There was a body in the bath. A dead body. A dead woman’s body. The water had drained out and the man who stood looking at the body in the bath, who had spent the night in the hotel room where the body in the bath lay, had no recollection at all of the previous night. What to do? Call the front desk? Dial 999? No. Call the guv’nor. He’d know what to do.

He called the guv’nor. The body was dealt with. The incident was handled. The post mortem established that the body in the bath, the guv’nor’s secretary, had had an epileptic fit and drowned in what had been a full bath. Whilst her lover, he without the memory of that previous evening, was passed out on the bed, drunk. As usual.

The drunk on the bed with the body in the bath was a well known art director at one of the world’s pre-eminent advertising agencies. He was terrified he had done something to the girl in the bath and that gaol lay ahead. But the incident was smoothed over. And he never forgot the debt he owed to the guv’nor. So much so, that when the guv’nor left the agency to start his own shop, the copywriter followed him without a murmur. Loyalty counts.

The same man, the same guv’nor. Different story. This time the copywriter had penned what was to become a masterpiece of the art of advertising – think boy on a bike on a hill, breadbasket mounted on the bike. You know. The guv’nor told the copywriter that he needn’t be present in the room for the presentation of the idea to the client.

But I want to be. I want him to appreciate the idea fully.

I can handle all that. You trust me don’t you?

Yes, but this is the best work I’ve done. I want to present it.

Well, you can’t.

Come on. This is me you’re talking to. Let me present it.

Yes. This is you I’m talking to.

Ah. you’re worried I’ll be drunk and screw it all up.

It’s not just that.

I won’t. I swear. This is so important to me. To the agency.

As I said. It’s not just that.

Well what is it then?

Yes, it’s the drink. And the presentation is at 4pm. You’ll be well gone by then.

I won’t, I swear.

It’s not just that.

Then what else is bothering you?

The client has a large…proboscis. I know you. In your state you won’t be able to prevent yourself.

Guv. I’m only interested in selling the work. I’ll be good as gold.

The guv’nor relented. 4pm came. And went. No copywriter. The meeting began. Fifteen minutes in, the copywriter stumbled in. Drunk. Fumbling his way from the door to the client, the copywriter stretched out his right hand and pinched the client’s nose between his forefinger and index finger and shook it. Vigorously.

How do you do?

Giggled the copywriter and he turned for the door, harumphing with glee. The Guv’nor smoothed it over, the work was sold and the campaign went down in the annals of adland history.

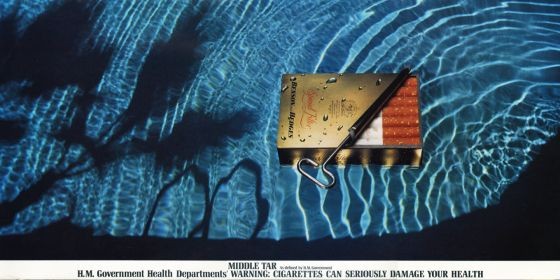

Swimming Pool – I remember seeing it at the cinema 40+ years ago. It was that spectacular

These are the stories that make the TV series Mad Men look innocent. Advertising in the 70s and 80s is legendary. The industry was chockablock with characters, bad behaviour, ego, excess. For my generation and the one before, this was our understanding of how business was done. No wonder the rest of the world of business, serious businesses like banking, insurance, manufacturing, engineering, groceries and retail regarded advertising as light entertainment. And yet, if ever you needed proof that bright, happy, motivated people who are creative can thrive and produce world class work in an environment that other, more sober types, would regard as frivolous, irresponsible and chaotic, London’s ad scene in this period proved it.

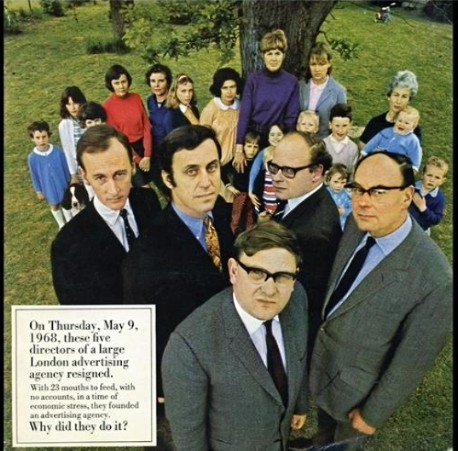

London Adland was born in the 1960s. Yes, there were old stalwart agencies before then, but they were pale copies of their American counterparts on Madison Avenue, NYC. They were square, sober, ex officer class, suit-led (that is, business led rather than creative led) operations that produced formulaic, respectable advertising that was indistinct and anodyne. In the 1960s, galvanised by the revolution wrought in America by Bill Bernbach at his eponymous agency, Doyle, Dane, Bernbach, the London agency Collett Dickenson Pearce appeared. And everything changed.

Collett’s was the crucible of creative talent that spawned multiple agency start ups, launched the careers of some of Britain’s most famous film directors and broke every rule in the gentlemen’s club of advertising that had hitherto held sway. It produced advertising that was iconoclastic. Funny. Advertising which treated the viewer or reader as intelligent and an active participant in the work rather than as a passive consumer with no imagination or brain. And it used the new mass medium of television to make its clients’ brands famous.

Collett’s spawned Saatchi & Saatchi, Lowe-Howard-Spink and a host of other famous agencies who are subscribed to the same philosophy – that the work came first. The creative department was the heart of the agency and everyone else’s job was to sell the creative department’s output come hell or high water. For example, John Salmon, the Chairman of Collett’s, once told a client that he didn’t tell them how to make their bread so they shouldn’t tell him how to make advertising. In those days, when adland was at the height of its pomp, that attitude worked. Now, the industry is more timid and clients more knowledgable. And, you could argue, the work has suffered as a result.

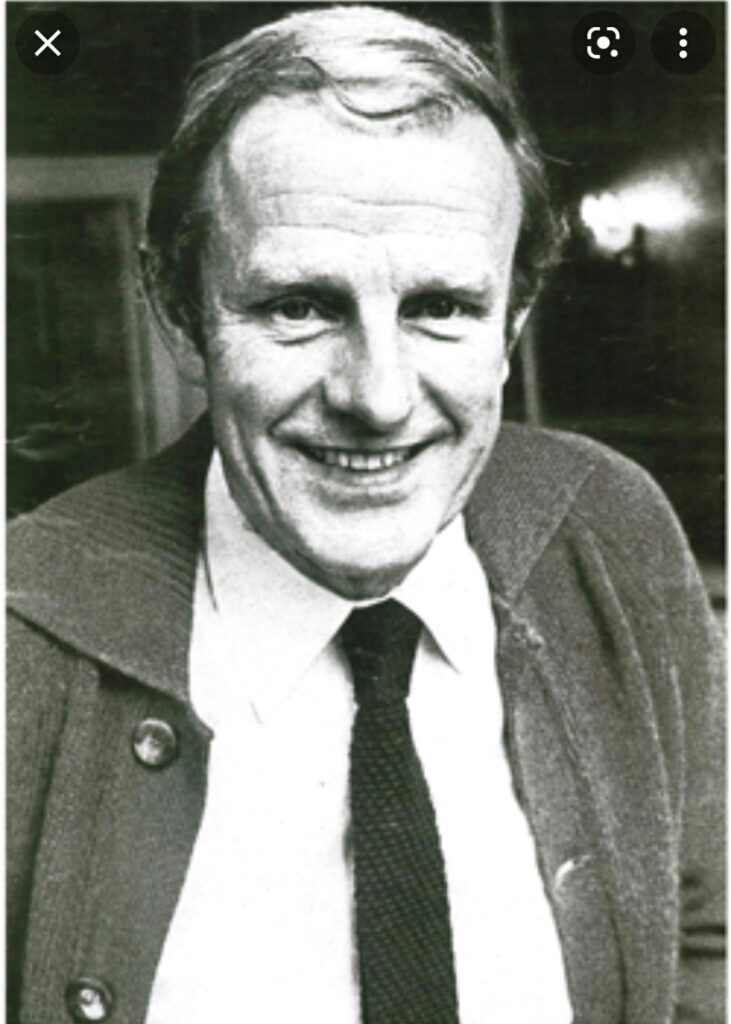

If you were a suit – the go between from agency to client and client to agency – working in this new generation of agencies, your job was to sell the creative work. And if you didn’t, well, God help you. As an old boss of mine recounted from his days at Gold Greenlees Trott, he returned from an unsuccessful attempt to sell a creative idea to his client and went to see Dave Trott, the creative director, to explain what had happened. As my old boss – then a junior account manager – knocked on the doorframe of Trott’s office, the irascible and fierce creative director – looked up from his desk where he was penning his next masterpiece, fixed a stare on the nervous account man and said:

Are you sure you’re ready for this meeting?

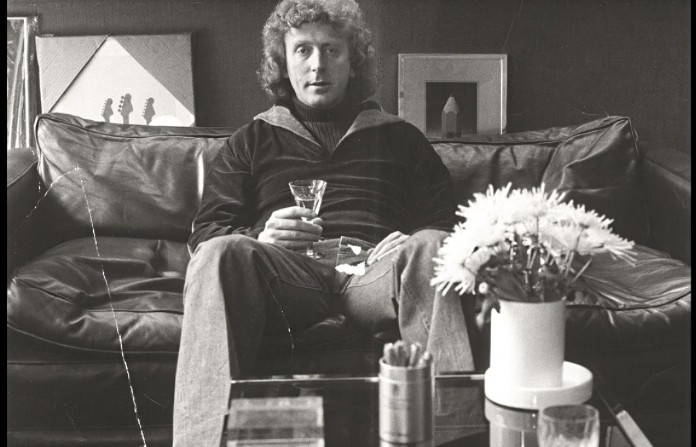

Dave Trott, enfant terrible and creative supremo

My old boss slunk away. He went back to the client and sold the work. Must try harder was the lesson. I guess it was a matter of who you feared the most, your client or your creative director.

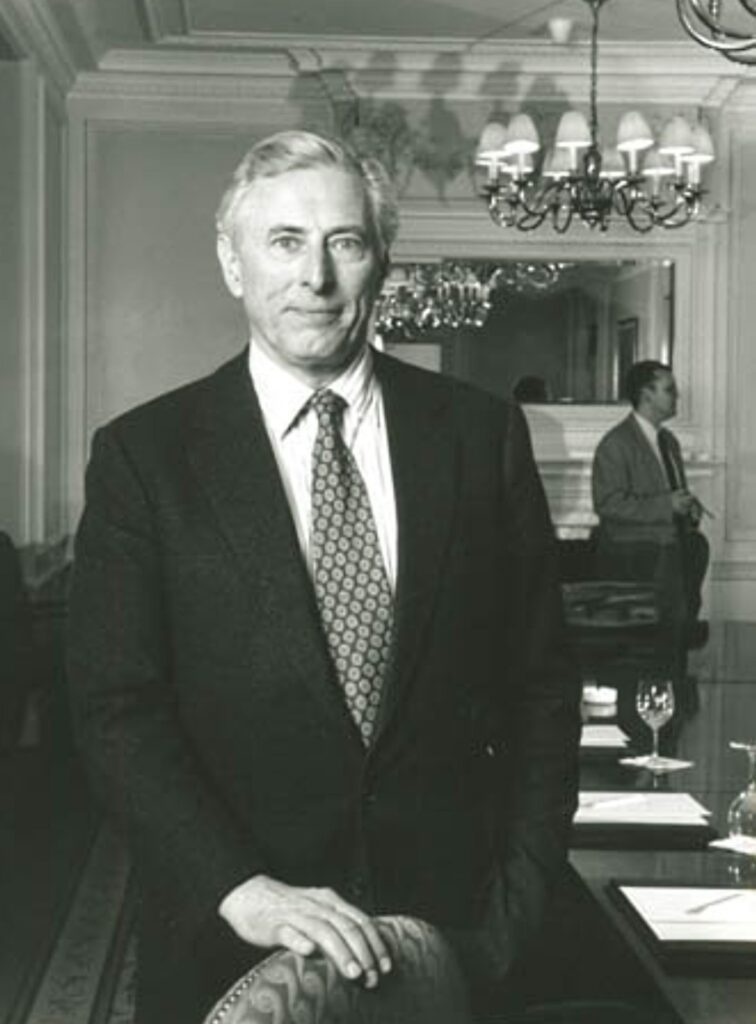

In spite of the seeming chaos and general anarchy that characterised agency life in these years, it was underpinned by iron discipline. The play pen of creativity thrived because it was always answerable to a larger than life character who had the total confidence of the creative department – someone they all trusted absolutely not only to sell their outlandish output but who also spurred them on to be even better and even braver. At Collett’s it was Frank Lowe. Lowe was to creatives what Che Guevera was to international revolutionaries. One account man – who went on to become an award winning and utterly hilarious creative – was nicknamed ‘Shabby’. Shabby was a Chelsea FC fan and was walking towards Stamford Bridge to watch them play Manchester United. He was dressed in loon pants and eating chips out of a box as he strolled along. Out of the corner of his eye he saw a chauffeur driven limo slow down and match his walking speed on the other side of the road. The rear window lowered half way and Shabby could make out the distinctive permed hair and face of his new boss, Frank Lowe. Frank was gesticulating and saying something but Shabby couldn’t hear the words over the noise of the street and the fans walking and chanting their way to the ground. Being of an naturally optimistic predisposition, Shabby assumed that Frank had recognised his newest employee and was waving to him across the street.

Come Monday morning. SHbby’s desk phone rings. “Could you come to Mr. Lowe’s office straight away please?”. It wasn’t a question. Shabby straightened his tie and ran a hand through his 1970s style shoulder length hair and went up to the fifteenth floor.

Frank burst out of his office.

Don’t ever let me see you eating in public whilst walking down the street again. It’s slovenly and reflects terribly on the agency. You’re damn lucky I’m not firing you.”

With that, Frank turned on his heels, stomped back into his office and slammed the door.

And Shabby had thought Frank was waving a cheery “hello”.

Years later, when I worked at Lowe Howard-Spink, frank’s agency in Knightsbridge, I was in very early one morning. In those days, in the hours before reception or switchboard turned up for work, if someone called the agency, it switched to the night bell – anyone who heard it was supposed to pick it up. I did.

Where’s my fucking car?

I recognised the voice immediately.

Where are you, Sir Frank (he had a Knighthood by then)?

There was a tirade about how he was at Arrivals and there was no-fucking-body to fucking greet him and where was Alan (the driver, presumably) and a whole series of expletives which went on and on. “Do you know who I am?”, I asked. There was a stunned silence and then a gruff “No!”, as if it was an affront to his status to know which of his underlings he was speaking to (or that they should not immediately know who he was, even though he didn’t say so when I picked up the phone.)

Good

Me

I said, and put down the phone.

Which showed more presence of mind than the hapless creative director who opened his front door to two removal men asking him “where do you want the fireplace?”

“What fireplace?”

“It says ‘ere, ” started the foreman, reading from his notes “one Italian Renaissance marble fireplace surround, C15th, from Mr. Lowe’s villa in Glebe Place, to be delivered to a Mr. W at this address.”

“Oh. Well you’d better bring it in. ” The men did.

“There’s an invoice ‘ere, an all” continued the foreman when the fireplace had been deposited inside.

“Invoice?” enquired the creative director.

“Yeah, fifteen thousand nicker. ‘Ere you go.” And he thrust it in Mr. W’s hand and departed.

Ripple dissolve to a dinner party at Frank’s a few weeks before and to our hapless creative director, a guest, making admiring comments about the elegant fireplace as it adorned the room in the villa where drinks were being served. He had been taken at face value and paid the price for his sycophancy.

There was another account man at Collett’s, suave, polished, ramrod straight, who, it was said, didn’t know how to turn right on entering an aeroplane.

There was a creative team who bet another account man that they could be taken out for lunch every working day for an entire year. They won.

And a creative who passed out in the back of a black London cab after a particularly heavy night out on the town. The cabbie was taking him home but her passed out so the driver circled the M25 all night until the morning when the passenger came to and could tell him where he wished to be deposited. The taxi fare was picked up by company expenses.

At my alma mater, Allen, Brady and Marsh, things were, as they say in Thailand, “same, same…but different.” Peter Marsh was the rod of iron there. I saw him only once. Well, I didn’t exactly see him. I saw the swish of his green Inverness cape and walking cane as they disappeared into the lift one evening. This was a man of Osimandian ego and pomposity. A man who sat on a golden throne behind his desk with a life sized portrait of himself commemorated in oils behind the throne. A man who delighted in showing off. He once pushed this too far with Lord Hanson, whose newly acquired Imperial Tobacco firm retained ABM as its agency. During the small talk between the two titans, Marsh asked Hanson if he had ever seen Marsh’s new, white, stucco fronted mansion on his journeys from his London HQ to Imperial Tobacco in Bristol.

I don’t know. What colour’s the roof?

Lord H.

Marsh was humbled.

In my days at the agency, the account managers walked around with shoulder holsters and replica Colt 45s and in the days when the agency was so successful it occupied three different buildings, you could say you were going to a meeting in one building over the street and disappear into the pub all afternoon and no one would be any the wiser – provided your meeting partner from the other building said that they had a meeting in your building at the same time. This sort of behaviour was tolerated by the management for too long. We once taped one of my friends to a chair with wheels, put a bin on his head and pushed him into the lift. Apparently, when the lift opened with our friend on the chair inside it, the then managing director – who was waiting for the lift – tut tuttted, got in and pressed the ground floor button to go home. My friend spent an uncomfortable journey travelling down in silence for six floors. When the agency had hemorrhaged all its greatest and most famous clients and the chauffeurs outnumbered the strategic planners, the writing was on the wall. ABM closed its doors for ever and with its demise, the 1980s truly came to an end.

Advertising in London began to sober up. But then, of course, the largesse shifted to other markets in other parts of the world. Russia and Asia, whilst not the creative power houses of London, certainly knew about largesse.