During the pandemic we have watched lots of films but the TV screen can never replicate the experience of plush, velveteen seats, the sense of anticipation, the pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa papa-paa, pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-paaaaaaa-pa of the Pearl and Dean ads and the trailers and the slurp of your drink before the curtains pull back and the entertainment begins. Cinema is where life plays out in microcosm and in glorious Technicolor; it is where a thousand relationships started and simmered, a place of excitement and intensity. It is the place of celluloid dreams. It is where most of us started our love affair with larger-than-life, with heroes, heroines, villains, outlaws and the extraordinariness of ordinary people’s stories. With the ride of fear, love, hate, loathing, vengeance and laughter that feels more real at the flicks than anywhere else. Cinema is a wonder-world and I miss it.

The flicks, the pictures, the movies. Two or so hours of transport away from the cares of the world. The medium of choice for exploring the Universe, both the internal and the external ones. A mini holiday from life. Only in London do you still get the vast, double tiered auditoria of old. The Upper Circle has been consigned to yesteryear as more and more cinemas under financial threat in the 1980s and 90s either converted into Bingo Halls or converted to multiplexes – one building housing multiple screen in smallish theatre style rooms. The grandeur died and cinema became pedestrian. But there are some theatres which have gone the other way and found a niche audience who value the grandeur of old and who will pay through the nose for the experience and sense of occasion that is cinema’s golden age. These are the places I venerate – collectively known as the Art House cinemas. The Curzon in Mayfair and Soho, the Duke of York and Komedia in Brighton, the Electric in Notting Hill.

The Electric Cinema, Notting Hill

There are some films that, from the moment the curtain goes back and the main feature begins, produce a smile of anticipated joy on the faces of the audience. Chocolat, starring Johnny Depp and Juliet Binoche, for example. Raiders of the Lost Ark for another – even my dad sat up with joy as we were all introduced to Harrison Ford’s trilby wearing, whip-wielding archaeologist. Here was a hero who arrived on screen and achieved instant God-like status. My father was less enthusiastic four years later when I returned from University sans job and, in answer to his question “what do you want to be?”, I answered ‘Indiana Jones’. And some first experienced on the big screen – The Godfather and Apocalypse Now to name my favourite two – I eagerly seek out whenever they are re-released into a selected cinema for another outing beyond the confines of Amazon Prime and the flat screen TV.

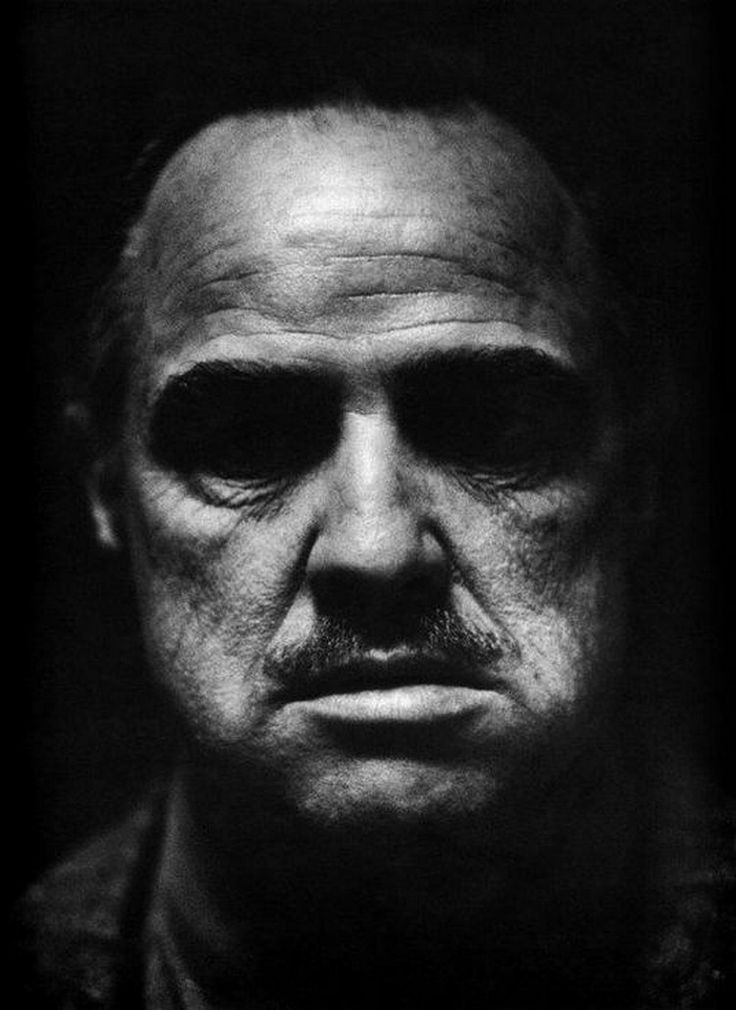

Michael Corleone – Godfather II

Where Death comes to cry – the soulless Mafia Don played by Marlon Brando

Coppola’s epic of the Vietnam War

Someday this war’s going to be over…Colonel Kilgore in Vietnam

I remember my parents driving us all the way to Skipton’s Plaza cinema in the 1970s to go and watch Gone With The Wind, which hadn’t been in cinemas for decades. As the first big motion picture filmed all in colour, you can imagine the effect Scarlett O’Hara and Rhett Butler had on a pre war audience used to the silver screen. I remember not being bowled over in the way my parents had been. Which is sad because it really is an epic film and a magnificent story. I suspect I was too young and did not have the life experience to relate to the relationships playing out in front of my eyes. Maybe there’s a reason every film has an official certification for the ages allowed to view it.

There are other films, the ones which are niche and only get a screening in the rarified atmosphere of the Art House cinemas, which are best described as hard work, but ultimately rewarding. These films are not mere entertainments. They are often heavy and depressing but make a point and send you out into the world feeling virtuous. And, if you are lucky, enlightened. Virtuous for having sat through the cinematic equivalent of a session at the gym. Enlightened because they usually carry a message – about what it is to be human, or to make you aware of a particular cause or to show you what the world is like or was like for others not like you. Your reward is the feeling that you have done something worthwhile, something noble and spiritually aggrandising, rather than merely spectated an entertainment.

When I lived in Cornwall, the Penzance Film Club hired Screen 2 of the illustriously named Savoy Cinema every Monday evening through the winter season. They showed ‘art house’ films. The films were apparently chosen by a poll of the membership, but whoever and however they were chosen, the obscurity of the subject matter and the chewing-through-a-bowl-of-dry-muesli sensation of watching them definitely put them in the category of ‘hard work but ultimately rewarding’. They were not light entertainment, nor meant to be, on a dark early January evening.

On one infamous occasion, they ran a film – black and white, naturally – of a bearded, tramp-like man on a raft polling himself very slowly across a pond. After twenty minutes of this, we had had enough – not least because there was seemingly no soundtrack. We popped out and asked the manager if there was something wrong with the equipment and he assured us that no, nothing was wrong – the film was silent. We left anyway, defeated by a film that was just hard work and joyless without any redemptive qualities. When we got home, we looked up the name of the film to find that far from it being a silent film, the score and the soundtrack were integral reasons for the critical acclaim this particular piece of art had attracted.

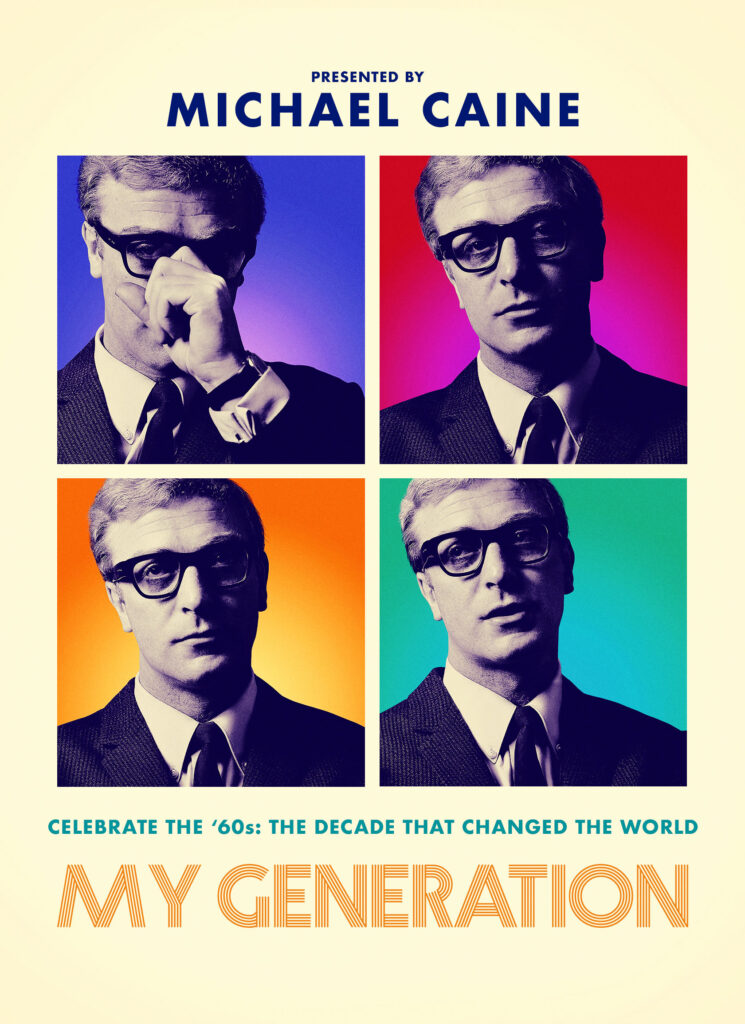

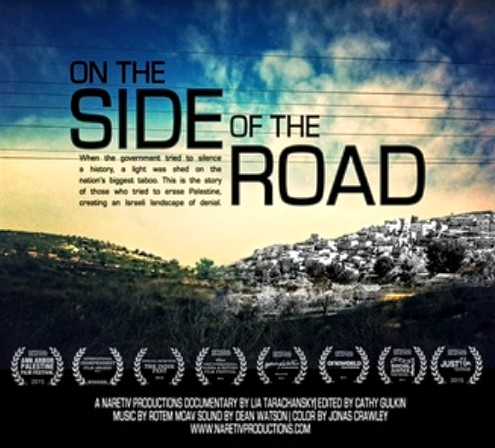

Which just about sums up the ambiguous relationship we have with art house cinema: no one dare complain because no one knows if the thing is meant to be like this or not. It is like the Emperor’s new clothes – it takes a mischievous mind to point and laugh. Everyone else just sits there in silent awe, even though they are really being taken for a ride. In 2013 I was taken by a rich client to a fundraiser – a special showing of On the Side Of the Road, the Israeli Lia Tarachansky’s polemic about Jewish settlements depriving Palestinian West Bank residents of their homelands. The audience was all Arab bankers’ wives and Americans. My client was Jewish. It was thought provoking and very moving. But it was surreal to be sitting in the expensive Pullman seats sipping Champagne watching people’s homes being bulldozed in a powerful piece of political propaganda. One must suffer for art, it seems.

Art House cinema is often a bit like wading through a book you aren’t enjoying but in a room you absolutely love. At least you can look at the walls and enjoy the atmosphere. Some Art House films are like Catch 22 or Kerouac’s On The Road. However hard I try to feel the brilliance on every page and however much I remind myself that Bob Dylan credited Kerouac’s classic with changing his life because he ‘understood freedom’, I just find these books pretentious and irritating. I have sat through many cinematic equivalents and the hours I have spent in darkened Art House cinemas only occasionally repay the investment. But once in a while, they do. And when they do, the experience makes all the other dross worth the effort.

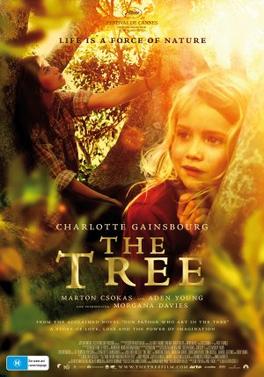

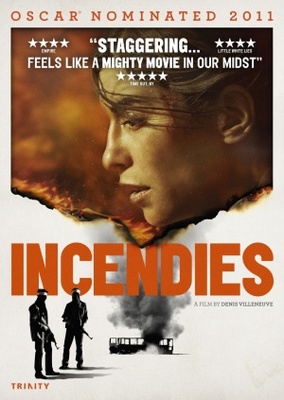

The Tree, an Australian-French collaboration, closed the 2010 Cannes Film Festival and received a seven minute standing ovation. It’s haunting title track, The Tree by Grégoire Hetzel, played on my ipod on repeat as I stared mournfully out of the Penzance to London Express – both up and down the line – for months. It was a beautiful film, and although it didn’t enhance my already melancholic mood the winter of 2011 (that was more to do with being in a relationship with a brittle depressive than the music), it was a beautiful story. And Incendies also sticks in the mind, but as an horrifically violent film which I would only see once. Once is enough. It’s brutalist message doesn’t bear repetition – every frame is carved on my retina – and it helps you realise how people can end up being so cruel to one another and how even a mother’s love cannot redeem a soul beyond repair.

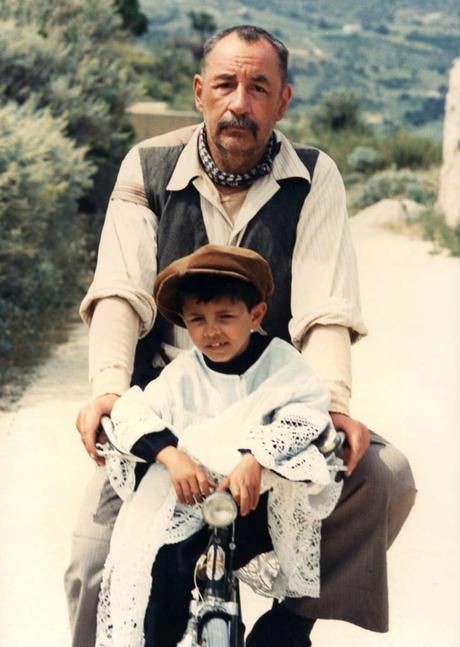

Alfredo and Toto

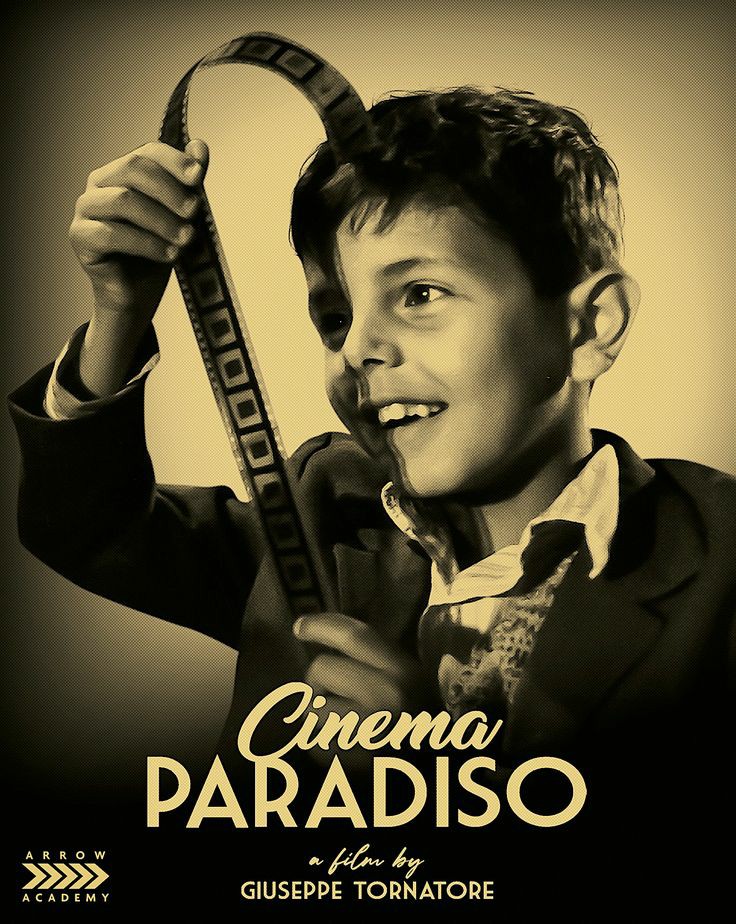

All the naughty bits

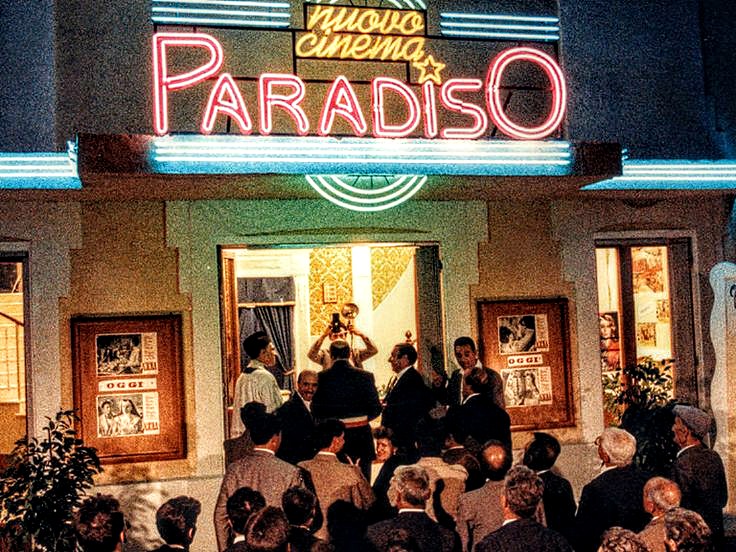

The re-opening

A mother’s love

By contrast, there have been films which have made the miserable weather outside feel like Californian sunshine. The experience of watching Cinema Paradiso is one such. I beamed and wept from beginning to end, soaking up the impish Toto and the avuncular Alfredo. The poignancy of the hero’s mother keeping his room as it was when he left Sicily for the mainland – her love so beautifully captured in the actress’s eyes and touch of her hand on her son’s. The burning celluloid that blinded Alfredo when Toto dragged him from the fire in the projection room. The spliced together kissing scenes left by Alfredo as a parting gift to the grown up Toto. The scene where they turn the projection outside to let the people watch the film from boats in the harbour. The petty squabbles, rivalries, hatreds, snobbery, love, sex and spitting contemptuously on the audience members from the more expensive upper circle that characterised every performance at the Paradiso. The awful finality of the demolition of an institution that represented the soul of the village and the story of the lives wrapped up in it. It was like revisiting childhood.

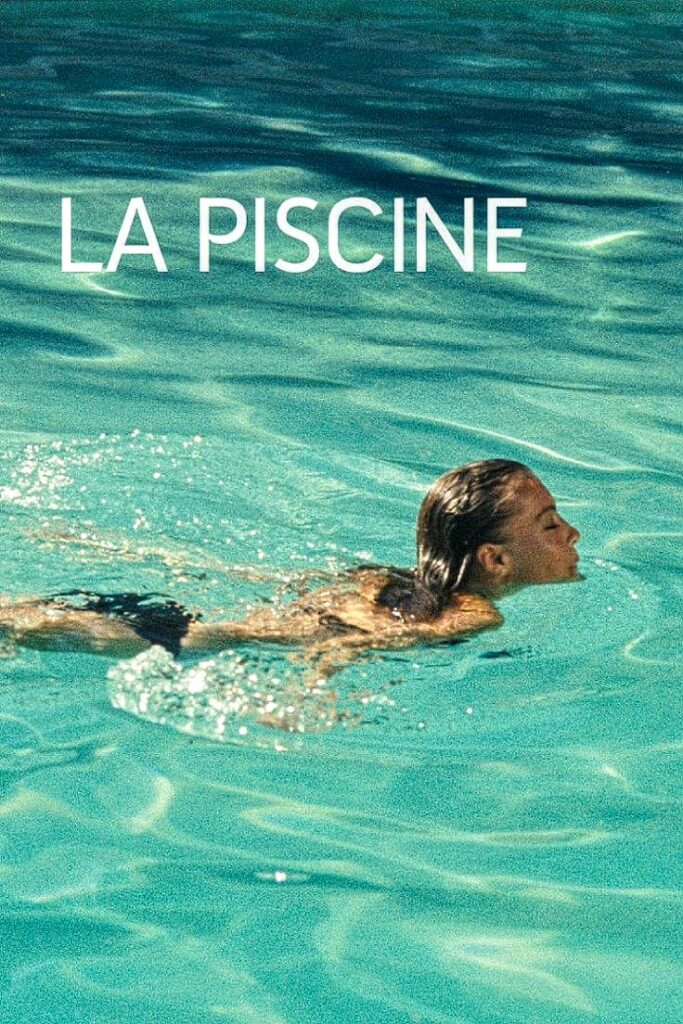

Cinema Paradiso set me off on a love affair with Italian and French films. In my mid-teens at boarding school in York, I snuck off and skived games to go see Alain Delon in Le Samurai and La Piscine. I even snuck in to see Emmanuelle II (the soundtrack for which is still the most erotic of scores) even though I was under age. No one seemed to mind then, even though the cinema was dotted with the rain coat brigade. Maybe I was showing early promise for that fate. The York Odeon was where I first gawped open mouthed at Colonel Kilgore in Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam tour de force and discovered I shared a sense of humour with Woody Allen. It was also where, aged seventeen, I walked in to watch Warren Beaty’s Oscar winning biopic about journalist Jack Reed, author of Ten Days That Shook The World, as a recalcitrant public schoolboy looking for a cause and emerged three and a half hours later as a Marxist and wannabe war correspondent. Cause found. The power of the big screen.

Eugene O’Neill, Louise Bryant and Jack Reed

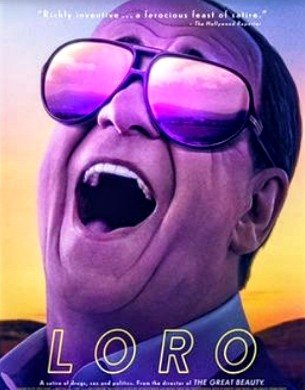

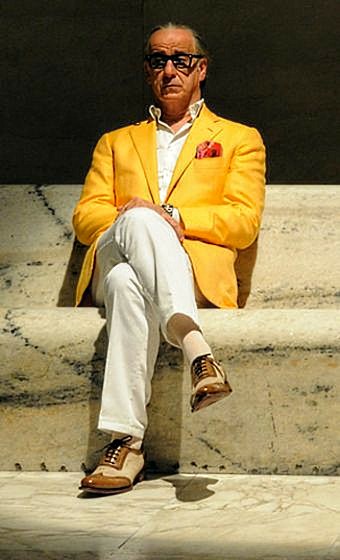

As I say, I have a penchant for Italian films. Especially those by the director Paolo Sorrentino. The Great Beauty and Loro in particular, both of which star the actor Toni Servillo. They manage to be profound without being pretentious. And Massimo Troilli’s gentle masterpiece, Il Postino. These directors seem to be able to capture different aspects of the human condition from lovely, interesting angles – a writer who is disappointed in himself and has pursued pleasure over craft until he is set back on the path by an encounter with a sharp tongued incisive nun who is rumoured to have the gift of prophesy; the bottomless ambition and wily salesmanship of Berlusconi, Prime Minister of Italy. A figure reviled as much as revered. And the quiet, plodding patience of the postman, a man who in spite of seeing himself as insignificant, protects the man who inflicts the hurt he feels when his kindness is not repaid by the great exiled poet Neruda. These are all great cinema, great examples of the art.

The Great Beauty

I hope they open cinemas soon. Or there will be none left to open. We need an escape from this normality and the cinema will weave that magic better than any other medium. It’s time to leave the house and re-enter the Art House. The hard work is done. Let’s hope it is ultimately rewarding.