I returned to Knightsbridge to report the bad news. The road from Luton to London was just under an hour’s drive. The Vauxhall client had rejected the film script for the commercial to advertise the new flagship model, the Calibra, and I had the duration of the journey to work out how I would break the news to Alan Waldie, one of the most respected and awarded creatives in the industry, whose script it was.

The car had been dismissed by the enfant terrible of the motoring journalist world, as

A Cavalier in a party frock

Jeremy Clarkson

and the car’s makers were still wincing from this insult. Our script had been dismissed as too expensive and instead, the client had instructed me to go back and convince the creative team to use stock footage. Something the Vauxhall team had shot for the press launch – the usual stuff: pristine red car, swooping helicopter shots lovingly caressing the curves of the metal as they wound their way down the Corniche in a cavalcade of twists and turns which showed off every angle to best advantage.

What’s wrong with that, I hear you ask?

Stock footage is pre-existing film of something, where the word ‘stock’ is the operative word. Standard. Unexceptional. Used so regularly used as to be automatic or hackneyed. As an ingenu account man, I had not twigged the horror that I was about to unleash back in my offices when I returned with such an instruction. But the reckoning was coming.

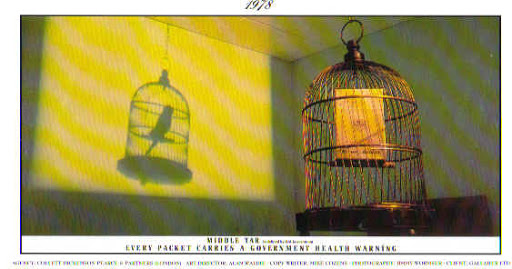

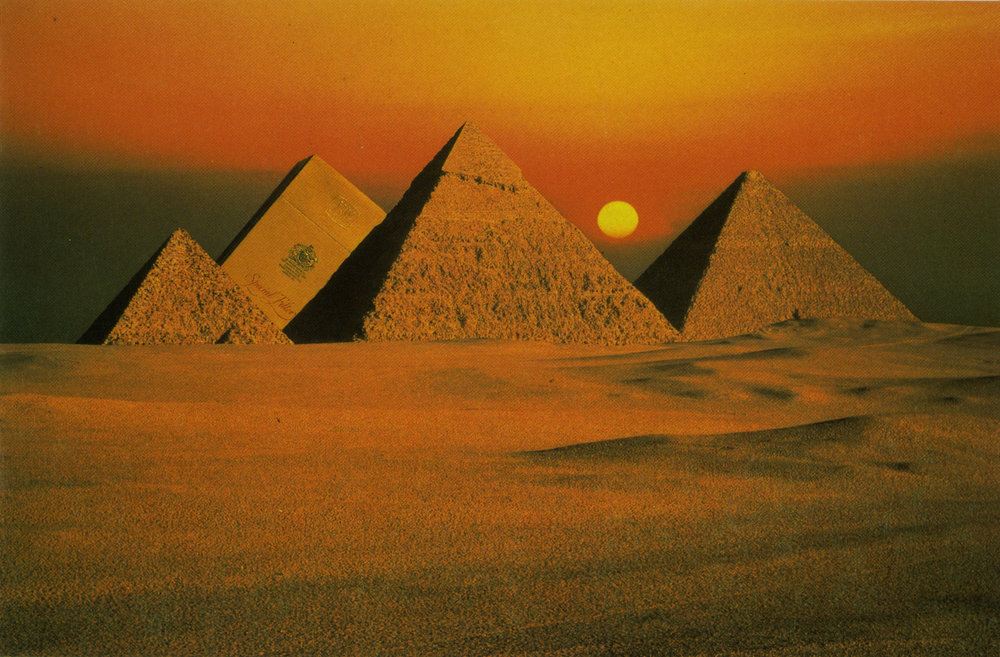

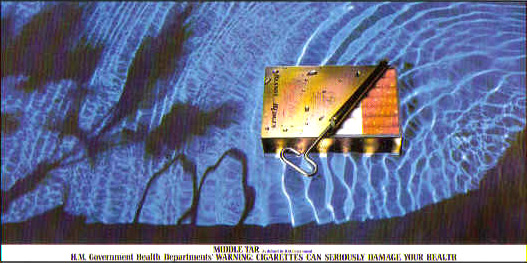

I knocked on Waldie’s door. It was open but still, some respect should be shown to the man who brought the world the Benson & Hedges Surreal campaign from the 1970s. Alan was in his trademark navy blue cashmere sweater and affably invited me in. I couldn’t see any point in soft soaping him and blurted out the failure of my mission. Waldie looked unfazed. Then I passed on the client’s instruction: to use stock footage.

Waldie stood up, walked towards me, reached behind me and closed the door. He sat back down. For the next hour – hour – he gave me a quietly delivered lecture on the sins of stock footage. On the sins of stock anything. He explained, eruditely and politely, why, on no account, could we allow any client to commit such a crime. He decried imagery which turned off the consumer because they had seen it so many times before. He even guessed the sort of imagery the client had suggested might be appropriate (twisting road bends in the South of France, red car, aerial shots lovingly caressing every…etc.). On and on it went, my lesson on the cardinal sin of cliché. By the end, I was fortified with all the arguments and felt emboldened enough to return to the fray with my client. On my watch, there would be only originality allowed. On my watch, from now on, we would do battle for braveness not for the lazy, easy way out.

I never forgot the kindness Alan showed in educating me. It was painful for him but such was his love of the craft that he had made it his mission to evangelise in the cause of creativity. I never forgot his teaching and I wince now whenever I hear anyone talking about using ‘stock’ imagery. It makes me shudder. Such was the power of Waldie’s homily.

When you have been reared in the rarified world of advertising and have learnt to value the brilliance of the persuasive arts at their best, you notice things which fall short of those standards. You notice – and you care – when dialogue is unrealistic, when scenarios are contrived, when you feel you have seen it all before. You yearn for the fresh, the daring and the original. You admire the ones prepared to take risks in the pursuit of telling a story in a way that has not been done before. Who smuggle their message with wit not bludgeon the viewer to death with a barrage of visual clichés and self-serving corporate puffery.

You see this stuff all over the place now, but recently, one particular example caught my eye. Remakes are troublesome at the best of times. It is rare that any film with the suffix ‘2’ is as good as the original. There are some notable exceptions – fans of Godfather II, I hear you – but, as a rule, second, third and fourth times outs feel like pale retreads of the glory of that first film. In this instance, the original eight minute film was a 1976 cult classic by Claude Lelouch, called C’etait un rendez-vous.

The film depicts a fast drive through the streets of Paris very early one morning as the driver, races to meet his lover on the steps of the Sacre Coeur. There is no dialogue, just the soundtrack of a Ferrari engine (though the car doing the actual racing was a Mercedes) dubbed over the film. As Lelouch – for he was at the wheel – steers the car around real life obstacles and through scores of red lights on his speedy journey to the liaison, the single take from the camera mounted on the bumper of his car creates a palpable sense of speed and danger. It is a ride. And you are left breathless with admiration at the feat.

The film was shot with restrictions. It had to be done in one take. It had to be done in the early morning dawn light. It had to take the risk of running red lights – they couldn’t control the phasing of traffic or alert the authorities to what they were going to do. They couldn’t legislate for the unexpected – everything had to be a real reaction in real time.

The film achieved notoriety. Lelouch broke many rules of the road and multiple traffic laws in that one take. The route is full of genuine hazard. He could have been killed. Other drivers could have been killed. The simplicity of the idea and the boldness of the execution are characteristic of the original piece of communication that Alan Waldie was telling me about in his masterclass. The soundtrack added even more excitement to an already lethal concoction.

It would be impossible to make C’etait un rendez-vous 2. You could never replicate that danger. You could never get away with that stunt in a major world city. You could never either replicate the atmosphere of that film nor the impact. And yet, Ferrari chose to do just that. And if any brand has the balls to take on such a task, this stable has the pedigree.

You can see the temptation. A version of the film for the modern era. A daring reminder of the ferocious excitement of a Ferrari. An iconic event for an iconic brand. A reminder that Ferrari cannot be rivalled for audacity, thrill and speed. The plans were put in place. The logistics. The location. The cast. The storyline. The hype began.

When the remake was launched, it fell, stillborn into the internet. The film was panned by everyone, even the people who made it. Why? Timidity. Fear. What ended up in the can was a stream of visual clichés stitched together by a C list celebrity cast and a paper thin, wholly incredible plot line. In trying to make a clever piece of communication, they produced an embarrassment. A Formula One hero driving around a completely benign Monaco bereft of any other traffic or hazard and a very pretty florist who he takes for a circular ride of the race circuit in the car (and, maybe beyond, off camera, we are left to infer).

But the really excruciating part of this Grimaldi hagiography is when a Covid-compliantly masked Prince Albert climbs into the Ferrari to enjoy a jaunt around his Monégasque estate with his racing driver chauffeur. As Private Eye used to say: Pass the sick bag, Alice.

What is so horrendous about this pastiche is how it took a brave and original idea and completely neutered it. Every ounce of risk was extracted surgically. All the pace, all the sense of racing against time were removed. Why? Because there were no constraints. None on budget. None on traffic. None on the driver. None on when and how they could shoot it. They could have as many takes as they liked. As with so many creative endeavours, total freedom creates a mess. Constraint can create the clever and produce the unique, because they harness a moment and force you to think. Here was a film with no thought in it at all (or too much interference by too many people).

What was left was a jaunt around the Monaco circuit with a minor royal. Albert’s appearance was an example of the client asking to make an appearance in the commercial – presumably in lieu of paying for closing the streets of the Principality – so it served no one, not even him. In fact, it made him look vain and pathetic. And it probably damaged Ferrari, too. Ferrari is fearless, sexy and un-ignorable. This promo film was anodyne and stupefyingly dull. Not core values of the world’s premier automotive marque.

Waldie would be chuckling. “See?”, he would have said. “See what I mean? Stock footage isn’t even original when it’s shot. It’s just lazy, bland, platitudinous – bereft of any thought or imagination, like an oven-ready meal. Bromide for the eyeballs. It changes no perceptions, it doesn’t get the blood racing, it numbs the senses. It has no life.” True creativity has to be fought hard for. The easy thing to do is actually the most risky because it risks being ignored. Vive 1976 and C’etait un rendez-vous. Bold, arresting, fresh and exciting. Just like all the best creativity that has ever been. Imitators beware.