York city centre. The Odeon cinema, row 20, seat 17. 3pm. Wednesday 27th February, 1980. The afternoon matinee is showing the 1971 subtitled classic Le Samourai, starring Alain Delon. I light up my Gitanes – you could do that then, inside, I mean – inhale deeply and exhale conspicuously, mimicking the eponymous assassin on screen. I should be freezing to death on the rugby field back at school, a mile and a world away, exposed to an icy wind that hasn’t stopped blowing since it started in Siberia. Instead I am warm, an anonymous head amongst another half dozen or so heads visible above the velour seats in this cavernous auditorium. The usher – they had them then – is bored and entertaining himself by using his torch as a gun, twizzling it in the dark like a badass killer from the Wild West. Saddo, I think. I go back to my reverie. I am bunking off games, missing in action (or inaction given my usual lack of contact with the ball) playing hooky. I have escaped the perils of the outdoors and I am totally at home in this dark, sensorially overwhelming place, in a make believe universe, feeling artsy, intelligent, a cut above. My 15 year old self is alive with pretentiousness.

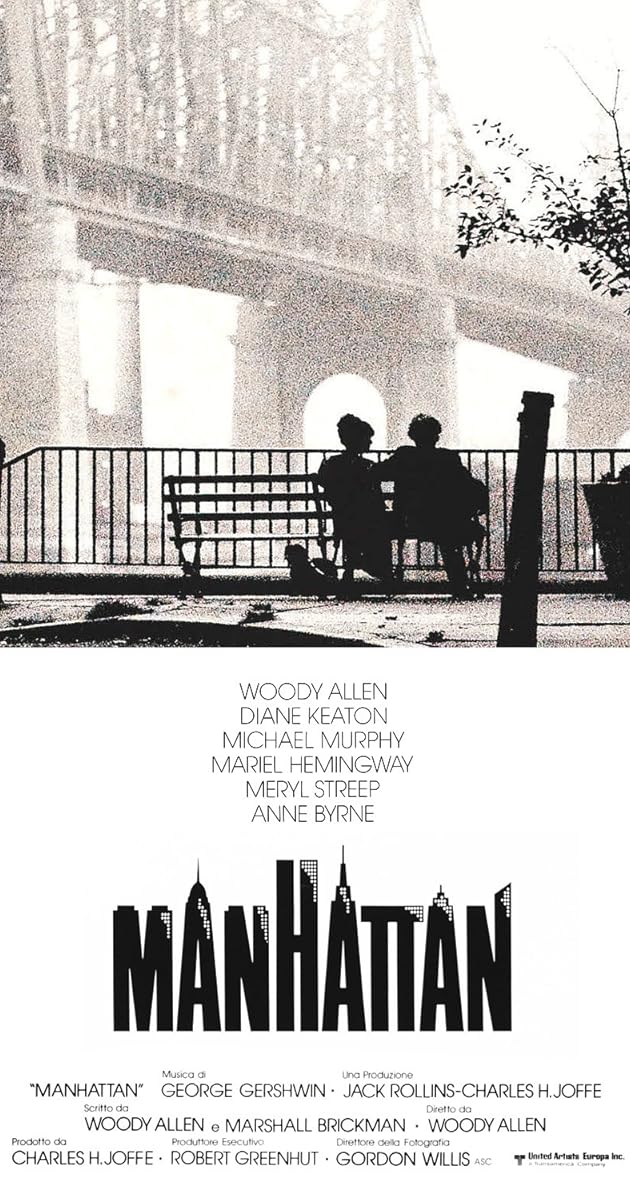

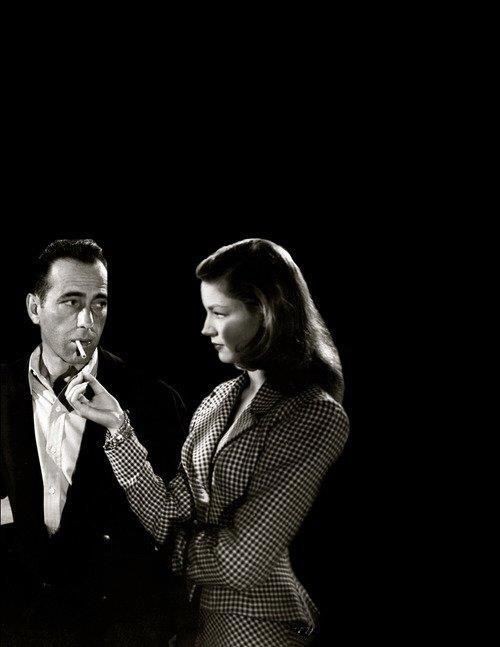

How did I get here? The final straw was standing out on the wing in a freezing field at Hymers College in Hull, a school out on the eastern wing of northern England, as horizontal rain needled into my legs and my hands turned blue. The ball never made it past the outside centre, who was a Death or Glory boy. As he buried his fifth try right next to the corner flag with his characteristic leaping dive and stood, ruddy with exertion, basking in the ruffled-hair plaudits of our team mates, I sullenly slunk back to my position ready for the kick off and silently vowed that this would be my last appearance on the field of play. From now on, I would not be keeping company with mere mortals, but with the heroes of my imagination: the aforementioned Monsieur Delon, Bogart and Bacall, the celluloid fantasy that was Mariel Hemingway in Woody Allen’s ‘Manhatten‘. With Vito Corleone. With Martin Sheen, traveling up the Mekong Delta to terminate Colonel Kurt’s command ‘with extreme prejudice’. They would be my team mates from now on.

To be honest, by slinking off to the cinema, I was doing us all a favour. I was neither use nor ornament on the rugby pitch, and I doubt my team mates even noticed I wasn’t on the wing anymore. The hole my absence left was more penetrating in attack than I had ever been and was less of a risk in defence. You never really knew whose side I was on – my actions on the pitch being as much to the advantage of our opposition as to my own side at least half the time. I had caused the under 16s committed Christian team coach to wash his hands of me, Pontius Pilot style, and even to curse (under his breath) at my lack of love for getting dirty. My parents were more interested in my academic progress than my sporting prowess – they had had their fill of standing on bitterly cold touchlines supporting my two older brothers. And Inside Centre Glory Boy certainly didn’t need me. In three years on the wing, the ball only made it past him once to me and I scored my only try of an ignominious career before hanging up my boots for good. No one would miss me. I was safe and safer in the cinema.

In here I was cocooned from the cold. I hated the cold and the whole rigmarole of changing rooms, physical larking about, spraying each other with Deep Heat, getting muddy and being the last line of defence as the opposition team’s Goliath bore down on me and my home try line. I bitterly resented having to throw myself under his studded heels. So I didn’t (once caught, twice shy). Instead, I opted for the gullible defender strategy – he feigned left and I went with him towards the touchline, only for him to cut inside, accelerate and steam past me. I altered course and got a hand on him, but too late – he got past me. I perfected the look of disappointment and frustration that I had been bettered. I was fooling no one. Certainly not when it happened for the four thousand, seven hundred and fifty-first time. I mean, how gullbile can one man be? It was not a piece of acting that would have convinced even the half dozen sports refugees in the matinee performance.

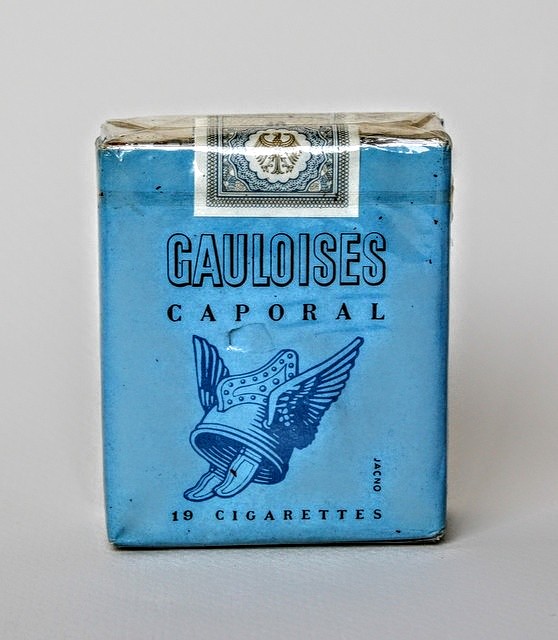

My education in film continued uninterrupted through O levels (GCSE) and A levels. I was an avid student and diligent. I never missed a film at the Odeon matinee performances. ‘Apocalypse Now’. ‘The Godfather’. ‘Annie Hall’. ‘Bananas’. ‘Love and Death’. ‘Play it again, Sam.’ (Yes, there is a lot of Woody Allen – who knew back then? And they are still very funny films, if you like neuroticism. And I did and still do.) Plus all the oldies: ‘The 39 steps’. ‘The Big Sleep’. And all the arty, subtitled classics from France and Czechoslovakia. And through all of them, I chain smoked Gitanes and Gauloises to the point of feeling sick. Every cigarette ignited with my prized, brass, Philip Marlowe-esque, GI standard issue Zippo lighter. When I left the cinema, I pulled the collar of my specially bought Crombie three quarter length overcoat up against the rainy wind and tipped my Trilby hat brim down to cover my eyes. Hunkered against the weather, I lit another Gitanes and slouched back to school, watching for trouble all the way, as any good Samourai would.

These were happy days. I had three years of cinema going and it educated me in the art form. I am still transported to magical kingdoms when I walk into the darkness to find my seat. The whole feel of the cinema. The plush curtains. The screen. The Pearl and Dean:”pa…pa..pa…pa…pa…pa…pa…papapaaaa…pa!” The trailers. The curtains pushing back a little further at each end to widen the screen ready for the main feature. It is magical. And nowadays, I have grown to love rugby. I love it. The game. The tournaments. The atmosphere. The physical effort. The camaraderie. The plays. The tussle. Even the glory boy dives. Yes, I love every aspect of the game. On the silver screen or watched from the safety of row 20, seat 17 in the stands. Some habits never die.