I come from a relatively short line of posh folk. We’re not really posh. More West Riding posh rather than North Riding posh. North Riding posh is proper posh: fields, tweed, estates, dogs, horses, clapped out Volvos, icy cold bedrooms, LandRovers, family portraits all the way up the oak panelled hall staircase. Mud. Guns. Fresh air. Fishing rods. Holidays in Scotland and Suffolk. Eccentricity.

West Riding is people who still need to be near work where work is industrial, not agricultural. Entrepreneurs. Second generation industrial family businesses – textiles, engine parts, chain manufacturers, shampoo magnates. Private dentists. Sharp suits from Brills in Mooretown (not country togs from Allens in Harrogate). The tang of a Yorkshire accent. Conspicuous displays of wealth – lions rampant at the wrought iron gates of their new build mansions, swimming pools, repro furniture (all bought, none inherited) and, in the 70s, the latest Jaguar.

I remember a workmate of mine reminiscing about his early teen years in 1970s Milton Keynes. He was smiling at his own recollections of those days and reeling off experiences, musical references, activities, descriptions of his school and food that I had absolutely no similar parallels for – he may as well have been describing a childhood in another country.

He was describing a childhood in another country. His childhood was perfectly normal, where both parents worked, holidays happened once a year, food was unbothered by The Galloping Gourmet or M&S avocado pears, school was a bog standard comprehensive, music was The Clash or The Jam and Saturdays were spent in the shopping centre hanging out at McDonald’s and WH Smith.

To help understand how these worlds were so different, when they both collided – which they did at university – a girlfriend of mine, when quizzed about her exposure to normal people by our new working class chums (sic), caused gales of incredulous laughter when she referred to them as ‘the lower orders’. And it became a running joke that we thought they all lived, rather quaintly, off tick (credit) at the local shop, like some cheeky, strike-a-light cockneys from a Dickensian landscape. A friend of ours saw a photo of me around this time. He was a Scouser. Done very well. Had a spot of bother with the police as a lad. And he described my face as ‘very punchable’. It was. And it was punched at university. But that’s another story.

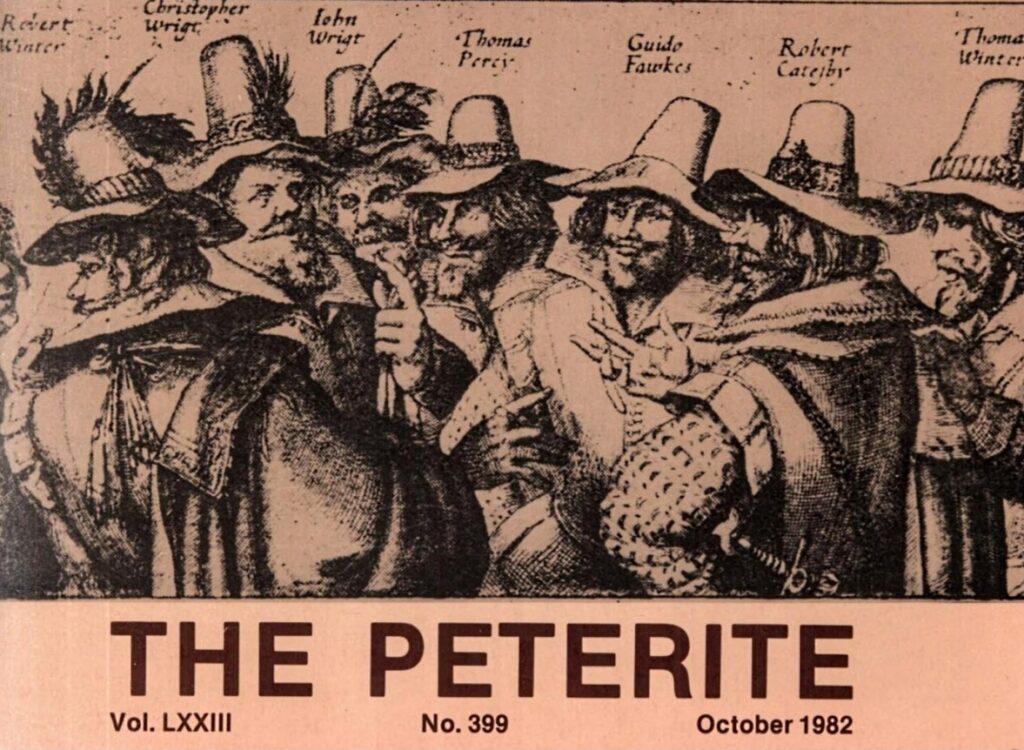

My school was founded in 627AD. No, that’s not a misprint. It had just celebrated its 1,350th birthday when I arrived at it. The school motto was ‘Super antiquas vias’ – along ancient paths. It wasn’t overly progressive. Some of the dormitories were decked out in the original furniture. Well, it felt like that. Our most famous old boy was one Guido Fawkes. Come the 5th November every year, whilst the rest of England was making merry burning effigies of the man who symbolised Catholic revolt against persecution by the government and who tried to blow up Parliament with gunpowder, we alone did not celebrate the night. We simply didn’t burn old boys.

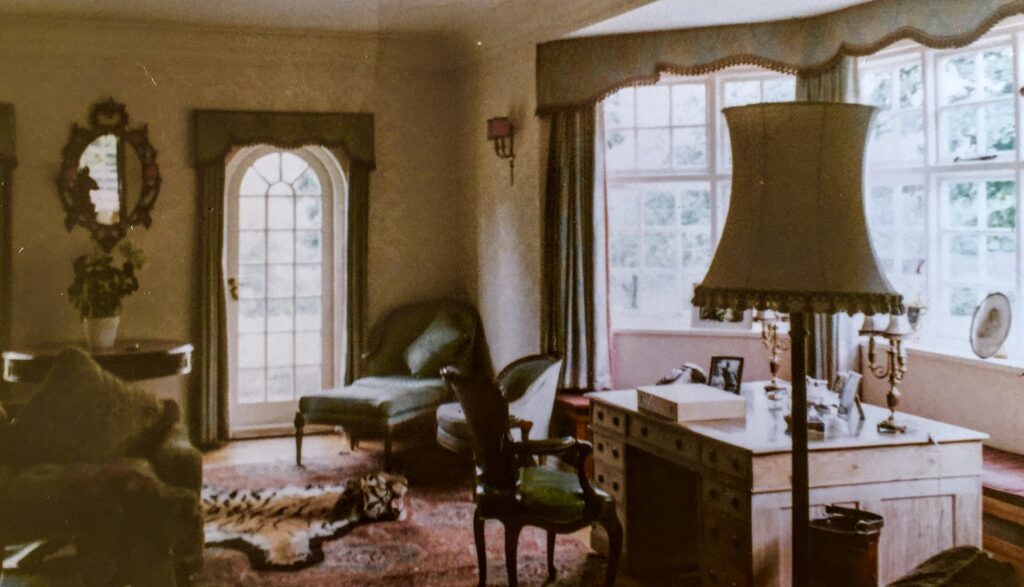

It wasn’t just school that was different. My home was different. Technically, it was a four bedroom semi. Technically. But it wasn’t really. When my wife – a Soviet girl (ah, the irony) – asked to see a picture of where I lived from 1969-1986, I showed her a Georgian Manor house, draped in Virginia Creeper, eight foot high windows, acres of roof and a tennis court all surrounded by a gravel driveway, neatly mowed lawns, tall oak trees, a little cottage, other outbuildings and a stable block, all at the end of a 800 foot driveway. She asked:’ How many of you lived there?’ “Three of us…”, I replied. “well, and the servants”. Her eyes widened. Her mouth moved but no sound came out. “You’re…you’re bourgeois!” she eventually exclaimed. Oh yes. I am definitely bourgeois.

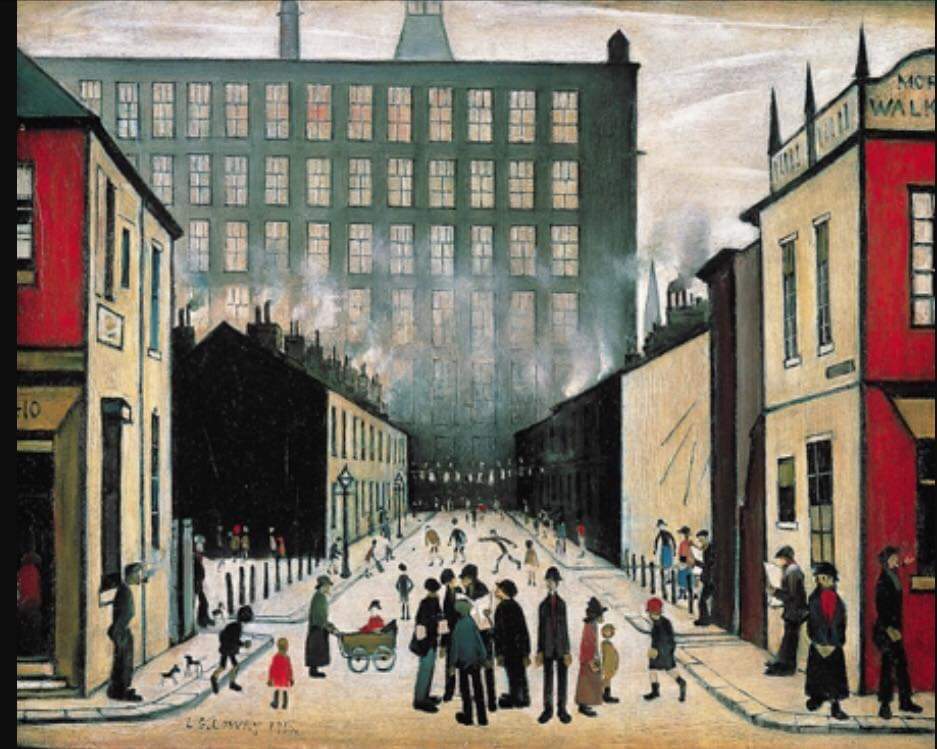

For a Soviet girl, raised as a Young Pioneer under the gaze of Comrade Lenin, it was a crime to have so few people living in such a big house. ‘Your house would have been partitioned – a bit like India (well, it was marginally smaller than India). Every room would have had a whole family in it and everyone would have shared the kitchen.’ This sounded more like the home my great grandparents might have had before they escaped the slums. Their hard work has made it possible for us not to have to share rooms. This didn’t wash with Tanya, and only added to her suspicion of my counter-revolutionary tendencies. A suspicion confirmed when I took her and our daughter – half Soviet, half capitalist – to visit the family’s dirty little secret: our dark, Satanic Mill in industrial Batley.

Yes. We were mill owners. Owners of Victoria Mills. Two generations ago our family had moved away from the valley where the mills were. The advent of the motor car enabled that, as it was no longer necessary to live up the hill overlooking the place of work. The Keans moved north of Leeds. To clean air and fields and big ‘ouses. They sent their children to public schools. They cowered outside the gates in their Bentleys, their children ashamed to be seen in the company of people ‘oo ‘ad flat vowels and d’int speak proper. And bit b’ bit, generation by generation, we became posh. Posh enough to live in a Manor House – even if it was only a semi-detached one. But the money still got made in t’mill.

Batley is a grimey place. In the Churchyard up on the hill top overlooking the mill, the gravestone of my great grandfather stands sandstone black with the pollution of the years. It nestles among the long, unkempt grass, stiff, like the Victorian values of the gentleman that lies beneath it.

We toured the Mill down in the valley beneath. Nowadays it is a Habitat and Heals store. When I used to work there – cleaning the directors’ cars – it was a noisy working mill, making shoddy, the poor grade woollen yarn that makes blankets and army uniforms. Tanya also comes from a textile area of Russia and studied textiles as part of her economics degree. Here we were – the workers’ heroine in the red corner and the son of a son of a son of a son who was the fourth generation of an ‘exploitative’ mill owning dynasty. The proletariat versus the bourgeoisie. What does that make the fruit of our loins? We visited the cafe and our daughter sat, unbidden, at the head of the table. Imperious. I think she knows which side her bread’s buttered on. I’m not sure she’s a worker.

My childhood of the seventies. No hanging out at McDonald’s. No The Clash. Or The Jam. Just bands without definite articles: Pink Floyd, Genesis and records of Beyond the fringe and Pete and Dud. Stone school corridors, cricket, football, tennis and rugby. My parents giving dinner parties where everyone came dressed in black tie or cocktail dresses. (Dad looked lovely in his evening gown.) After dinner, the men went to the drawing room to discuss business and world affairs. I do not know what the women talked about. I do know that none of them had jobs.

In winter, I went down the field and shot things. In summer, we played or watched tennis, went to friends’ houses to swim in their pools or rode our bikes around the country lanes. When we moved in to our semi-detached Manor house, I remember putting my arms out wide and spinning around on the wooden floor of the hallway, looking up to the corniced ceiling of the upstairs floor some fifty feet above me saying: “I feel like a King!”. I did. I do. It was a privilege to live in such grandeur. It feels like a bygone age. Above our home, up in the sky, was a military air corridor. Throughout my childhood, Vulcan bombers screamed overhead on manoeuvres, practising for the confrontation with a USSR that clearly meant to take all this away from us. And now it has. Not by force. But with love. And now it is a different world.

товарищ Kean and товарищ женского пола Khandurova

Lord Kean, Rt. Hon Steven Kean, Lady Kean