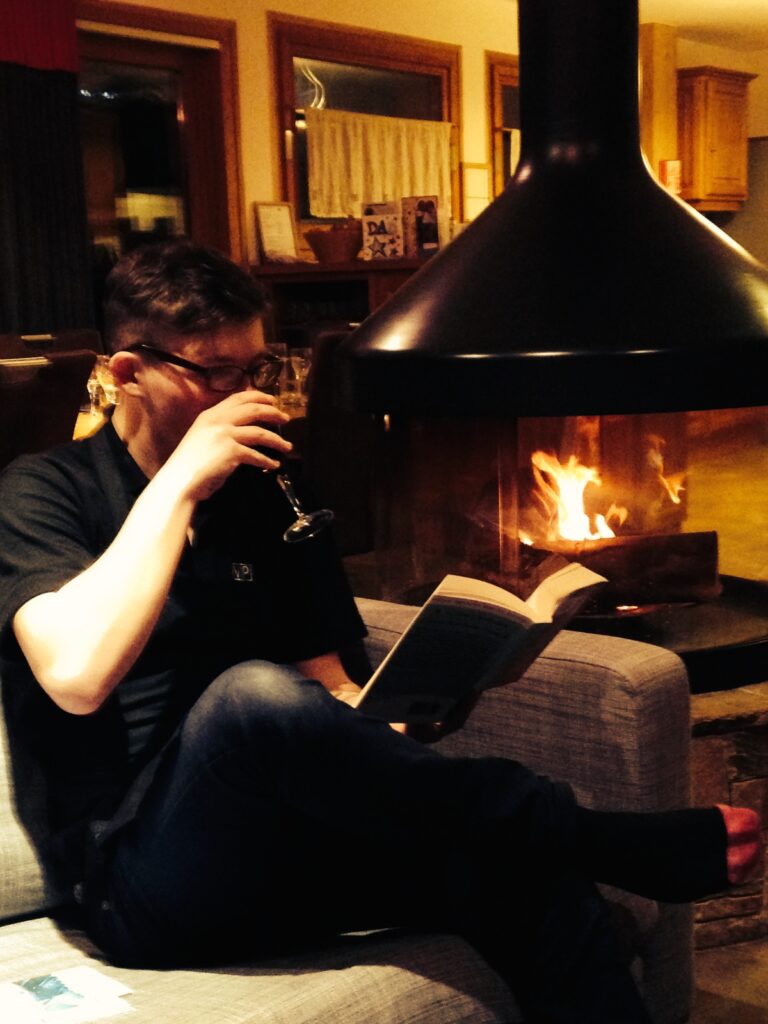

Harry pretending it’s all easy with a glass of wine and a book by the roaring fire

Budget Berger – my chalet for 2013/14 season in Morzine

My new bunkbed – still a mile’s walk from work at 6am

Guest bed – guests think crew sleep in luxury too

There is something incredibly satisfying about all this hard work. Once dinner is on the table and you have cleared it all away, work is done. No taking work home. No unfinished jobs. You clean and cook and tidy away and it’s done for the day. And the result is tangible. Happy, well fed guests and smiles all round. Then off you go to start your own night. You get fit, too. Not just from the skiing every day but also from doing the housework. Bending, stretching, moving all the time, I lost weight easily and felt much the fittest I had for years. And I looked healthier – that ski tan made me realise how pale and old my friends looked when a few of them came out to see me. Hanging out with the twenty-something year old crew was also energising. You just have to go at their pace and they hit the lifestyle hard. Dancing and drinking the night away until 2am and then up at 6am to walk to the chalet for another day’s work. Every day. Every night. It is exhausting, but you get into the rhythm and so it becomes normal and also a lot of fun. I felt rejuvenated. And the crew adopted me as their ‘daddy’. They were the nicest, loveliest crowd of people and I couldn’t have wished for a more perfect group to make me feel both welcome and alive again.

Unlike some of the guests. The week of my 50th birthday, we had a chalet full of ten ex Shell executives. My, they were smug. They were quite sniffy about things but I remember the night before my birthday, which fell on our day off thank God. They had heard it was my birthday the next day and summoned me over to the area by the fire where they were having their pre-dinner drinks.

“We hear it’s your 50th birthday tomorrow?” said the group spokesman.

“Yes, that’s right”, I replied.

“Well, happy birthday!” continued the spokesman, and at that, they all raised their glasses to me and chorussed

‘HAPPY BIRTHDAY!’.

No glass of Champagne was proffered to me. Nothing was offered at all. Just the toast. I said thankyou and went back to the kitchen, laughing to myself. Some people just don’t get it, do they? Harry and I drank our stolen Champagne in the back room behind the kitchen, out of sight from the guests. My birthday was waiting for me up the mountain. And with people who were a lot more fun than these stuffed shirts.

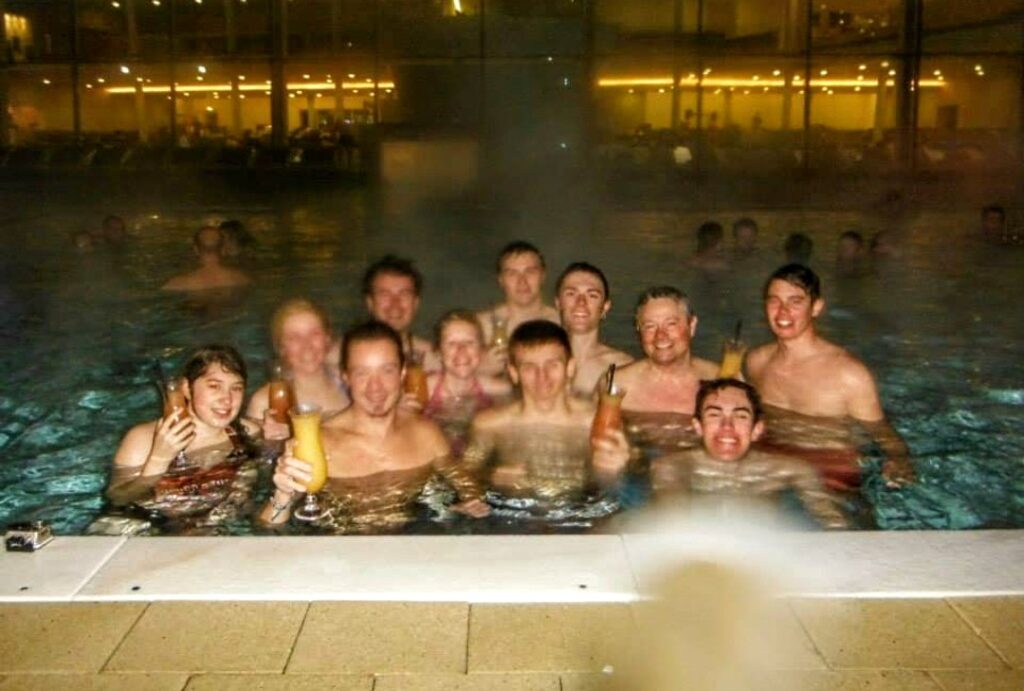

50th birthday up the mountain with the finest bunch of people I could have wished for to help me celebrate

Chalet crews look for any excuse to have a good time and days off are very precious. My birthday gave the crew an excuse for a party and we kicked off the day with a traditional British breakfast fry up in our accommodation and a big spliff, which was my present. My room mates had decorated the room with bunting and balloons and once we were fed, we all headed up the mountain to the rendezvous point. They set about building a bar out of snow and the beers and Champagne were laid out on top. Everyone came and it was wonderful day. I had only known these people for five weeks but I couldn’t think of a better bunch of friends to share my landmark birthday with, and that day is forever emblazoned in my memory. It was spent, effectively, in the company of virtual strangers. Yet I couldn’t have felt more appreciated or more acknowledged. When I rang Josh, he laughed “it’s the wrong way around, dad! I should be getting pissed and high up on a mountain, but you are!”. A year later, he joined me in Meribel for his own first season.

Pulferized

Big birthday breakfast with Phil, Dan, Harry, Pia and Alice

The season wore on. You think in weeks – week twelve, week seventeen, tweek wenty three and so on. Counting down until the season is done. It was like my university years trip to Boston in 1984: all immensely hard work but brilliant times. It was just the antidote to the misery and heartache of the previous few years. I came alive again and I wanted more of this feeling. Near the end of the season, a very old schoolfriend generously paid for a minibus to bring me over for the day from Morzine to Val d’Isere. Once my crew mates heard of this extravagance, we put together a party to travel over with me for the day. Setting off at 5am we arrived in time for the opening of the ski lifts. I went off to be with my mate and his family and they all went off and got merrily pissed (on the slopes). This day was my thank you to them for the season. We all ended up in the Folie Douce, which involved table dancing and revelry after my old friend had departed. He couldn’t appreciate the excitement and was acting his age. I wasn’t and didn’t have the emotional constraints any more. I remember a girl friend of my crew mates saying I most certainly didn’t appear to be fifty. I was not acting my age and I was glad of it. It tells on your face. I hadn’t smiled so much in a decade.

Katie H in Val

Neil & me at La Folie Douce

I’m the Daddy

Dawn start to Val d’Isere – Snowball’s mate, Ben, Pulfer, Pilgrim, Me, Rupert, Snowball, Katie Pigg

The rest of the season eeked its way out and we dreaded the day when it would all end. They say that in a season you exist in a little bubble up that mountain. It is easy to think that no other worlds exist. The routine keeps you going and it is such fun. But it must all come to an end, and that end was fast approaching.

A crew which sleeps together…

My masseur

Best friend Beth

Cake sale – Pilgrim, Dan, Ben and Alice

Aperol time

High jinx in the back room

Contentment

Happiness

Cooking

After the last guests had departed and the snow begins to melt, the chalets are deep cleaned and shut down one by one. The crew end up in one chalet after cleaning their own accommodation. I had occasional bouts of depression and I was still wounded from the break up of my relationship with a woman who had not been good for me, but who had probably been necessary. I returned to the UK to nothing. No home. No significant other. No clue what I wanted to do other than do another season. I remember panicking on the morning I was rejoining my colleagues at my firm and I called my remaining business partner to tell him I wanted to go back to the mountains. That day we had an all team meeting and I asked everyone what they had done over the last six months whilst I was away. No one had done anything of note. Whereas I had had the time of my life, made loads of new friends, put over a thousand dishes on the table, gained new found respect for twenty year olds, many of whom I counted as friends now, learnt to ski well and spent my time in humble work and in some of the best scenery in the world. I felt alienated from them all – like anyone who has enjoyed an intense experience does when they return to the people who know them but who can never understand what they have been through. That day ‘back at the office’ was a flattening experience. To get over it, I booked myself into an ayahuasca retreat for three, mind blowing days. (You can read about this experience in another blog called ‘The Trip’.) If you’re going to have a mid-life crisis, better do it wholeheartedly, eh?

I determined not to re-enter corporate world so I sold my shares back to the company, which enabled my co-owner to offer share options to potential new people and keep the enterprise going. The money kept me going through and so, after visiting my mum, clearing the marital home in Penzance with my children and enjoying time with them at our annual family gathering in Suffolk, I spent the rest of August sailing in the Med. An old schoolfriend who is a good sailor had invited me to go with him on a yacht around the Ionian Islands for a fortnight and the week before I had been offered a week’s sailing around the Turquoise Coast of Turkey by Rupert, one of my fellow crew members from Morzine. Rupert had a boat. (Of course he did.)

Reader, I went.

Rupert & Beth sunset swim

The boat

Captain at the helm

Port

Shore leave

Restaurant accessible by boat only

Storm clouds

Both these trips were utterly cathartic. Mountains and sea are amazing remedies for damaged souls, and my soul was most certainly damaged. In amongst all the good times there was a lot of processing going on and I was with people who loved me and cared about me, which made me feel safe. And able to value, or rather re-value myself.

Kissing Ithaca – home at last

Odysseus

Clarity

Under sail

My writing room

Ithaca off the port beam

A little light relief in the form of the ice bucket challenge (which was sweeping all before it at the time) courtesy of my fellow sailors around the Ionian Sea:

https://www.facebook.com/david.kean.3557/videos/10152645769047236/

During the rest of the summer I lived from the back of my car. I was an itinerant. I had a brief liaison with a lovely woman in Eastbourne and we had fun that summer. But it was not a great love and I was on the rebound, so it was doomed. Once I went off for my second winter season, the relationship ran out of steam. You could tell we were doomed because I kept going off to be with my ski chums over the summer. I wasn’t capable of looking after anyone or being with anyone for keeps just yet. I went to festivals – I was invited to work on a coffee stall at The Secret Garden Party in Cambridgeshire and I went to Bestival on the Isle of Wight and saw Elton John play his first festival. Like me, he was so impressed he asked from the stage:

Festival elephant

Porky & Bess

Sparkled up for summer

Neptune

Hats

G&Ts at Henley

Dressing for the Stewards’ Enclosure

Henley happiness

“Why haven’t I done one of these before?!”

Elton John at Bestival 2014

It was a sentiment I shared. This was so much fun, why hadn’t I done it before?

Three amigos making cold brew

One port-a-loo opened onto a secret field of sunflowers

I also went as a guest of one of my ski chums to Henley Regatta, where a few of us re-gathered to re-create the atmosphere from our time together. These are all classic mid-life crisis things to do. And you know what? There’s a reason for that: they’re all brilliant fun and festivals create an atmosphere and a vibe you just don’t get anywhere else, least of all in mid-life land suburbia. Festivals help you believe in a better tomorrow. But unless you’re a lifelong muso or an habitué of festivals, people over a certain age just dismiss them as a young person’s thing. Which is wrong. Ask any band – their average age is way north of the average festival goer but they’re still rocking. Older people, middle aged people just put all these experiences in the ‘not for us’ box. They ask the wrong question. They ask “why?” instead of “why not?”. Why not is a better question. It is the question of choice for midlife crisees.

My second winter was unlike my first. It was traumatic and I went into myself. I was working for the same firm but this time as resort manager in Meribel. The crew and I never really gelled and I ended up on my own for much of the time. The job sucked – being a chalet chef is much more entertaining. Being a manager is just lots of admin and sorting out hassle – of which there is tonnes. Yes, you get better accommodation, but I only skied for forty days instead of a hundred. A lot of soul searching occurred in my little attic flat over the following months and my mood was as dark as the winter nights. I was seeking resolution to all my demons and trying to put that catastrophic relationship from the year before (the one I was rebounding from) to rest. It didn’t help that she was also working in Meribel. The threat of running into her was around every corner. And around a few corners I did run into her. I just had to deal with it.

Eventually, when Spring came to the mountains and the butterflies re-appeared, it felt as if I was emerging from my own cocoon. I had realised that I needed to reground myself after my flights of fancy. Not to lose the self-love and lessons of the two winters away, but to find a home and start to rebuild. Meribel was my own personal winter of discontent, but on the other side of it, I emerged more whole and ready for new life. It came much quicker than I could have ever hoped in the form of Tatiana, who is my muse and my saviour. We make each other’s and our own dreams come true. Together. And happiness, as someone once said, is a thing best shared.

Meribel church

The view from my room

The mist in the valley and the mountains on top – a metaphore for the mind clearing that went on in the mountains

A naughty dip in the hot tubs end of season

Where the madness happened – my cocoon in Meribel

The beating heart of the Meribel operation – every Tuesday evening I would call the next week’s guest to give them the snow report. We always lied. Whatever it was, they only wanted to hear it was due a dump the night before they arrived

I am grateful to the mountains that they gave me the time and space to heal myself. If I had my time over I’d do it all again. There were very lonely times but it was a joy to have Josh with me for a few weeks both in Val d’Isere and in Meribel that second season. His company saved me several times. And Sam stayed with me a week, too, and was eventually able to pass the Anwerter exam that I had failed a few years later. They both got their seasons in the snow. They have done their travelling, too – had much more of an Indiana Jones early adulthood than I ever did. And, for their sake, I am so glad they have.

What have I learnt? That being grounded is important, but so is flying the bounds of Earth. That we are all on an Odyssey of our own and that to resign ourselves to that fate, especially when the path home is hard and fraught with trial and woe, is the wisdom life teaches us. That signs are there for a reason and should be heeded. That the Gods laugh at your plans and a partner that can be relied upon is a rarity. That we put too much emphasis on achieving and performing and have our values upside down all too often. That to show love is important and you show it by listening and hearing and seeing the other person not by giving them trinkets instead of attention. That you need to cherish those you love but not at the expense of cherishing yourself. That friendship can be found in the strangest places and faces. That it is necessary to be courageous in order to thrive. That dreams are for following and timidity is dangerous – ‘our doubts are traitors and make us lose the good we oft might win by fearing to attempt’ (Measure for measure). That it is okay to let go the riverbank and that the water will hold you up and carry you along. Even if that water happens to be frozen. That crises are very necessary and the best way to grow and become wiser and kinder and more forgiving of oneself and others. And that a mid-life crisis is not something to be feared or run away from or merely survived, but is instead, quite literally, a lifetime opportunity to take back your life. It is a blessing but not all of us have the courage to embrace its challenge. The ride is terrifying and elating, enervating and energising and on the other side is the freedom to be exactly who you were always meant to be.

Life visibly collapsed

Sad in Goa

Road to recovery

Morzine 2014