I love the Saatchi Gallery. It used to be on the Southbank but it is now housed in the Old Duke of York’s old HQ at the Sloane Square end of Chelsea’s King’s Road. But in both locations I have seen two exhibits which both delighted and horrified – and both dealt with power. The first was a Chapman brothers extravaganza: Fucking Hell. I took Sam and Josh to see it when they were about 9 and 7 respectively – nine glass cases, like big fish tanks, filled with small scale models of Nazis, skeletons and ghoulish subjects of torture creating a landscape of chaos, the opposite of divinity, nauseatingly detailed, sadistically imaginative and intricate in their invention. Like Auschwitz but without the efficiency. More akin to the drunk, circus-pastiche barbarism of the Einsatzgruppe in the Russian film “Come and see”. Each grotesque figure adds to the chaos but most sinister of all is the tiny figure of Adolf Hitler painting a landscape on his artist’s easel, oblivious to all around him even though he is the progenitor of the entire, macabre, Dante-esque Hell. Depicted as the chronicler of the dystopian vision in paint it is like the creative process in reverse: it seems that his brushes are producing the living landscape rather than recording it.

Sam and Josh were transfixed and found it fascinating. Each vitrine was crammed with spectacle and there was so much detail of horror. The Damian Hurst shark in formaldehyde also attracted their attention, as did the other Chapman brothers exhibit of life sized sculptures of seemingly innocent children who had phalluses for noses and vaginas for mouths. The Chapman brothers, for me, are geniuses, if uncomfortable. They enjoy tempting you in and then smashing you in the face for your sin.

The other exceptional art memory from the Saatchi was Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s “Old people’s home” (2008) which took up the entire basement gallery. Comprising 13 hyperrealist sculptures of elderly world leaders such as Yasser Arafat of the PLO, Fidel Castro of Cuba, Archbishop Makarios of Cyprus and Leonid Brezhnev of the USSR, the figures moved around the room in electric wheelchairs. The wheelchairs had sensors so they would bumb harmlessly into one another in their random journey around the floorspace and then deflect on to a new course. It was a brilliant depiction of the seemingly powerful rendered utterly harmless, even pathetic and vulnerable. Menacing historical figures reduced to impotence. The display was transfixing as well as funny.

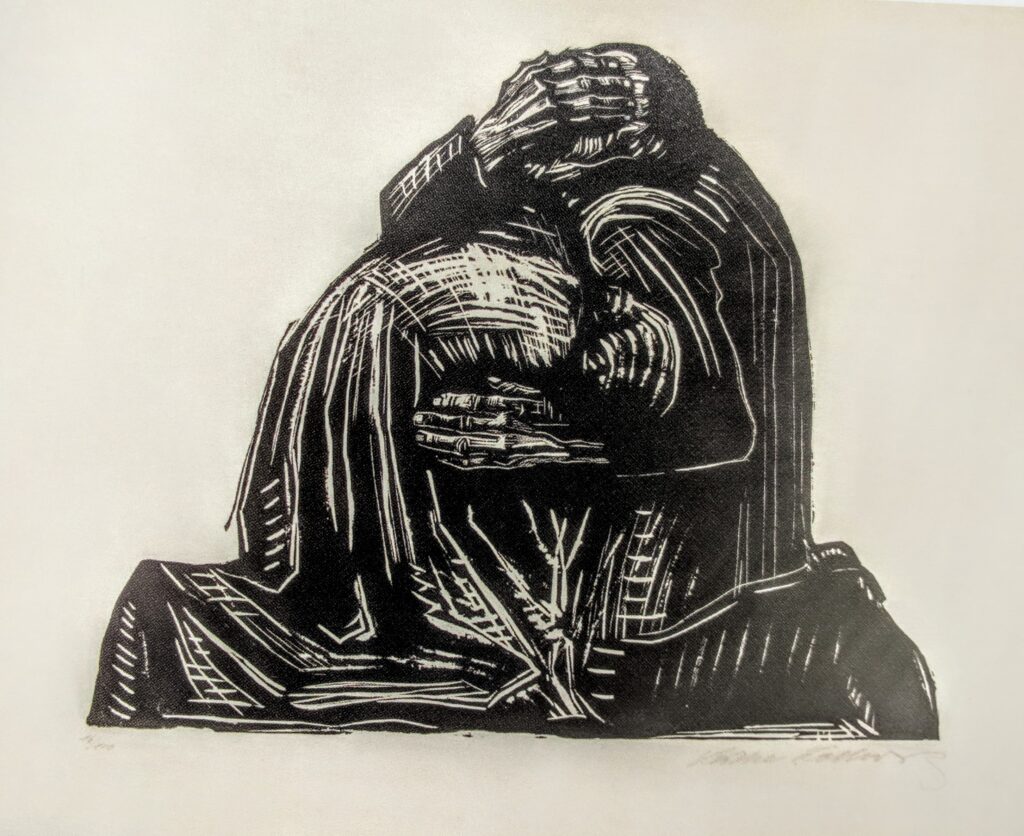

The Saatchi is hit and miss but it is always worth a visit. Whenever I am in the vicinity I always go in. If you get lucky, you hit gold like the two exhibits above. And art such as this, that delivers a gut punch, makes a point on a visceral level as well as intellectual. It is both arresting and memorable. And whilst it is always a joyous feast for the eyes and heart to visit the National or the Tate galleries and to stare at the Turners, at Van Gogh, at Blake and Velasquez, it is the work that effects you in the guts which makes a lasting impression and actually makes you think. Don McCullin’s extraordinary photography in the industrial North of England and in Biafra at the Tate Britain. The simple lino cut of a grieving mother and father embracing in a way where it is possible to see it is two individuals but who are so entwined in their loss that they seem to merge into one, hope draining picture of utter despair. The sun in the great turbine hall at Tate Modern.

The most pungently impactful was Mark Wallinger’s dramatic recreation of Brian Haw’s Parliament Square protest State Britain, displayed at Tate Britain in 2007. State Britain consisted of a meticulous reconstruction of over 600 weather-beaten banners, photographs, peace flags and messages from well-wishers that had been amassed by Haw over five years. Haw began his protest against the economic sanctions in Iraq in June 2001, and remained opposite the Palace of Westminster until 23 May 2006 following the passing by Parliament of the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act, which prohibited unauthorised demonstrations within a one kilometre radius of Parliament Square. The majority of Haw’s protest was removed. Taken literally, the edge of this exclusion zone bisected the Tate Britain art gallery. Wallinger marked a line on the floor of the gallery positioning State Britain half inside and half outside the border. As a piece of protest art, pointing out the awful irony of legitimate protest being outlawed in the very square in London which is sacred to democracy and by the very institution which is supposed to enshrine the individual’s right to free speech in this country, this piece is incredibly articulate. Conceptually and politically brilliant, artistically it is very difficult viewing – many of the photographs displayed by Haw depict the atrocious and sickening effects of war munitions on babies, small children and civilians caught up in war. This is war, guts and all, and it is truly vile. There is no sanitisation, nor should there be. This is not PR puff or flattering portraiture. This type of work exposes the menace of politicians, of war and of neglecting our responsibility to think and to speak out. And isn’t that the real point of art? To provoke our reason and emotions enough to prompt our action?